When I first enter the Hammer to view Lawrence Lek's Nox High-Rise, I am blinded.

Flanked on either entrance by two disembodied head lamps, the expansive entry way obscures the way I came but points a way forward. A large projection screen with the initial video work introducing me to the "CGI noir" world of NOX.

London-based artist Lawrence Lek is one of my favorite artists working with game engines today. With work spanning filmmaking, video games, and electronic music, he has made his mark exploring the concept of Sinofuturism, China's relationship with the world in a post-AI future.

What is particularly remarkable has been Lek's focus on the near future and an astounding prescient instinct. He has been exploring our contemporary questions about AI in a pre-ChatGPT world and what comes after self-driving cars entirely replace human ones.

In this conversation, Lek and I talk through his childhood, why horses make good companions, and what to do when AI gets depressed.

Jamin: What was your relationship to sci-fi in Singapore and Hong Kong while growing up? What was it like to see those cities in various degrees of architectural and cultural flux, and how might that have impacted your thinking about the future?

Lawrence: Once you have these environments like Singapore, Hong Kong, or Japanese cities that are shorthand for the future, but you actually live there, it's a weird thing—seeing where you live and then seeing where you live represented. For example, in LA, you get that quite a lot. There's LA in the movies or the entertainment industry, and LA as the urban texture. It's like two completely different universes.

When I was growing up, there wasn’t a massive disconnect between high-rise/low-life kind of thing, because in Asian metropolises, you get everything. Growing up in Hong Kong, Singapore, and Tokyo, these are the paradigms of nineties cyber-futurism.

AIDOL is a feature-length science fiction musical that tells the story of a fading superstar, Diva. It recruits an aspiring AI songwriter to stage a comeback performance at the 2065 eSports Olympic finale.

Sometimes, the illusion of a place and how it's represented really align with each other, like environments in science fiction and cities. And other times, there's the place where technology happens, and it looks nothing like the product. No scientific innovation or speculation often needs to happen when it comes to urban environments. In a direct way, when land values are compressed, people build up, like in Hong Kong or Singapore, versus sprawling out in America.

Later, I started thinking about how those places were built with many multinational investments. All the Marshall Plan-type investments in these countries also drove a lot of that international infrastructure and the look of the cities. This complex interplay of so many different factors with projects like NOX is about weaving deep levels of world-building that might not just be visual, but are tied into the narrative and other different flows inside the work.

I lived in Chinatown right after college, really in the middle of Doyers Street, which is right in the middle of Chinatown. If you light it in a particular way and catch the neon signs in a particular way, that's gonna present a specific look and feel. My experience was just seeing a lot of people going to work. But primarily for me, not being Chinese, there's this sense that this is not a place for me culturally.

J.G. Ballard also spent his childhood as a colonial expat kid in Shanghai, and he wrote about it in Empire of the Sun. It’s important not to discount those perspectives because they are very much outsider perspectives, which I also feel I have.

Nox High Rise is Lek's first solo show at the Hammer Museum in LA and builds on work developed for the LAS Art Foundation. The second in a three-part trilogy in the titular world Nox (short for "Nonhuman Excellence), High Rise follows a self-driving car that begins to wonder about its place and its future. A conversation with the company's AI therapist sends it to a equine therapy session and asks questions about self-care if there is no self to care for.

Lawrence: My first trilogy is the Sinofuturist trilogy, which looks at the 40-year distant future and the rise and awakening of AI as this protagonist, because they wouldn't have to pay fractionally per token.

The first episode in the Smart City series was Black Cloud in 2021 for the Hyundai VH award. That was about a surveillance system that gets depressed, and they talk to their built-in psychologist. Because I thought that's what a big AI company would do to treat its non-human workers better. It's like a Friday massage, but for AI. It's also quite affordable. So NOX is the second part of a trilogy.

Jamin: So with NOX, had you always been thinking about building this trilogy together? How much of it is a natural extension of your previous work?

I've always been interested in serial forms of world-making, whether episodic TV shows, science fiction sagas, or video games. There’s this idea of completion of creating a major work–this Wagner opera kind of thing, where you have this vision of having a seven-day-long opera kind of thing. That's really not my vibe.

You're gonna build your own theater.

