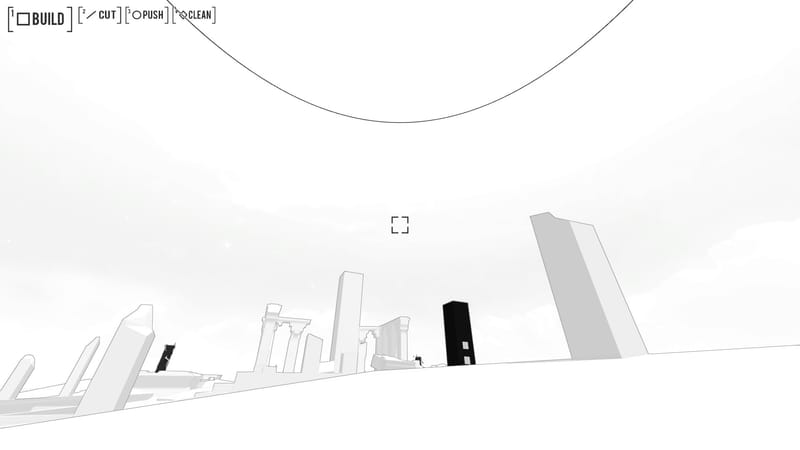

What happens when a designer privileges feeling over function? Mario von Rickenbach's practice does just this. Moving from architecture to interactive design, the Zurich-based creator builds games that prioritize sensation and spatial thinking over conventional challenge structures.

Here, we focus on the re-release of his 2012 game Rakete to demonstratechanged something and how quickly meaningful interaction can emerge when physics feels right. Rather than extensive testing or market research, Mario trusts his intuition about how objects should behave in digital space—a sensibility shaped by his architectural training and collaborative work with filmmaker Michael Frei.

His games speak the language of digital kinesthetia, creating the tactile quality of movement that matters more than points or progression. We speak with Mario about the value of rapid prototyping, why architectural thinking serves interactive design, and how cooperation becomes legible through the weight of virtual objects.

Jamin: Going back, can you tell me about how Rakete fits into your evolution as a game designer? You're re-releasing it, but it was also released 13 odd years ago, and your practice has grown and changed a lot over the years. Where does this game sit in your evolution as a game maker?

Mario: When I think about it, it's quite a unique project because it's the only project that I've ever done that was made quickly. The game was made in one day.

Jamin: Mhm.

Mario: There was an event competition called Experimental Gameplay Competition, and they made these online calls. However, there was one with a live event in Berlin where they said we need a playable game with five buttons. Just send something if you have something. I thought okay, I will not spend much time on this. I had wanted to make a game with a lot of people together, like 100 people together, trying to fly an airplane.

But since I had no time, I just did the simplest thing I could imagine. If I remember correctly, I started in the afternoon, and in the evening, I showed it to my flatmate to test. It didn't work so well. The next morning, I changed something and made 28 levels in half an hour. I thought, okay, it just has to be done. I don't want to spend more time on it. I even made sounds with an iPad app very quickly—it was all basically done without any testing. I just made the game, finished it, sent it, and that's it. Of course, I tested it myself to see if I could play it, but I hadn't tested it with others.

It's very unusual that I just sent something untested and unfinished. The title shows how simple this is.

Jamin: How is it pronounced?

Mario: It’s the German word for rocket. Rakete. And the game was being shown in Germany, so it seemed to work.

Jamin: One of the strange things about English is it's not consistent. When new words are introduced, they don't carry the origin with them. For American English speakers, we don't try to pronounce French words with a French accent versus Spanish—my Spanish is not bad—but with Spanish, everything is consistent. Even words from other languages, the pronunciation is consistent regardless of the origin of the word. But English is a bit of a mongrel, just a mix of different pronunciations.

Mario: I find it cute when people just try to say it in some way and it sounds different but you get what it should be.

Jamin: Yeah. Rock-et. Rakit.

Mario: Rakete.

