In 2017, professor Ian Bogost proudly declared in The Atlantic that games don't need stories. "That’s a problem to be ignored rather than solved. Games’ obsession with story obscures more ambitious goals anyway," he wrote. Bogost's general point was that stories are what you build on top of a medium's true material foundations, and games are actually best at disassembling ordinary objects and systems and reassembling them in surprising new ways.

"There was a really big trend in the 2000s to have your story expressed explicitly through the mechanics," LA-based game designer Toby Alden says. 'The joke I always make is a platformer where it’s like, “I’m grappling with the loss of my wife."

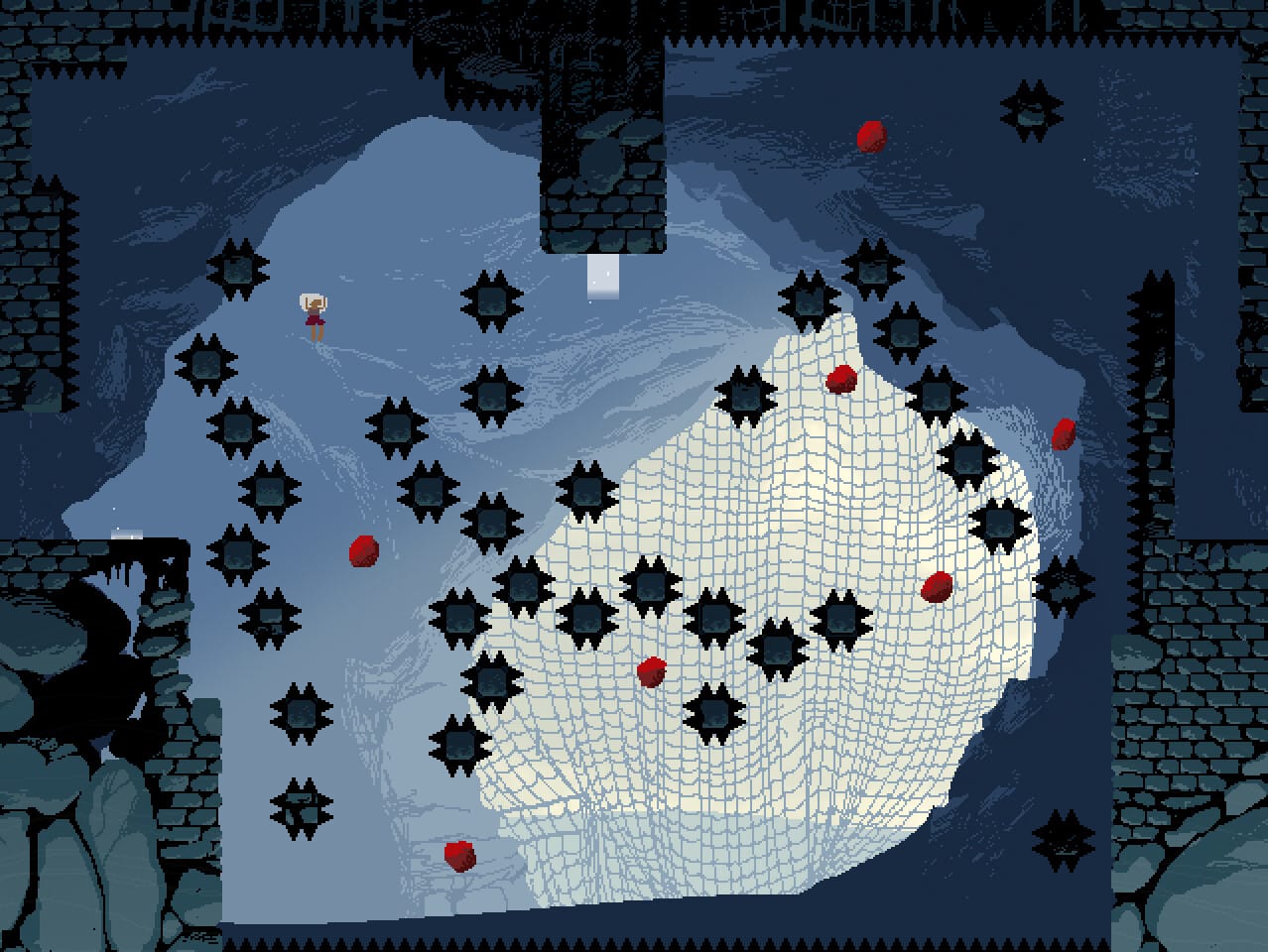

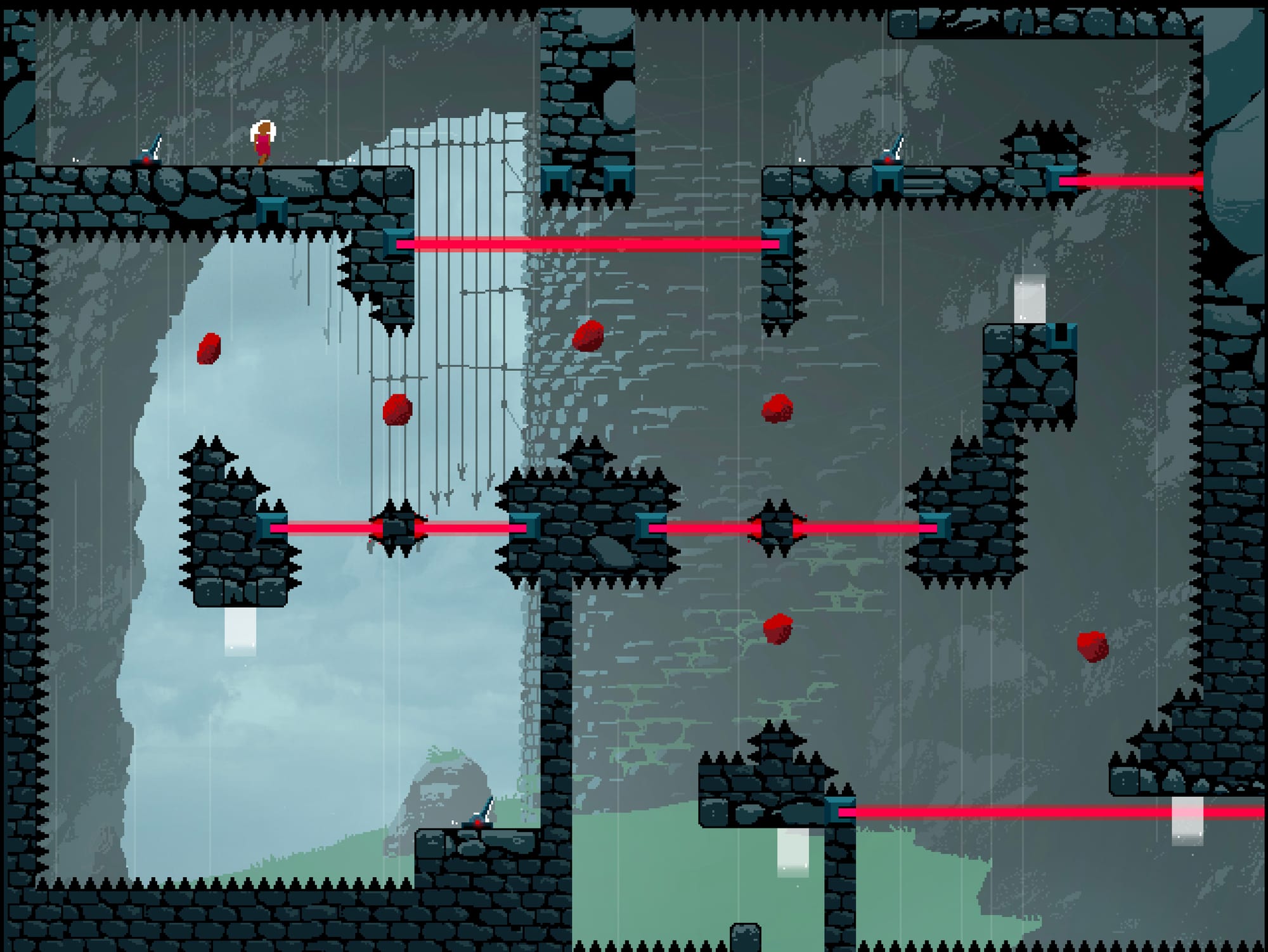

Right around the same time Bogost penned his broadside, brothers Toby and Ben Alden began updating a pet project called Love, a hyper-difficult "masocore" game that almost no one finished and, to Bogost's point, was devoid of any narrative. But even for a physics-minded designer like Alden, the allure of telling some kind of story, even if the game itself doesn't demand it, was simply too great. But rather than deliver the story through the player's actions themselves, Love Eternal, the newly-released game simply leans into the abstraction.

