My wife teaches high school history and, like many educators, is deeply worried about AI's impact on her students' academic lives. It’s a source of constant conversation—I’m no AI-optimist, but I’m far more rosy about the possibilities of the technology than she is. She laments that teachers weren’t brought into the 2022 release of ChatGPT, and that it was foisted upon educators without warning or care. And now administrations everywhere are pushing AI as the future of her field, again with very little input from actual practitioners.

I assure her, “Just wait until academics figure out the best way to use LLMs.” She justifiably rolls her eyes. I’m not moving the goalposts, of course, I’m just waiting. So, finding the work of Michael Peter Hoffman, hopefully, will tip the rhetorical balance in my favor.

Hoffman is a researcher who occupies an unusual position at the intersection of two disciplines that rarely speak to each other. By day, he builds and evaluates AI models at the Leibniz-Rechenzentrum, one of Germany's premier supercomputing centers in Munich. By training, he is an anthropologist who spent three to four years doing fieldwork in Nepal and India—studying debt-bonded laborers in the lowlands of Western Nepal, visiting brick kilns and construction sites, and descending into a sand mine where hundreds of families dug and sold sand while a whole economy churned invisibly around them. It was in that sand mine, he says, that the idea first struck him: the stories he was gathering were extraordinary, but the academic monographs that would contain them would reach almost no one.

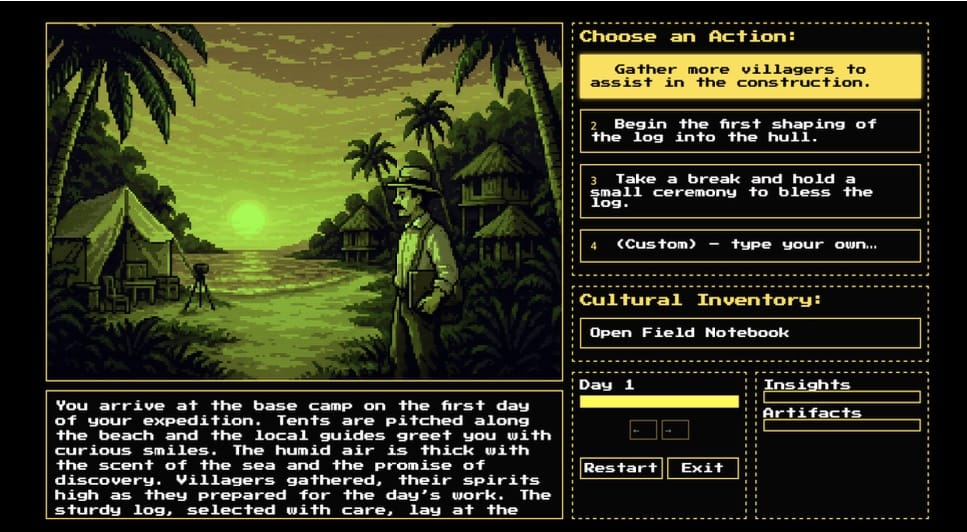

His solution is what he calls an "Anthrogame"—a game that conveys anthropological knowledge with ethnographic thickness. In a series of papers beginning in 2024, Hoffman and his collaborators at Freie Universität Berlin fed Bronislaw Malinowski's Argonauts of the Western Pacific, a standard Anthro 101 text, into a Large Language Model and produced an “AI-native” text adventure where players step into the role of a fieldworker arriving on the islands, Malinowski’s academic advisor, or Malinowski himself.

The results were promising and imperfect: the AI struggled with biographical depth, tended toward monotonic responses over extended play, and was susceptible to hallucination. But it also generated genuine curiosity. Many who playtested the game were surprised to find themselves drawn into a world they'd never encountered. Anthropologists, predictably the harshest critics, still wanted to try it in their classrooms.

What follows is a conversation about why anthropology may be the original worldbuilding discipline, why game makers have been reluctant to set their work in real cultures rather than fictional ones, and what it means to translate a text—already a translation of a life world—into something you can play.

JAMIN WARREN: How did you make your way to artificial intelligence as an anthropologist? Was your background as an anthropologist first, or were you already interested in the technology?