I was not actually there at the event when they showed it. A little bit later, two weeks or so later, people told me that it works very well. Actually, I haven't tested the game. I haven't even seen it, but people said to me that it worked well. It won a prize.

Jamin: You mentioned that the game was done quickly. Since then, your process has been more deliberate in terms of concepting and design. Tell me about your process or how it's changed over the years from this specific project that was done very quickly.

Mario: I'm usually much more explorative in trying to find ideas. So it's not that I have an obvious idea from the beginning, but more a thing that I want to—that I could imagine could be interesting to explore, and then I will try different things around that. Maybe I have some interaction in mind, but usually it's more that I try to find an idea by trying things, and not that I want to finish a project in one week or a short time.

Jamin: Well, there's also, as your creative profession develops and you have a body of work behind you, there's quite a bit of pressure on releasing things publicly. And it's very hard with games also because you can do all kinds of internal play testing or prototyping, but it's very different when things go out and live in the real world.

And so, as a designer, there's this tension between wanting to get public feedback very quickly, but that is in conflict with your reputation—you can't just release things every week unless that is your design practice, like I'm going to release things. And there's no correlation between whether or not something is done quickly and whether it's good.

Mario: Right

Jamin: You have a background in architecture. Is that right?

Mario: Yeah, I started studying architecture, and it was great—just a year—I liked the idea of designing things that are used by people. But what I didn't like is that it's so abstract. You cannot actually test what you're doing. You cannot try things.

Game design at the art school here in Zurich was a new thing they introduced. I didn’t have to plan so much. I could try things and see if they work. It's more interactive, the process itself. That really fits the way I work much better.

I don't start with this very refined plan of what to do, but I really have to see what I'm working on to understand if it could be interesting or not to continue.

Jamin: Yeah. I like games played by people with architecture backgrounds. Games pull from the spatial thinking that's required in architecture and some of the conceptual design, the framing of the work in 3D environments. But yeah, like you're saying, the benefit is that people can play it, whereas the timeline for architecture projects is exceptionally long. So many parties are involved in getting something into the built environment. Games allow you to scratch that itch of wanting to design for other people, but be able to do so quickly.

Jamin: When did you meet [filmmaker] Michael Frei? Was that before or after—was he involved in your life before Rakete?

Mario: After that. I don't remember exactly, but in 2013, like one year later, he contacted me because he had this short film [PLUG & PLAY] he made and wanted to make a game out of it. He tried to find someone who works with interactive media and games to create a project. He had some idea how to do it, but he didn't know how to actually get it done.

We haven't seen each other before, but some people recommended that he get in touch with me for some reason. When we met first, we understood that we have very similar interests in terms of what we like about games and what we don't like about games. It was completely interesting to meet somebody from even a different field, but then you talk and you have the same references, the same things that you think are great, and nobody knows them.

Jamin: Yeah. I hypothesize that games are not real in the way that we have conventionally verticalized them as an industry, and that people express creativity through games. Still, they're coming from another creative design discipline. It could be film or architecture, and then they find their way to games. With people bringing non-game perspectives to games, I can always tell because the work often feels different or abandons particular conventions. I often have a challenge when game makers are only conversant with other people who play games. They couldn't sit down with an animator or a film director and actually talk about what they do. So, I'm not surprised that you and Michael found common ground.

Mario: When I studied, I talked to people who are into games or fans of playing games. It was often hard to be critical about games. It's comforting to know that I'm not the only one who doesn't care about 90 percent of games.

Jamin: Yeah, loving games in spite of themselves vs because of them—you're either attracted to the things that you're seeing in games and so you want to make more of that, or you see through that and see something beyond, see potential. You're quite optimistic that there is something there, even if you can't see it just yet.

Mario: Exactly.

