When I catch up with Harriet Davey, they've just returned from a week-long planning campaign with a dozen co-workers. They were deep in the playing phases for their next big project and working on getting their collective story right to share internally and make big changes in how they work together. “We’re getting our story straight,” they say. When running a D&D campaign with the scale of West Marches, that type of commitment is a requirement. (Did you think I was talking about a job?)

As you can imagine, Davey floats between worlds and universes as a digital artist, virtual photographer, terraformer, and fashion designer. As part of SBLMTN Studio, they translate fantastic lookbooks for their feral subjects into walk-ready apparel. As part of Circa x Dazed’s selection, their work was screened at the iconic Picadilly Lights and worldwide. And as an educator on Twitch and in-person, Davey shares their craft with others.

Davey represents a new generation of artists who treat game engines not as entertainment platforms but as laboratories for identity exploration and radical body representation. Based in Berlin, this self-taught 3D artist has transformed gaming's character creation tools into instruments of queer resistance, creating "glossy, luminescent alien-like creatures" that challenge the male-dominated aesthetics of virtual worlds.

–

Jamin: Can you tell me a bit about those earliest game-playing days and connect the dots between those earliest and some of the work you're doing today?

Harriet: Yeah. I was actually trying to remember the first video game I ever played. I was playing on an iPod Touch, the first-generation iPod Touch at the time, and it was a ripoff of GTA.

Before that, I'd spend time at friends' houses. I had a friend who was really into World of Warcraft, and all I would do was go over to his house. I would sit there making elves and new characters and then say, Oh, let's do it again. I wanna make another character. And he'd say, Oh, I just wanna level up my level 600 or whatever. And I'd say, no, I wanna make another character, please.

I begged my mom, I was like, please, please, please, please, can I get World of Warcraft? And she just refused because, to be honest, I think who knew how addicted I would've gotten to it. So it was fair.

It's like cigarettes, honestly. It's best that your mom intervened.

Yeah. It would've been a slippery slope for me.

But back to childhood, we weren't allowed many video games. The wifi at home was too slow to play online, so I would have to play the campaign alone. And yeah. I grew up in the middle of nowhere. Just one mb internet…on a good day. Online games, no chance. Even downloading games, it would take a week sometimes to download a game.

Right. Oh my gosh.

So it was really inaccessible for me. From all ends, I was at odds, and when I eventually left home and went to uni, I built a gaming PC and started playing Skyrim. That was the first game I wanted to play.

Then, I discovered 3D art because I realized I'd built this gaming PC. I started thinking about how video games were made and wanted to take the lid off and look inside. And yeah, it very fluidly followed.

Selects from Harriet's recent work

Were you always interested in characters, 3D modeled bodies, or avatars? Was that part of your gameplay interest?

Yeah. For me, the character design of any game was always the character creation menu. I still spend hours doing that, because it is my favorite part. I wanna see every setting that is even possible in these things. I'm also interested in what developers and modelers decide is the default character. What are the six hairstyles we chose to put into this game? Or what are the 23 ones that we now have in modern games?

Seeing these decisions and then seeing the lack of ones that interested me. They were so boring and normal and male, or super sexy, and I never really felt like there was anything that I was really drawn to. And so I spent so long because I wanted to make the characters weird in a scenario where they weren't ever supposed to look so strange. It's still my favorite part of any game.

It's interesting with games for designers—well, first of all, with character customization, which not all games feature. In some ways, video games in particular were pretty resistant to the idea that you should be able to choose a different character. That definitely comes from—it feels like it comes more from a role-playing game perspective. That was a part of early role-playing games, so it made sense when they moved to computers. The expansive side of role-playing games is expressed through these complex systems, but not through the characters—the character customization was pretty limited. Even if you had a huge world to explore, what your character looked like remained pretty limited.

So it is unfortunate that side—role-playing games in a digital context, I think, have had this weird relationship where it’s trying to express this systemic complexity of a role-playing game system alongside the improvisational nature of tabletop role-playing games. And those are often in tension in a video game context because there are limitations to what you can do on a machine.

It does seem, though, at least now, with Baldur's Gate and things like that, we've resolved that there’s a wide diversity for characters. And many things that hold it back are frankly more of the cultural side. The artistic side of it, oh, you need to play as a person who looks exactly like this.

Even Baldur's Gate isn't great, for the most part.