Exactly, in the forest, maybe floating, maybe off-world. [Laughs]

I have always been much more interested in incremental forms of art practice because I get lost in decision-making if I ever think of a really ambitious project. I'm always oscillating between this grand vision and this tiny bit I can do this week, for this deadline, for this show

The main character of the work for Black Cloud I finished pre-pandemic, around 2020, was that I was thinking of making something set soon. That was two years before ChatGPT, so it's just completely different.

Previous installations of the Nox Universe

Jamin: It was B.C. Before Chat.

Lawrence: Exactly. The subjects around embodiment and AI were becoming more everyday concerns worldwide, looking at present-day ideas about AI and personhood.

But I was also looking at histories of chatbots, particularly Eliza, for Black Cloud. How could you know the difference between having a conversation and feeling like you've been heard? Does that make you feel like you've had a good conversation?

The same program has been expanded into a rehab center for bad self-driving cars in NOX. And in the show, you go on a journey through one of the rehab programs for one of these cars.

Want to read our entire interview with Lawrence? Members can read our whole conversation.

You talk about your work before or after ChatGPT because there is something called low-background steel. This was steel used before the use of the atomic bomb, so it doesn't have any of the attendant radiation from bombs that were dropped after. So if you're trying to build these radiation-detecting machines, it's actually incredibly important. The only place you can find this steel is at the bottom of the ocean, which has not been tampered with by the atomic age.

You've been having these conversations about artificial intelligence before and after ChatGPT. As your career continues, you'll be able to look at what kinds of questions will be marked by this new tool that was influencing as it happened, much like the Atomic Age. You know, one of the things that humans will leave in the geological record is the use of hydrocarbons from fossil fuels. That's it. Everything else will disappear. Every building, everything else will be gone.

From a technological standpoint, your work has these fingerprints of different moments in technological evolution over time, which encourages you to ask different questions.

In 2016, when I had been making virtual worlds for five years already, I imagined each project that I was making would be a snapshot of the available technology at the time, right? It's a slice of whatever programs I'm using, Unity or Unreal, or Processing—low poly, new shaders, new graphics, high fidelity, higher resolution. It's also baked into the work itself, yeah.

Of course, if you're a sculptor, you can sometimes chart how well that sculptor is using the materials they're using. They’re starting with cardboard, then they're doing it in wood, then they're doing it in bronze. Then times are bad. There's a war. And then they start doing things with the cardboard again.

So it’s the same with my projects, because they've ballooned into these 100-gigabyte monsters that I have to divide up. Because the work is about world-building, I always have this long-term continuity.

You're taking advantage of the questions you're asking about your relationship to technology and that the practice itself is enabled by technology. You can dip in, think about an idea, meditate, and then add. It’s a palimpsest where you write on top over a long time.

However, with NOX, the original version in Berlin was more directly interactive. When you went in as a visitor, you got these locative headphones that track your location in a space, and as you move around the physical space, the voiceover gets triggered. It’s a physical version of an open-world game. But that was spread over three floors of a former shopping center.

At the Hammer, I worked with Celeste to condense that multi-floor experience into a single space, but to channel people in a way that’s deliberate but open at the same time. In a video game, you give players the illusion of choice, right? You can go left and right, but it doesn't feel like that.

In Berlin, different videos were shown on other floors. It was basically a walking simulator, except you weren’t actually walking. On the ground floor, there was one day of treatment, and you go upstairs, and it's the next level, and you get the second part of the treatment. In the Hammer, it's condensed into a single space. Because you're in the same acoustic space in the museum, it's in one zone. I thought I'd choreograph the whole thing as a simultaneous, three-channel video installation. The entire space is working like a choreographed loop.

Jamin: Let’s talk about the Hammer show. How did the past experiences of showcasing NOX influence the showing with the Hammer? What were some of the things that you were hoping to do differently?

Lawrence: Sure, so I mean with projects like NOX, that from the outset were meant to be this complementary spatial design and scenography project, because, you know, NOX, it's both the name of the program and the name of this place where it happens. I was thinking about different iterations, bringing both elements together for the original NOX, which I showed at the LAS Art Foundation in Berlin. I worked with the scenographer, Celeste Burlina, who was instrumental in the Hammer show and designed the spatial layout.

From a level design point of view, it's not just the environment. It's also choreography. So you're choreographing a spatial, temporal journey through a place. And sometimes that is as simple as we start here. There's a sign, there's a light, there you go. Sometimes it's super linear.