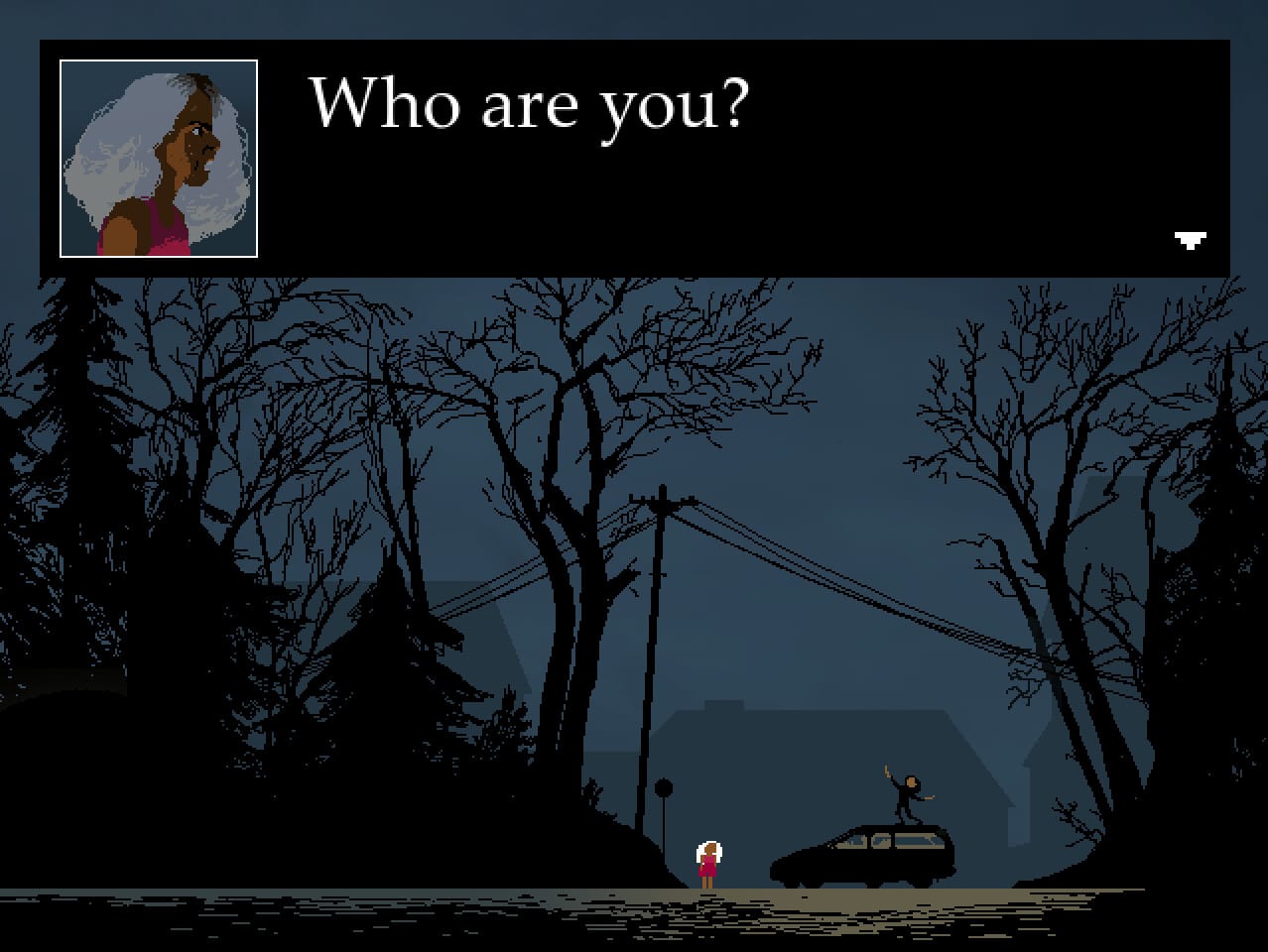

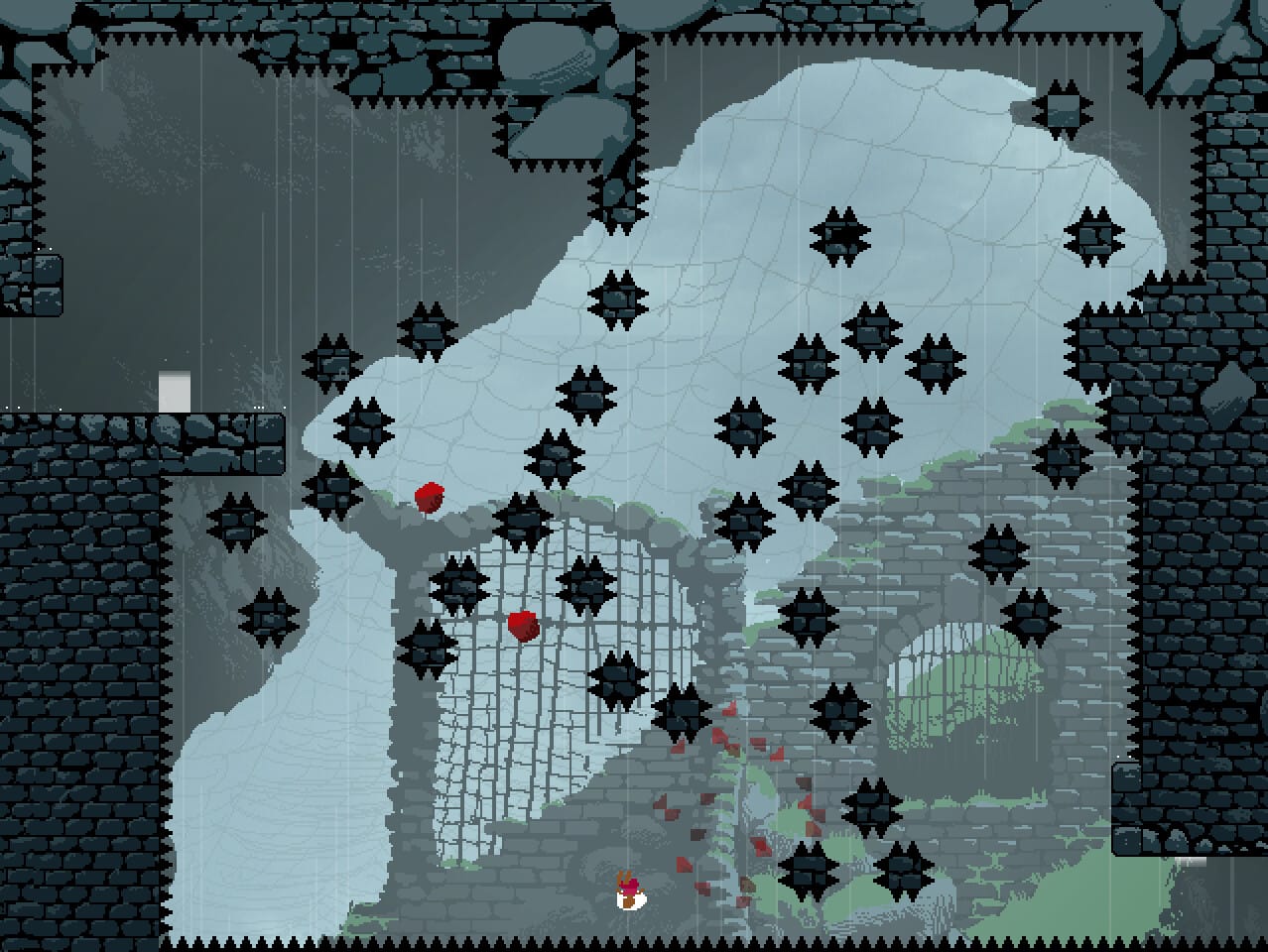

You are a Maya, a girl who's family has disappeared during dinner, and you're dropped into a perlious world in clear disrepair. You father has become some kind of wraith and a childhood friend has become something else entirely. It's all eerie but also deliberately indecipherable. In this conversation, Toby and I talk about the influence of ambient music like Aphex Twin, the perils of working with your brother, and how to make games that feel like playing music.