It has a great character creation selection, but is still lacking on some fronts. Everyone is still very toned and very sexy and very muscly, which someone would argue, Oh, it's someone running around with armor on their back. But it's also like you look at Olympic athletes, they don't all look like this. But yeah, hopefully they keep pushing.

It comes down to who is making the games at the end of the day. If it's a group of 15 white guys, they will make 15 white guy options in the game. They see themselves and know how they look, based on their experiences in the world.

How did you see the male gaze express itself through some character design systems when you were playing games or messing with The Sims or some of these early character creators? How did you see the hegemony of the makers—predominantly white, cis male point of view—in terms of the character design? You probably noticed that early on when you made characters inside games.

It's a meme, but it comes down to the armor. I remember going to a place called the Royal Armouries, where I grew up in Leeds, and it's a museum for armor and weapons. They have all these ancient medieval British, French, and Norman armor sets, including some for women. I was probably maybe 12 when I saw one of these stupid breastplate with boobs things, and I was technically annoyed at the specifics of how something like that would work,

Breastplates have always been rounded and potbelly to deflect stuff off them. The strike glanced away from the body, and I wondered, Why are you putting a divot in the middle of the chest.

Many people get introduced to medieval history through games and conveniently ignore why you might design armor in a particular way.

When you started moving over into Daz Studio and then Unreal, did you find that there were the same kind of biases in those digital tools that you saw in game contexts?

Late 15th century breastplate of 'Gothic' form from Royal Armouries vs. Lineage 2