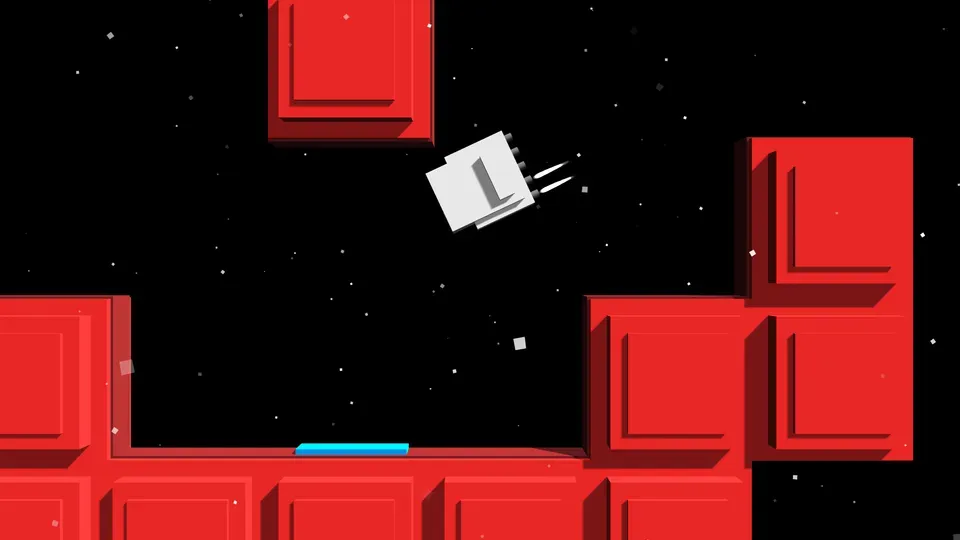

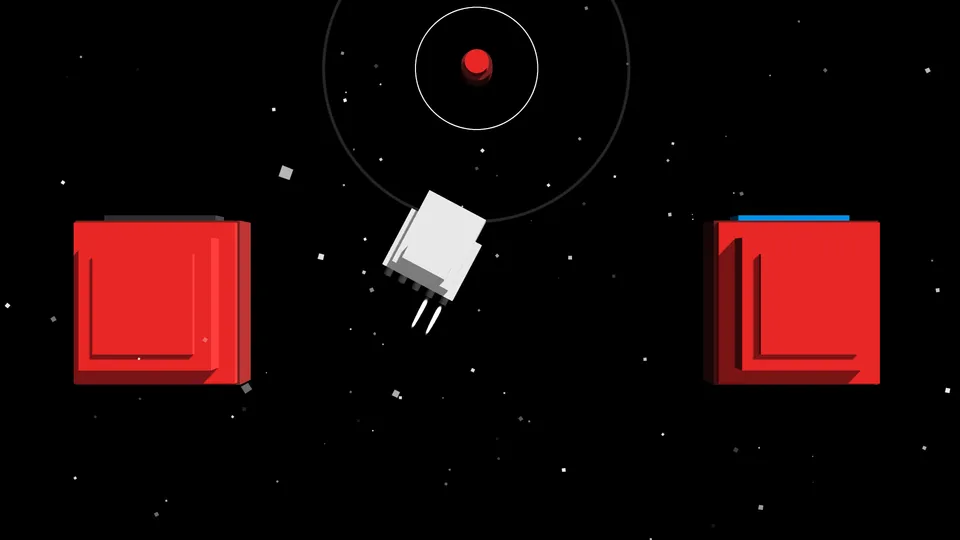

Jamin: With Rakete, the way that cooperation works in that game is just stripped down to controlling thrusters together. I'm curious about the weighting and the physics. How did you think about and design the weighting and movement of the thrusters so that success didn't feel impossible, and it felt like you could do it? The ship moves at a certain speed, rises, and falls. How did you design the physics and the dynamics in the game itself to make cooperation legible to players?

Mario: I didn't know if it's playable when different players actually control the thrusters, but I just played it myself. I wanted to make sure that I could actually play it. So I made it as slow as possible but not annoying. I remember that first, I disabled the gravity because you're in space, right? And then I understood that it doesn't work if you don't have gravity. So I needed some gravity, but not too much.

