Artist Indira Ardolic has seen her fair share of unscripted activity on-stage. As one of the rising talents of NYC’s live-coding scene she puts their programming work in front of audiences as part of the performance. Foibles and miscues are just part of the routine. Ardolic once had a performance stall for more than 10 minutes on stage after a program stalled and she resorted to drawing in MS Paint to wait out the error. “I just kind of leaned into it,” she said.

But the danger of live performance also generates unexpected joy and delight. Ardolic was playing a DIY performance recently and had created a spider as a “main character” with a procedurally animated walk. The crowd loved it. “Everyone chanted ‘SPIDER SPIDER SPIDER,” she told me. “Is it because it’s a DIY show or because I have so many friends here?”

Earlier this year, I profiled Roxanne Harris, another live coder with a background in jazz saxophone. Harris' relationship to video games is more conceptual—game design's interdisciplinary nature mirrors her own syncretic practice. For Ardolic, the connection is more literal: she's using Unreal Engine to bring software designed for game development directly into spontaneous, ephemeral visual experiences that exist only in the moment of performance–she’s using Unreal as a creative technologist to bring software designed for game development directly into spontaneous, ephemeral visual experiences that exist only in the moment of performance.

From competitive play of esports to live-streaming games on Twitch, games have been experimenting with live performance of digital work for quite some time. These displays demand that we think about the performer, the player, and the participants on exactly the same level. But for the relatively newer popularity of live-coding concerts in the last 15 years, game engines are fertile territory to explore for Ardolic and others.

“I’m a Staten Island truther,” Ardolic joked when I asked her about her upbringing. The borough is physically and culturally distinct from the rest of New York City, largely due to its status as the least-populated borough. “I was close to the park,” she said. “There are foxes and deer, but not enough local art.”

Games were a close part of her childhood, but making music was not. She said she learned to read from Final Fantasy 8 since it had no voice acting, and her mother showed her a Final Fantasy anime music video when she was young. After enrolling at NYU Tandon School of Engineering, one of the oldest programs in the country, she came across a group of students at the school’s Game Innovation Lab sparring about the stress of coding in front of others. “It's all well and good to want to build the next real estate app for an enterprise software company,” she said. “But when I met this group of artists I was like you can just break code as a performance?” Soon, she was an active member of LiveCode.NYC and putting together shows around the city.