How Do You Design a Level That Feels Like Playing a Theremin?

JAMIN WARREN: I first found out about your work from Jenna Caravello, who recommended we connect. I’d reached out to her because I was interested in what was happening with animators in Los Angeles given their relationship to games. How did you make your way into game-making?

TOBY: Almost as long as I can remember, it’s been something I’ve wanted to do. Around high school, I played Cave Story for the first time and became aware that making a game was something one person could do. As soon as that was on my radar, I began taking stabs at it—making mods for Cave Story, trying to make Flash games. I started a lot of projects and didn’t finish any until a little after college. But the desire was there from a young age.

WARREN: You’ve mentioned making music and wanting sound to fill the room. Tell me about the relationship between your music practice and your games.

TOBY: I’ve made music for a long time—it developed parallel to game making, with a similar trajectory of false starts until around college. A little after that, I started DJing, which I’ve done for almost a decade. Those three form the brunt of my artistic output: DJing, making music, making games. Music and games are very complementary—obviously because games contain music. But there’s almost a parallel between playing a game and playing an instrument, where it produces sound that fills a room. I think a lot about what one of my games would be like if you were in the room but weren’t the one playing—you just heard it. Would it be abrasive? Or would it be more soothing, ambient background noise? Which is what I usually lean towards.

WARREN: What kind of music were you DJing? Were there particular artists that pulled you into music early on?

TOBY: A lot of what I was inspired by early on was sample-based music—DJ Shadow, Burial, IDM like Aphex Twin, and Kettel. A lot of rap production, like 36 Chambers. Sample-based stuff especially had a big influence because it fit the way I thought about sounds—through experimenting, sampling, and re-sampling. And ambient music. I’ve always listened to a lot of it, and that’s a big part of what I DJ now—stuff that leans toward ambient, dub, ambient techno, down-tempo.

WARREN: You didn’t do the music for Love Eternal yourself (Emily Glass did.) Even if you’re not the person making the music, the decision to contract somebody who fits a particular vision speaks to taste. How did you connect with Emily? Did you start with a score in mind?

TOBY: She was my first choice because she was the most talented person I knew who made music, and she had the emotional depth and richness of sound I thought would fit really well. Being in the position of directing a project requires this balance of egotism and humility—the things you know you can do well, you want to be confident in. But you really need to know what you’re not good at and then trust the people you assign those roles to. There wasn’t a lot of back and forth—small adjustments to fit technical specifications, but for the most part, I could let them do what I knew they were good at. I wanted the music to be ambient in the classical Brian Eno sense—where if you pay attention, a lot of nuance comes out, but if you don’t, it recedes into the background. I said something along those lines in my original pitch to Emily, and the first thing I got back I was like, “Yep. That’s exactly it.”

Do Games Need to Explain Their Own Mechanics?

WARREN: For the story—you’ve said it wasn’t planned in a particular way. I typically don’t think of platformers as games where story isn’t really important anyway. Were there moments where what the game required mechanically was at odds with what you wanted to express narratively?