This really helped—this idea that you're not really in space but somewhere close to some planet. So you have some force that drags you down a little bit, but not too much, so the rocket doesn't get too fast. But in the end, it's very intuitive. Often, when I tweak physics—and I do that all the time—it's really that I know where to start because I have already done something similar. So I know, OK, everything is too fast, I have to slow it down and play with the numbers a bit.

I don't think I spent a lot of time tweaking these forces because it worked, so I guess I just left it. Maybe I was lucky.

Jamin: Maybe. I mean, not just lucky. Looking at your body of work, that sense of how it feels to play something versus what you actually do in the game—I know with animation, so much time is spent around this idea of feeling, trying to create an object onscreen that does not exist in the real world but still behaves or has the characteristics of something real.

So it's not surprising to me that this would be something that you would figure out very quickly—this ineffable kind of feeling. Although you do have to pick values at the end of the day, you are working inside of a game engine, so you do have to make some choices there, but it's not that surprising to me.

Mario: But I mean, these kinds of things that you need to tweak to create physics that work interactively—I think I was always very interested in that. I remember the first time I learned how to write code that makes something move. Before that, I had learned how to program in PHP when I was 15, maybe, to make some websites, and so I didn't know how to move things. So I made a little game where you click, and then it reloads the page, and basically runs by reloading the page.

When I first learned Flash, I could actually move around an object frame by frame with physics. I spent so much time just creating bouncy balls that have some physics, some drag and some wind, and some attraction with the mouse and collisions—all these things that are super simple, but together they create this dynamic.

It's comforting to know that I'm not the only one who doesn't care about 90 percent of the games.

I really spent a lot of time making little experiments. When you play around with these kinds of things, you get an idea of what you need to change to slow something down so there is more control, or create a more dynamic range of movement. It's not so one-dimensional because you know what these numbers mean and how they change the movement. So there are many things you could change about this system. But if you know exactly what you want to achieve, it's very important to understand how it works.

Jamin: Audiences don't really understand or they're not interrogating or asking questions about how something feels, and that's hard to put into words. So as a designer, I think you are much more acute—oh, if I change this value to this, it feels like this. But as a player, you only get the finished thing. And people try—it's tough to describe something that is proprioceptive, that you're trying to tell something about how an object behaves.

And because games are interactive and because players put time and effort and thought into how they want to control the thing, I think sometimes it can be tough to put that feeling into words, and so you end up with things like "gameplay" as kind of a catch-all—oh, I like the gameplay—to describe everything that's happening in the system, whereas you're looking at it in a much more limited frame and say, oh, these are the things that I think make for a pleasing outcome or what I'm trying to explore with this particular work. So there is a challenge of language, I think, for designers to talk about what it is that they do—it’s much harder.

Mario: Yeah. See, when you see new tools that are easy to use, some things are super easy to do—like if you talk about Roblox, they have multiplayer physics. It's just there. And if you ever tried to do that outside of this well-made engine, it's hard to do. So I think there are also these kinds of expectations that some things just work.

Jamin: Yeah.

Mario: And also, for example, when I made Rakete, the physics was just there. That's why I could do it so quickly. So maybe five years earlier, making this game would have been quite challenging.

Jamin: Very hard. Yeah.

Mario: So for me it was really like, OK, you have Unity, you start, you have some blocks.

Jamin: Yeah.

Mario: So I guess it's more about still understanding how they work. So you still need to know what you're doing, but you don't need to know all the details all the time because you can use them more easily.

Jamin: Yeah. I mean, you know, I—this is a hope that I'd had with games. I guess, you know, that they are very much tied to technology. It's a medium that is very tied to its form of creative technology. And you do see this in the arts in other places, you know, the advent of the Kodak Brownie handheld camera, camcorder, or iPhone allows people to create without requiring specialized training. You can just point and shoot, or you know, you can basically start using cameras. Then you start to see more experimental expressions of that medium because more people can play with it.

Since Rakete, how much do you accept the tools, the presets, and the conditions of the tools that you're working with? Are you still going in and trying to fix things, or have you moved on to other ways of thinking about interaction design?