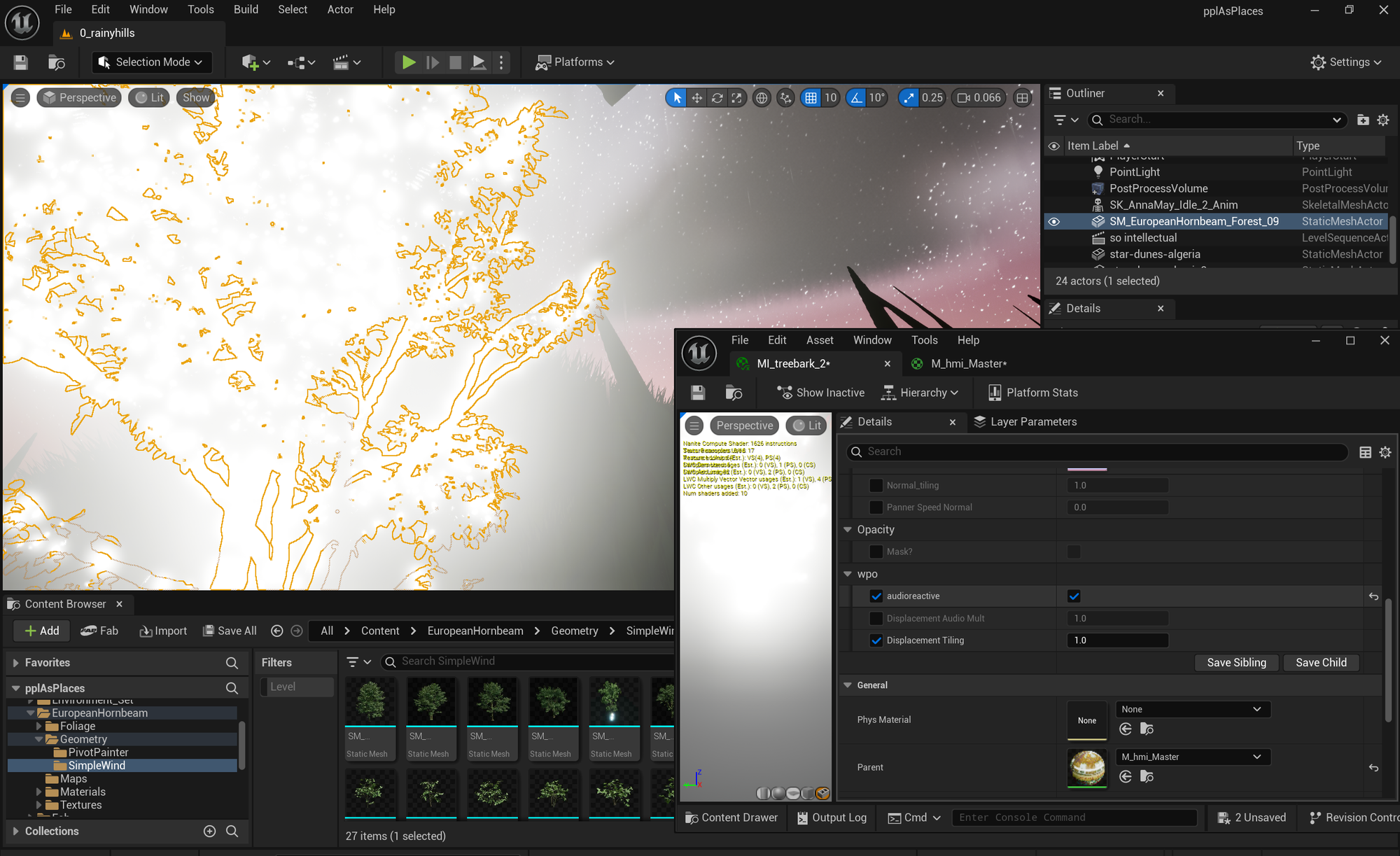

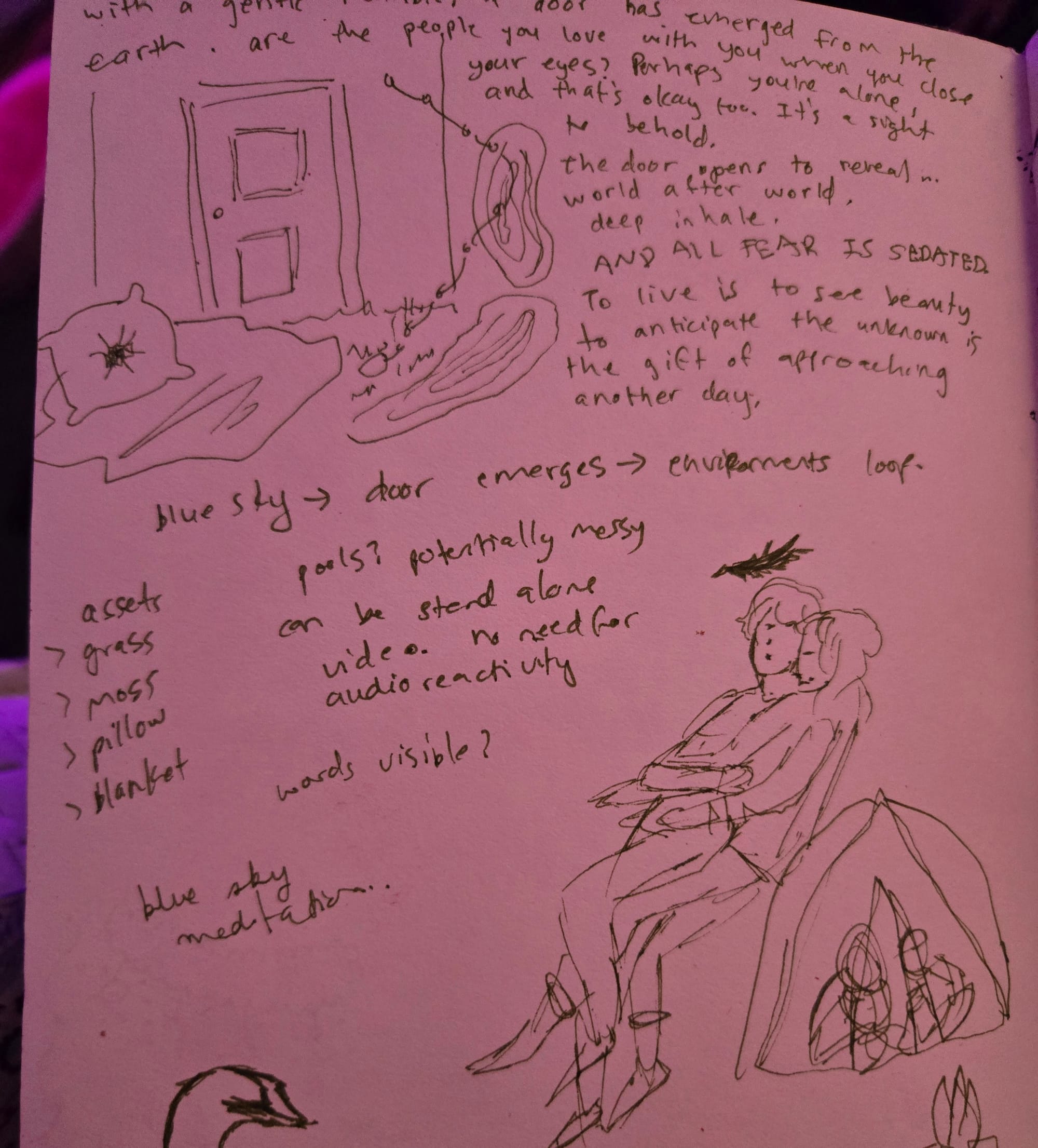

The love of games as spaces for imagination led Ardolic to Unreal Engine, her primary canvas for creating audio-reactive environments from her audio input. “Initially, it was the thing that made the most sense to focus on the visuals,” she said. “It helped me replicate those more quickly than other software.” Ardolic then takes sketches and photos to guide her approach and downloads 3D assets for each performance. Sound input controls all of the visual parameters, adjust the color, shininess, and texture and make the objects stretch, ripple and morph during the performance. While working with experiential designer Erin Wajufos on a collaborative project, the two played with visuals from the underwater adventure game Subnautica—its bioluminescent creatures and alien depths became raw material for their real-time environments. "Erin was obsessed," Ardolic said.

Ardolic says that her synesthesia–a neurological condition where one might see colors or taste words–plays heavily into her process before a show. “I can close my eyes, and see a scene unfolding,” she said. Games provide a unique outlet as a vessel for both audio and visual expression. “if you can replicate what you're feeling or seeing, it's just makes you feel good to look at it,” she reflected.

At deeper level, though, Ardolic argues that working in game engines brings her closer to the heart of real-time performance. Game design is an iterative process that requires designers to let their mistakes shine during the process of play-testing. All of the miscues and bugs become the raw material for meaningful interactions in play. Ardolic points to the intentional and unintentional mishaps in Insomniac Games’ work such as the many flight glitches in Spryo to the secret behind-the-scenes museums of unfinished content in the Ratchet and Clank series. “Sometimes when things break, that's an opportunity to embrace it,” she noted. “That's what I like about 3D things.”

While games and live-code audiences might be forgiving, New York is not. Ardolic is still working through an MFA at Hunter College and feels like there’s pressure for artists to be “driven towards this perfectionist route.” For Ardolic, that’s in sharp contrast to what she’s been seeing in live-code communities in other places like Sheffield and Barcelona.

For now, she dreams of bringing the swirling, ethereal mass of the "astral plane" from her favorite manga Berserk into existence—an environment where the landscape shifts endlessly. "It would look so beautiful," she says. The only obstacle? "My sad, beautiful dying computer. The hardware is sometimes my least favorite part of the art form."