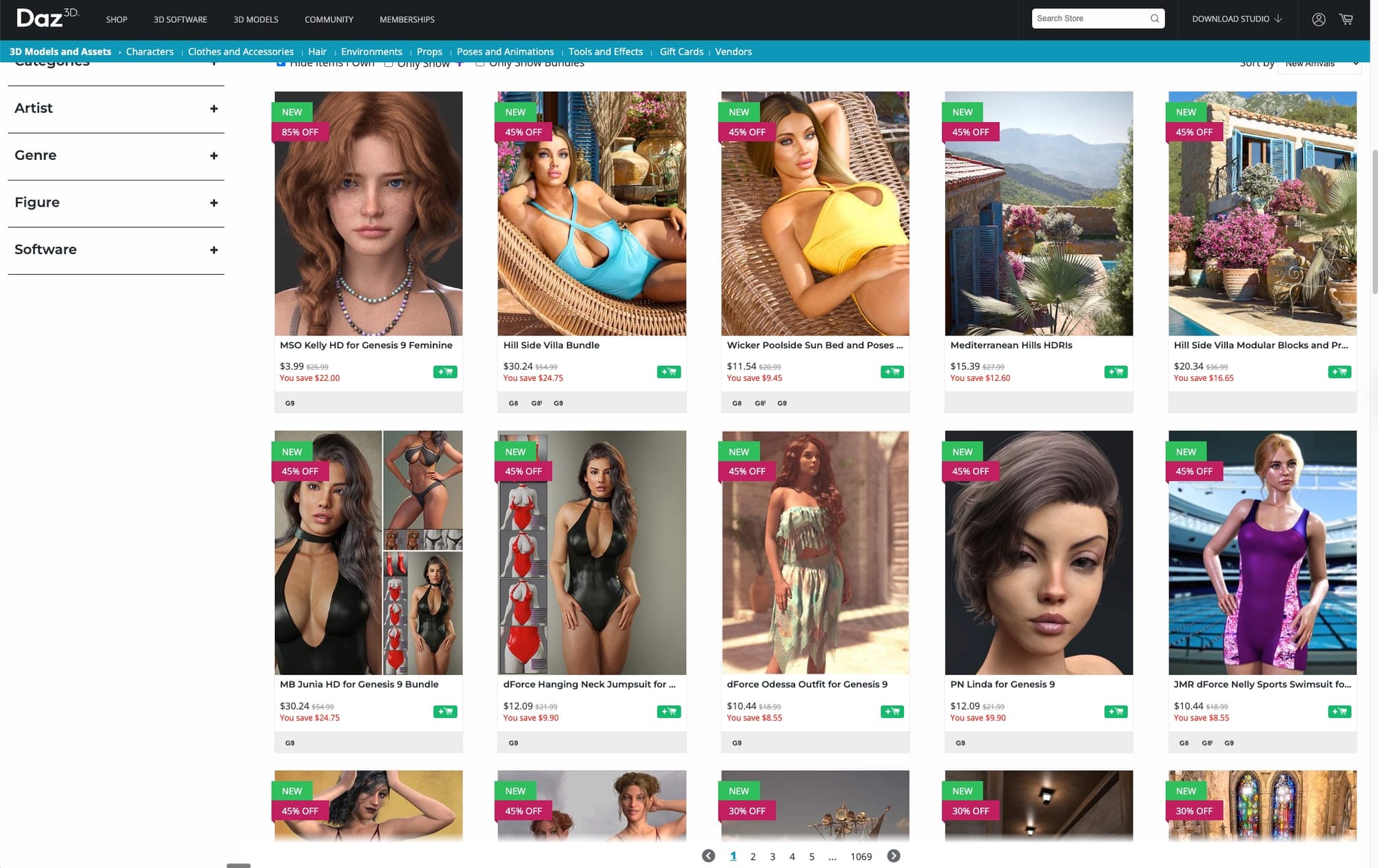

Daz Studio is worse than where the gaming industry is now. Daz Studio is like stepping into a time machine 10 years ago and seeing how things were in the gaming industry. If you were to go right now, do you know what I would do?

Let's see what is on the Daz store page if you like 3D models. OK. It is a sexy woman wearing a tiny little panty bra thing. That was the first thing I saw. You scroll down. Sexy woman. Sexy woman. There's a henchman with tattoos on, then there's some tentacle—oh my God, this—

I'm looking at this octopus man.

Yeah, pretty horrific, but it's always funny. I teach a lot in universities, teaching students 3D Blender and Daz Studio, and we always have this moment when I show them this tool. Then I feel almost guilty that I'm showing them this thing that completely rejects my personal thoughts and feelings.

Still, it's a big part of my practice that I'm taking this fetishizing, sexualizing tool and pushing and pulling it towards my terms to work within its own parameters.

But I still feel this horrific ickiness when I have to show students this because it feels inappropriate. It's so archaic. For a while, it seemed like maybe they were going in a slightly different direction. They were bringing out some things for Pride. They were adding some top surgery scar morphs and stuff like that. But I think in the last couple of years, like everything in the world, they've also relaxed, regressed, or returned to what they know.

Jamin: When did you start this oppositional relationship with the software? What were some of the things you were doing with the tools to make sure they reflected the more fluid bodies and identities that have become a hallmark of your work?

Harriet: Yeah, so when I first started, they actually had a gender neutral base Genesis. It was just Genesis, I think. And back then, you had this non-binary looking default human mishmash. And you could take it either way—you could take face to be more feminine, parts of the body you could take more masculine. The textures given for them were really bad as a starting point. Then they split Genesis 3 and 8 into male and female bases.

I would download all of them and play around with them, even if they were horrific and sexy, which they always were. And trying to fit super feminine things onto the male models when they weren't even made for that. And trying to mix things a little bit.

I start with the female base, which I then try to make quite masculine, and I spend some time resculpting on top of them and taking them all the way to the most masculine and least feminine that I could do. And then finding another middle ground. So they sit mostly now in this middling fluid center, but usually still starting with the female base.

Yeah. One of the distinct pieces of your work is this shine, this shiny, this wet look that you have.

Yeah, I mean if anyone is a 3D artist, they know that making things shiny is a little bit of a cheat to kind of—upping the, if I say the wow factor of how something looks. It can be cheap-looking, and it's a bit lazy, but it was something that I was doing at the beginning because I never once wanted a realistic skin texture. I also find realism gross, like replicating this soft, real rough texture that is never quite realistic and still plasticky.

Upping the specular and having things a little shiny is an easy way to avoid the uncanny valley. I'm not trying to replicate realness, and by solidly moving away from that, I never have to deal with the ah, this thing is scary because it looks like a doll.

The characters feel more real because they feel like their own thing. They're not replicating reality, but they are—it's a photograph of a creature. It's not a render of a human that looks almost realistic.

The bodies that you're working with are in between. They're humanish. They're humanlike. But it bears some features that would be familiar to someone who plays a lot of video games. They also have this feral, animalistic element to it. They're not creatures of this particular world.

Yeah.

So you've been moving into Unreal, right?

Yeah. I think it's quite a natural progression for many 3D artists. If you're working with characters and are interested in games, you want to see your work moving in real time or controllable, and not having to wait two nights for your render to see if the animation even looks good.

I got a motion capture suit (Thank you, Rokoko!), and I was really interested in the live, real-time motion capture. I ended up working with some performers and dancers, putting them in the suit because I love being in the suit. It's also fun, but I also danced when I was younger. It's always nice for a dancer to see their body movements from another angle.