Mario: Yeah, I do both. It depends a bit on whether I have to finish something, or if I have to get some work done, or if I explore something. So I like to build my little tools, especially with physics. So I often make some little physics parts—not really engines, maybe, but little things that do certain things in code, maybe more in a simple way, but I have complete control over them, or perhaps some other kinds of things that are hard to do with the built-in tools. Ultimately, I often try to combine these different things to use the best parts for each job.

Mario:. I still use a game engine. It's just the reasonable thing to do for my kind of work. Games that have very different mechanics or things that work differently, and they're all kind of together in one game—for that, it's very good to have some simple tools and not need to reinvent the wheel every time.

But for people who have more mechanics-based games that have a very consistent mechanic throughout the game, it may be easier to do your own thing because you always have some internal structure that is very clear. I often—not always—try to do something more consistent. I'm now finishing Pocket Boss, a collection of different little interactions and games, and they all work a bit differently. I could not imagine doing something like that without the game engine because I often use one tool just for one scene. So it wouldn't be worth it to create your own thing to use it for 10 seconds of your game. It’d be super inefficient. For my game, they wouldn’t exist without game engines.

Jamin: Yeah, that's a good point. It does make me appreciate games that have a real minigame structure to them. You know, WarioWare, Mario Party, or those types of things, where you have these little snippets of a thing—these short little snippets of a thing. And yeah, that's not possible—that's more possible now with game engines than in the past. You'd need a huge team; each little piece is designed by hand and whatnot, so I can see that as a real challenge.

One thing I did want to ask about with Rakete because looking at your body of work, you haven't really done multiplayer games—that wasn't something that grew out of your creative output, out of your practice. And I was curious why. Was it just the prompt, or is there an interest? Do you prefer games that are individual experiences?

"If you know exactly what you want to achieve, it's very important to understand how it works."

Mario: No, before that, I once—maybe in a similar situation—I made a game called Straight No Chaser. It's a two-player game and it was also with a similar setup. There was an event, a games exhibition, and there was a bar, and at the bar they said it would be nice to have two joysticks—these eight-way joysticks like the old school ones.

When I made Rakete, I knew it's relatively quick to make a multiplayer game because having multiple players already gives you so much randomness, making it interesting. You don't need to have a complicated game.

I don't know why I didn't do more after that. One reason is that it's hard to find people playing it. It's harder to justify spending a lot of time developing a local multiplayer game if you don't have a clear goal for where to show it. That could be more a practical reason, but I like the idea of having people play together.

Jamin: Yeah, there's an emergent quality to multiplayer games that is very difficult to plan and design for. You can only give a context, and it's tough to predict how players will react or how they'll approach particular challenges together. Obviously, the more people that get involved, the greater the potential emergence that happens. But building a system that is easy enough for people to step in and understand what is happening very quickly is very hard.

I think there's certainly a crisis here in the United States in terms of people spending time together, and I do wonder if local multiplayer games are a way out, or the fact that there are so few of those contexts to play local multiplayer games because there are no arcades and all the games happen online. Although I guess you do see quite a few because of Twitch, quite a few online multiplayer games have become quite popular over the last couple of years, such as Content Warning and Phasmophobia.

Enjoy this conversation with Mario? Consider supporting Killscreen for the year for more essays, interviews, and profiles on the future of interdisciplinary play.

Mario: Personally, I don't really play online multiplayer games, but I like to play local multiplayer games sometimes.

Jamin: On that question about multiplayer, you know, the new release of Rakete has a solo player option. That's what I did. Do you feel like there's something gained, something lost in allowing people to play by themselves versus forcing them to find another person to play with? Because you could have shipped it as if it's a requirement — you have to find another, it's a two-controller game, or something like that.

Mario: Yeah. No, I think I noticed that people also like to play it by themselves, so it's kind of OK. And of course, it's a relatively conventional game if you play it alone. It's fun. You can play it. But the real thing is that if you play it together.