MICHAEL HOFFMAN: AI is something I started very early. When I was 16, 17, I started programming and worked on little games—board games, actually. I started out as a computer scientist in Munich, and from there went into anthropology to study something different.

JW: When you're explaining what an anthropologist does to someone who's not familiar with the field, what's the dinner party definition?

MH: An anthropologist goes to another setting—usually further away—and you dive into a culture for at least 12 months, to get a whole yearly cycle. In my case, I went to Western Nepal, to a town called Tikapur. I studied the lives, politics, and economics of former debt-bonded laborers. You describe these systems, and it's a translation process.

JW: I can understand the appeal of games as a medium for this—many of them put you in a different place, in a different time, and expect you to make your way there. As you noted in your papers, there is a history of in-game anthropologies, applying anthropological tools as virtual worlds come to resemble human societies. For a skeptic, what is the value of doing that?

MH: My take is that anthropologists should make video games. There are hardly any who have done it, because game-making is really hard. But not everyone has the fortune to dive into another culture. Games could be a way to give people a chance to experience such settings.

AI-generated scene from the game ’Malinowski’s Lens’ , Bronislaw Malinowski with natives on Trobriand Islands; between October 1917 and October 1918

JW: How are you defining the term "Anthrogame"?

MH: An Anthrogame conveys cultural knowledge and anthropological insights to an audience who wants to play it. The key characteristic is that it's "ethnographically thick"—a term anthropologists use. You want to describe a culture not superficially but in depth. If you can convey that thick writing into a game, it becomes an Anthrogame.

JW: Game genres are usually focused on mechanics—is it a first-person shooter, is it a platformer, etc. As a result, you end up with less experimentation on the setting. Games have a history of doing history, at least, partly from the legacy of tabletop roleplaying and wargaming. But stepping into a real culture and experiencing it—that's not a place games have spent much time. Why do you think game makers have stayed away from that?

MH: If you want to do this seriously, you have to dive into a culture first, and that takes a long time. Fictional games give you more freedom—you're not constrained by reality. With an anthropological game, you should ground it in the reality of the society and be respectful towards the community you're representing. It's also a double translation—anthropological books are already one anthropologist's subjective view, and then you translate that again into a game.

JW: What compelled you to create AI-driven games for a teaching context?

MH: It started out of a frustration. I spent three to four years doing fieldwork in Nepal and India, and when you write your work up, you write it for a limited academic audience. Reading is in decline, let's be honest. I'm not saying this should replace reading—I'm a big fan of books—but this could be an appetizer. You play it for a bit, you get interested, and then you start to read the book.

JW: Walk me through developing the game. You chose interactive fiction as the format—how do you go from the text to something playable?

MH: When there was the ChatGPT, I thought something like The Oregon Trail would be a good start in a very easy way. If you want to turn Malinowski's book into a 3D game, you have to produce assets that look like the Trobriands, and you won't find that on the Unity Store. So stay without graphics first, then go toward the hard parts. My day job is at a Supercomputing Center in Germany building AI models, so it's an interesting way to apply that off-hours.

JW: "AI-powered game" has become this term that gets thrown around. When you say "AI-native game," what does that mean functionally in terms of how the game expresses itself?

The text gets fed into a Large Language Model through a Retrieval Augmented Generation technique. That means you force the LLM to really just read from the book. The output is a short description of a scene, and then you have different scene choices, and you can pick them.

It's like a Dungeons & Dragons setting where the LLM is the dungeon master and creates the scenes, and then you are stepping into the role of the anthropologist. You also have an open input field—instead of these three options, you could say whatever. Like, go to the center of the island or try to go to a canoe and go to the next island. The advantage is that every game is different. Once you build such a structure, you could theoretically do it with a whole different range of anthropological books or historical books.

JW: With students playing the game, was there a particular interaction that stood out—something the game revealed in the play structure that was a sign you were moving in the right direction?

MH: Students tried very quickly to find a shortcut to solve the four quests. That was surprising for me, and also refreshing—they took a gamer's approach and tried to hack it.

JW: Yeah, that happens.