We're used to seeing how we move in a mirror and understand that relationship with our body. But if I move the camera out, I can show them this movement they're doing from any angle--from above, from behind--and suddenly they have this completely different relationship with the movement.

At the end of last year, I worked on an interactive performance piece called State of Play: شهر بازی with Tara Habibzadeh, Mati Bratkowski. It's a retelling of an ancient Persian mythology. We had a motion capture suit performer playing the part of this white demon, Div-e Sepid. We got the tail and wings to have physics as the performer moved, and then the performer had this virtual appendage reacting to their movements. It was a whole other level.

Photos: Ben Moenks

Can you tell me a little about your relationship to that industry and maybe some of the relationships between fashion and games that you see emerging?

Yeah, I'm also the founder of SBLMTN Studio. There are three of us. I'm the 3D artist. We have another digital fashion designer and a physical fashion designer. We put on non-traditional fashion shows, so they were performances in which we had the same setup—a dancer, a performer in the motion capture suit, and a digital world with extra assets and extra outfits.

We haven't done them for a while, and yeah, fashion is not something I'm that interested in, which is quite funny. In the real world, I like clothes. I don't follow things that religiously or go to many shows or anything like that, but it seems natural that if you have digital characters, at some point, they should maybe wear clothes.

I like the characters without clothing because I think a character doesn't necessarily need it. But one time I remember my grandma saying to me, she was like, Harriet, I do prefer when they have clothes on.

Over the years, there have been different overtures from fashion to games. Like Nicholas Ghesquière from Louis Vuitton with Final Fantasy crossover...

The Death Stranding games—

Right. Yeah.

Errolson from Acronym.

I think you're stepping into the breach here in some ways. Because I feel like most—to our point, our discussion earlier—a lot of game makers come from similar backgrounds, similar interests, and when they create opportunities for extraordinary opportunities. Still, they don't really seem to have an interest in them.

So you have digital—Fortnite, or some games that allow for digital clothing. Still, they have no interest in working with people in fashion for said digital clothing.

So I think it's interesting that you're kind of—there's an opportunity there to do the work that a video game company might do. But they don't pursue, they don't really perceive it as being part of their quote-unquote brand.

Also, the audience is children sometimes.

Haha, yeah.

I'd seen some of the work that you'd done with figure studies or framing environments. Can you tell me about the importance of environments in your practice? There is this kind of unseen element, both the composition of the characters and how you're getting them to gesture, but also all of the backgrounds and the contexts, right? They're not just characters in a black space or alone—you're also designing these environments for them to live in.

You're taking a photographer's eye. The work is between many different spaces, but you're casting your creatures like a photographer to pick the characters and then document them.

Yeah, the characters always come first, and the landscapes 99 percent of the time come second. They give context clues and ideas about who this character is, their personality, where they come from, where they live, and how they inhabit a world.

For a long time, I was making all of these environments and imagining these creatures interacting with them and how they functioned in the worlds that they were inside. And I thought I was doing a pretty good job of making quite diverse scenery. Then someone asked me where I grew up, and I showed them pictures of the countryside in the West Yorkshire Moorland. And they were like, *Oh, it looks exactly like all the worlds you are making for the characters.*

And I was like, *Oh. You're actually 100 percent right.* [laughts] So I grew up in the middle of nowhere, as much as you can in England--because it's a pretty densely populated country.

Yeah.

Harriet: Unlike in America, where you have swaths of land with nothing in between. The nearest house was across a field, and then apart from that, the closest house was maybe nearly a mile away and surrounded by sheep and moorland. And you could look out the window and see this stretching brown rolling hillside. It looks desolate, like nothing grows there.

All the heather comes out in the autumn, and the whole thing turns purple. In areas, there are purples, browns, shrubbery, no trees, and exposed rock. We would also often have a lot of hill fires in which the entire hillside would burn away, and it would just be ash some months.

For instance, the height of the shrubs is always quite low, and they are always quite dense, and they look desolate and infertile from afar if you zoom out. But when you zoom in! You have little pockets of life, and flowers poke through, and you can imagine that there might be tiny birds nesting.

I was not thinking about home when I was making any of the landscapes, but it was maybe something that I was comfortable with. It was very subconsciously this sort of semi-homesickness of the countryside.

I lived there until I was 17 or so, 18. It was super formative for me, and I think I probably still miss it.