Jamin: Well the last question for you was about your relationship to contemporary art and gallery contexts. One thing that is very interesting about your portfolio is when you list the description of the game, you list your awards and recognitions, but then you've made a point of documenting all the exhibitions and showcases.

And that looks much more like someone working in a contemporary art context as opposed to someone who's just making games. It's rare that I see that from someone who designed games to be able to document all the places that your work has shown. How do you think about physical contexts at the beginning of your process?

Mario: Yeah, I don't usually think about it. I mean with some exceptions.

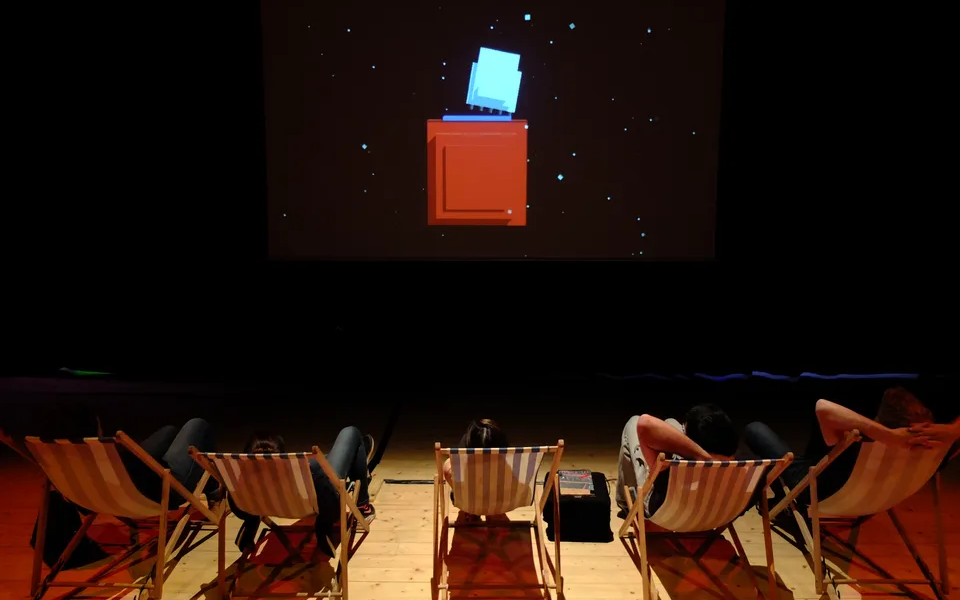

When we worked on Kids that was also intended to be shown at exhibitions, but I think otherwise it's really not something I would think about first, because I think it doesn't matter. I'm not trying to be as close as possible to art museums or things like that. But it is a nice place to show games because it will hopefully reach some people who would never play otherwise.

So you really have very different feedback when you see people seeing a game—I mean, we had a lot of exhibitions with Kids, and then depending on when you show it online, you see some responses like what the fuck? And you show the same exact scene in an art museum and people are super serious about it like Hmmm, what's the meaning behind this?

Online people really don't care about you and why you made that. It just exists as this thing that is somewhere online. In an exhibition context, it's much more important who made it and that it's a kind of cultural product.

Jamin Warren: Maybe that is one of the benefits of being someone outside of a contemporary art context who has work that shows, and you have access to an audience that you're not thinking of with a gallerist in mind. And so that gives you the freedom to think about what players want, and the context matters, but is not as crucial to your process. Whereas for someone looking to show work in a contemporary art context, they're often doing it for collectors, or just some of the financial realities of what it means to be a modern artist mean that you're bound to that system. You have to think about what's going to show well, what's going to attract attention, and for you that is incidental to your process. And that's probably a good thing.

Mario von Rickenbach: Yeah. I think I mean I do the thing that most people in games always tell each other to not do—I make things that I would be interested to see myself. Maybe I'm not good at trying to see the market or see what a gallerist wants, but I know what I would be interested in.

That's the thing I'm sure about.

This interview was edited for style and grammar.