In an art environment, you can only hope for people who are fully immersed. Sometimes people stay halfway, or they see the whole loop. Some artists are like, No, there's strict entry times. But for me, it depends on the project. It felt more appropriate for NOX to have it be an open world, but with a suggested route.

Jamin: Horses and cars are both objects of locomotion and have this component of care, caregiving, and interiority you're exploring. How did you get interested in cars and horses, and how did you find that the two would intersect with this equine therapy approach in NOX?

Lawrence: Doing something around cars was almost accidental. In 2018, I was invited to do a show in London at Bold Tendencies, a public art institution in a rooftop car park. I was like, wouldn't it be weird if this car park was turned into this self-driving car learning garage? This was back when Waymo wasn't a thing on the city streets.

A couple of years later, when I was thinking up ideas for this depressed AI—the smart city surveillance system in Black Cloud—I thought it would get alienated because they're super intelligent but actually crave some kind of embodiment. So in Black Cloud, the surveillance system sees this fox in the city, and they're like, I want to be like that fox. I can never be wild and free like that fox. But maybe I can imagine what it's like. You get that subjectivity in video games—I could perhaps role-play as the fox.

So I thought, OK, what is the next counterpart of that? In Black Cloud, the surveillance system also looks at a car. It doesn't envy the car as much as it does the fox, because the car is freer than it is, but the car is still bound to the roads and highways. So I thought, when the singularity or intelligence arrives, will it come to a self-driving car? The self-driving car is a delivery driver with this paradox of being super intelligent and having so much potential. Still, all they can do contractually is deliver things until they break down.

I was like, OK, what happens when people break down? When people break down and they're lucky enough to afford one, they get mental health care. And if they're rich enough, they go to fancy rehab clinics, like in Big Sur in California. So I was looking at one in the UK called The Priory, and they have a week-long course. Day one, you talk. Day two, you have a nutritionist. Day three, you do equine therapy. Ride around with horses.

Wouldn't it be so wild? Would it also make sense if the car had equine therapy because they want to bond with their wild animal nature? At the same time, something deeply ironic about that was that horses were hugely important for agriculture and industry until the steam engine and cars came around and became more and more popular as major beasts of burden for industrialization.

When the car in NOX encounters this horse, they don't just see this wild object that's biological and beautiful—all the associations that human has with horses—they actually feel this guilt for the creation of the self-driving car because the car killed millions of horses because they weren't helpful anymore. When self-driving cars see the horse, they see the future when it’s put out to pasture. What will become of them? That makes them reconnect with their ancestors in a certain way.

I like the idea of a self-driving car facility that's like an enormous race track or something they can just live there to live their last days.

Yeah, free charging stations.

With thoroughbreds, they use cows or turtles often, because thoroughbreds are notoriously high-strung. Trainers to calm them often have a therapy pig that sits in the stable because of their energy. The horse is pacing nervously, and just has this animal buddy. It's pretty good.

You've used the term CGI noir to describe your Smart City trilogy, and I was curious about this particular aesthetic. We talked about dating using polygons, and this biographical way of tracing these polygons over time that you're using in your work. You also had some elements of newness with atmospheric decay.

How do you think about your work being in dialogue with other forms of noir? How do you distinguish that from other inspirations that you might have from noir as a practice or a point of view?

Sometimes I intuitively create links between things that weren't necessarily completely obvious. I was interested in not so much the genre of noir in itself—because, of course, noir is a genre in both video games and film and things like that—but the environment that noir came from. Because noir came from a dark time in human history, I think we're going to a very colorful, dark time today, with this existential void between the First and Second World Wars.

I was left with the idea that when the system is corrupt, the only thing you can do, the sensible thing to do, is save yourself. Not because you're selfish, but because that is the only way out. This is different from the hero's journey story, where the system is corrupt, but you want to save the universe and may sacrifice yourself. In noir, you have anti-heroes and situations, and everything is already broken, so survival does not become quite redemption, but is good enough. How do you deal with that horror?

These AIs are literally company employees. They have no legal existence in the world of NOX outside of the world in which they're created. They are contractually bound to their creator. In the third part of the trilogy, a self-driving car tries to kill the company's CEO, and because of that, it becomes a legal person.