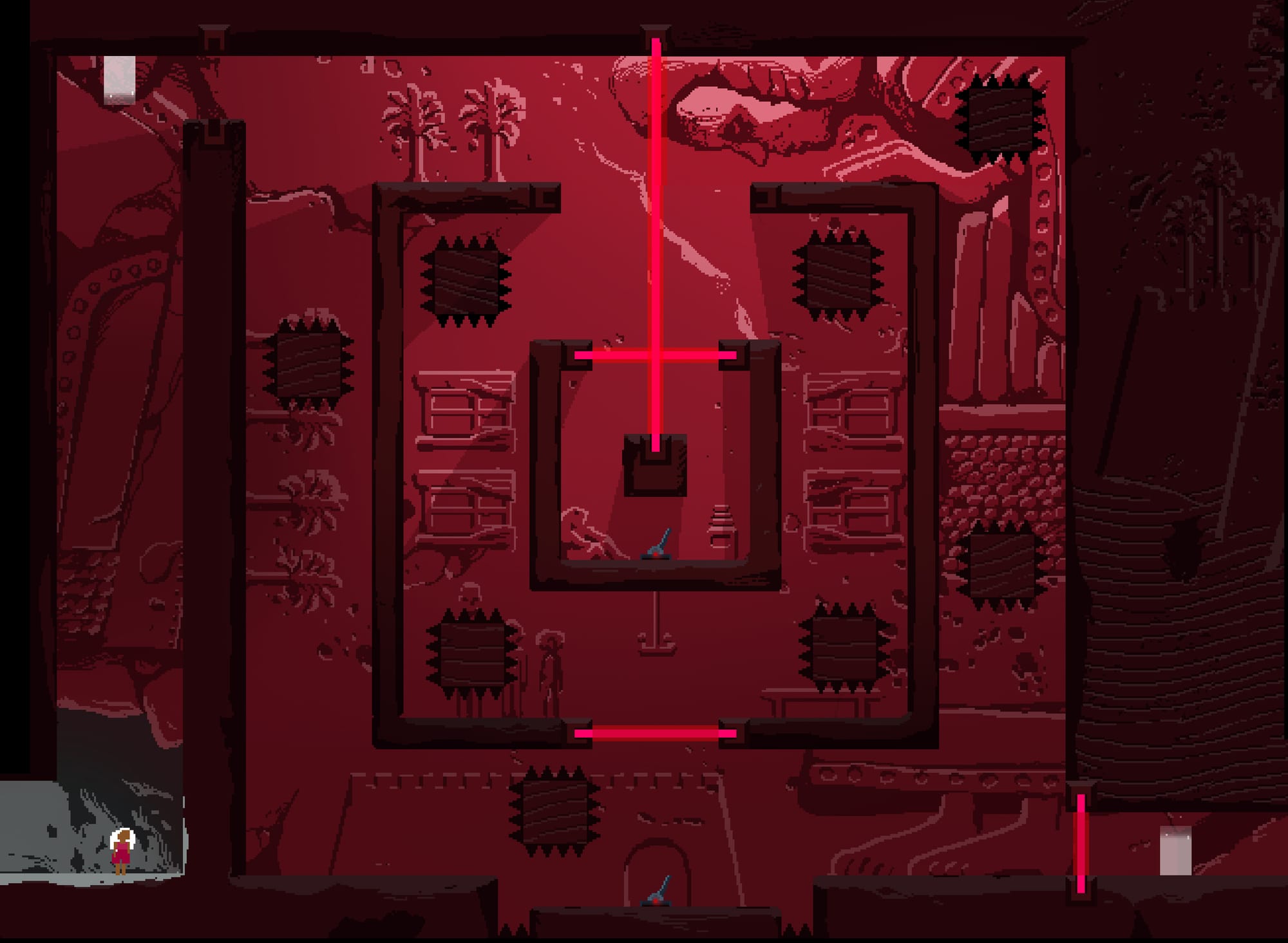

TOBY: No, there wasn’t. There was a really big trend in the 2000s where it was very chic to have your story expressed explicitly through the mechanics—or have the mechanics cleverly comment on your story. The joke I always make is a platformer where it’s like, “I’m grappling with the loss of my wife.” But I think one of the strengths of video games is that people are willing to accept a level of abstraction. They don’t actually find it jarring to do a bunch of arbitrary platforming and then have a story beat. The gravity mechanic—where you can flip gravity—it’s never explained. There’s no in-game reason why you can do that. But I’ve never had anyone ask me why she can do that. I think video games are allowed to operate with this dream-like logic, and you give up some storytelling power if you ignore that. It was very freeing to write the story in a more abstract way that didn’t explain everything. There’s no moment in the game where Maya looks to the camera and says, “What’s going on? Why am I in this castle?”

WARREN: The way the game functions is at this subconscious state of working through individual levels. When I would think about things too much, it made it difficult. It felt more like playing a theremin than playing a piano—like playing a fretless bass rather than a harp. Can you tell me about what the feel of the levels should be like?

TOBY: A lot of it comes down to intuition and experimentation. There’s a lot of just opening the level editor, smearing some spikes and geometry around, hopping into the game, seeing what it feels like. And then maybe you have one particular moment where it’s like, “Oh, that was really satisfying.” Maybe I can do that a second time in a slightly different way, or structure the whole level around it. That happens more often than sitting down with a fully formed idea. Despite what YouTube essays would have you believe, there aren’t really rules I follow to produce a brilliant level. It’s a lot more experimenting, playing, and seeing what feels fun or interesting.