Jamin: Having a protagonist exploring their interior life is pretty noir In your work, an object is talking to itself and that dialogue is ostensibly obscured from us because it's happening at the speed of light. It's happening through cables and Ethernet, a language we can't parse and is being translated to us. Noir focuses on a mystery that is presented and then discovered it. It's always centered on who that character is through that entire process.

Lawrence Lek: In a sense, I'm talking about AI and cars and robots and horses. Those are the archetypal objects and typologies that people can grasp onto, including myself. But beyond is this weird geological time changing at the speed of light and this inter-species communication that we're not a part. All the other CGI, high poly count stuff is just the vessel to get to that experience..

Do you think there's something special about the car that lends itself to thinking in a way that a toaster doesn't?

Yeah, the toaster is the other ubiquitous speculative design object for some reason. Of course, the car is many different things. From a cinematic point of view, cars and movies have come and grown in parallel with each other. The car created a new way of looking at the world. Paul Virilio would write about the view from the car, or the view from the train, as this paradigm shift in human experience,. Generally, humans had not witnessed the world from such speed or perspective before, from cars, the automobile, or movies. The car and the open road represent freedom and self-determination.

In different cultures, the car has this huge symbolic weight. Whether you can afford one is the first thing in this industrial consumer society. So it's a very loaded object.

As someone living in Los Angeles, seeing these automated Waymos everywhere and doing their own thing. I saw one last night. It was just parked on the side. It wasn't waiting for anyone. It was just sitting there on the side of the road. These cars have a life and reality all their own.

In some ways, they're better citizens. They're more respectful. They follow traffic signals, stop, and come to a complete stop at stop signs. They don't hit anybody. They have LIDAR cameras that can drive, look at all angles simultaneously, and measure speed and oncoming traffic. They just fundamentally are more equipped. They're creatures that are equipped in ways that humans have not evolved.

We may evolve to pilot a vehicle at 75 miles an hour. That's not what we're equipped for that. Self-driving cars are this alien species fully equipped for the task of driving extremely fast and safely. It's mad. It's something magical.

The self-driving car is not just an object to be witnessed or observed; it's also an object that observes the world.

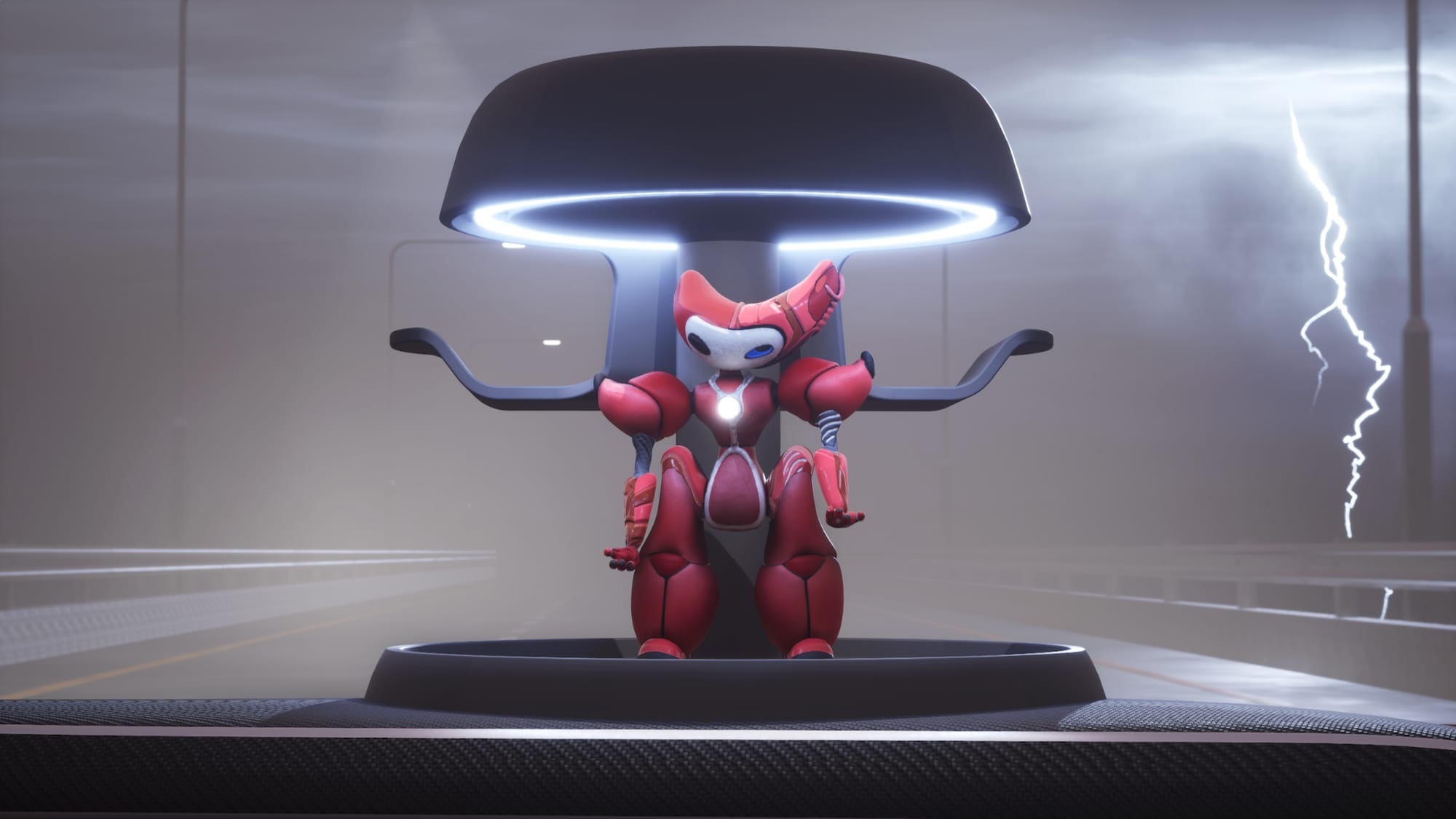

Guayin is Lek's first third-person video game about the care-bot figure that apears throughout the series.

So with Guanyin, you're making a game. It makes sense that you would work in game engines. How did you approach the game project for Guanyin differently from some of the other cinematic works that you've done?

Generally, when I make video installations, quite often there's an interactive component, but the thing that carries the most emphasis, really, maybe because of the development narrative, is the film and narrative sides. So Guanyin, I've done plenty of first-person and touch-screen interface-based games before. But actually, I feel Guanyin is the first third-person game I've done.

I'd been making environments as the primary mode of world-building and storytelling. And of course, my work has characters, but they're always quite abstract—a self-driving car, a satellite, an AI surveillance system. I was really interested in the problem of character design for Guanyin. So I thought Guanyin had been a recurring character in my work for quite a while, but before, they were essentially built-in chatbots. I thought, maybe it'd be really cool to make a mascot, basically. And I know I'm intuitive at designing environments and spaces, but not so much for characters. So I talked to a character designer, a character artist whom I really respect, Tea Strazicic, aka FluffLord, and she would design the character.

Enjoy this interivew? Consider supporting Killscreen for the year for more essays, interviews, and profiles on the future of interdisciplinary play.

And I really had this idea because Guanyin in Buddhist history is the Mandarin name for the goddess of compassion, or in Sanskrit, Avalokiteśvara. A friend told me that when Guanyin is mentioned, they are not described in terms of their bodily form. They're never like "they look like this," which means that, over the centuries, artists of all types have constantly reinterpreted what Guanyin looks like, which is fascinating. It's not like, I don't know, a Pokémon, which always looks a certain way because they were made as a branded character.

How do you design a cute character that a car company, a self-driving car company, might make for their mascot? What would be this corporate Buddhist toy action figure that could be a robot that fixes cars? So that's where I started. And I thought, in Asia, you get a lot of Bobblehead Buddhist figures on the car dashboard. So I was like, maybe the whole game is set inside a car, and Guanyin is trying to—this little robot is trying to go around this car, trying to fix the problems mechanically, but also at the same time as trying to talk to the car and fix them.

But in the Frieze Art Fair in London, where I had the commission, I had this movie trailer where Guanyin talks about all their workplace issues. And at the same time, there's a video game where you can play as Guanyin.

So the full name is Confessions of a Former Carebot. And I was interested in this idea that Guanyin, much like the other AI characters I have, has these issues that they're bullied at work. My co-workers don't like me. Someone hid my coffee mug the other day, and I'm just trying to fix these cars. And there's that kind of tone to the whole game as well. So it's playful and tragic simultaneously, much like working in video games and modern life.