Simon Flesser sits in his Malmö studio, surrounded by 15 years of digital ghosts.

Behind him, I spy the unmistakable presence of a hulking phonograph, the iPhone of the 19th century. It's a curious choice, and for someone who has spent the entirety of their professional career making games in digital environments, the reminder of a once-passed technology sums up their current focus: preserving their own past.

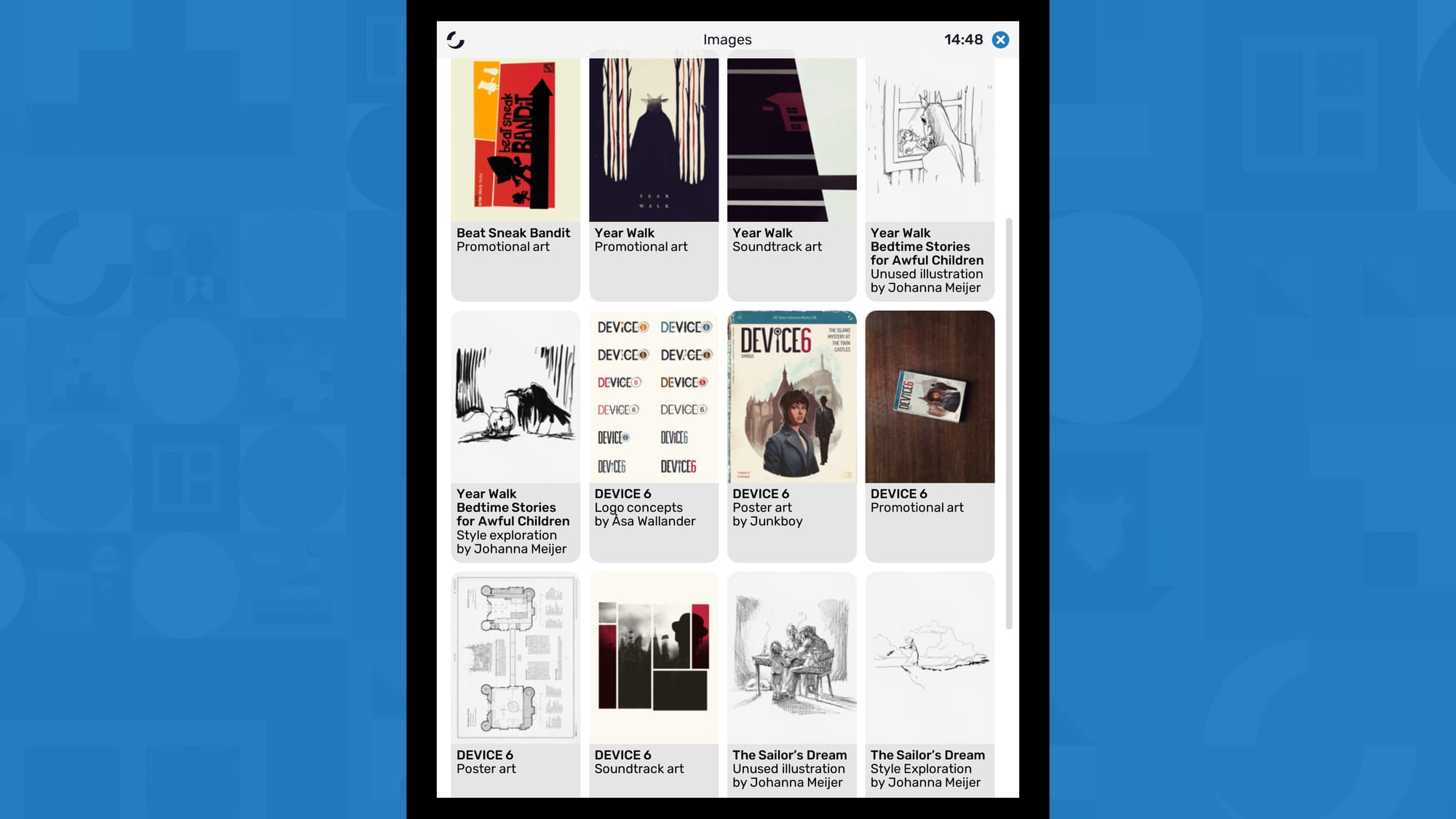

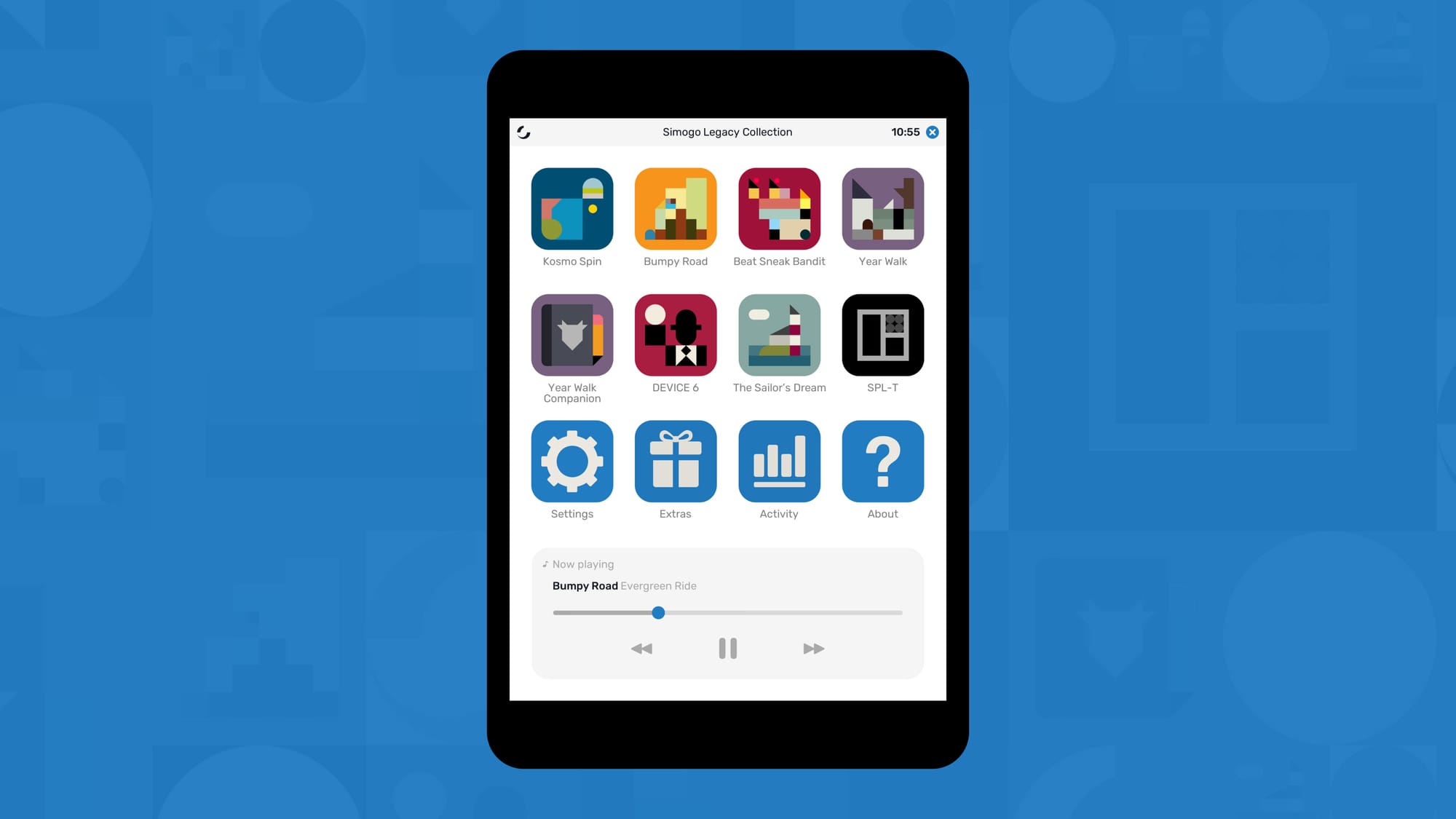

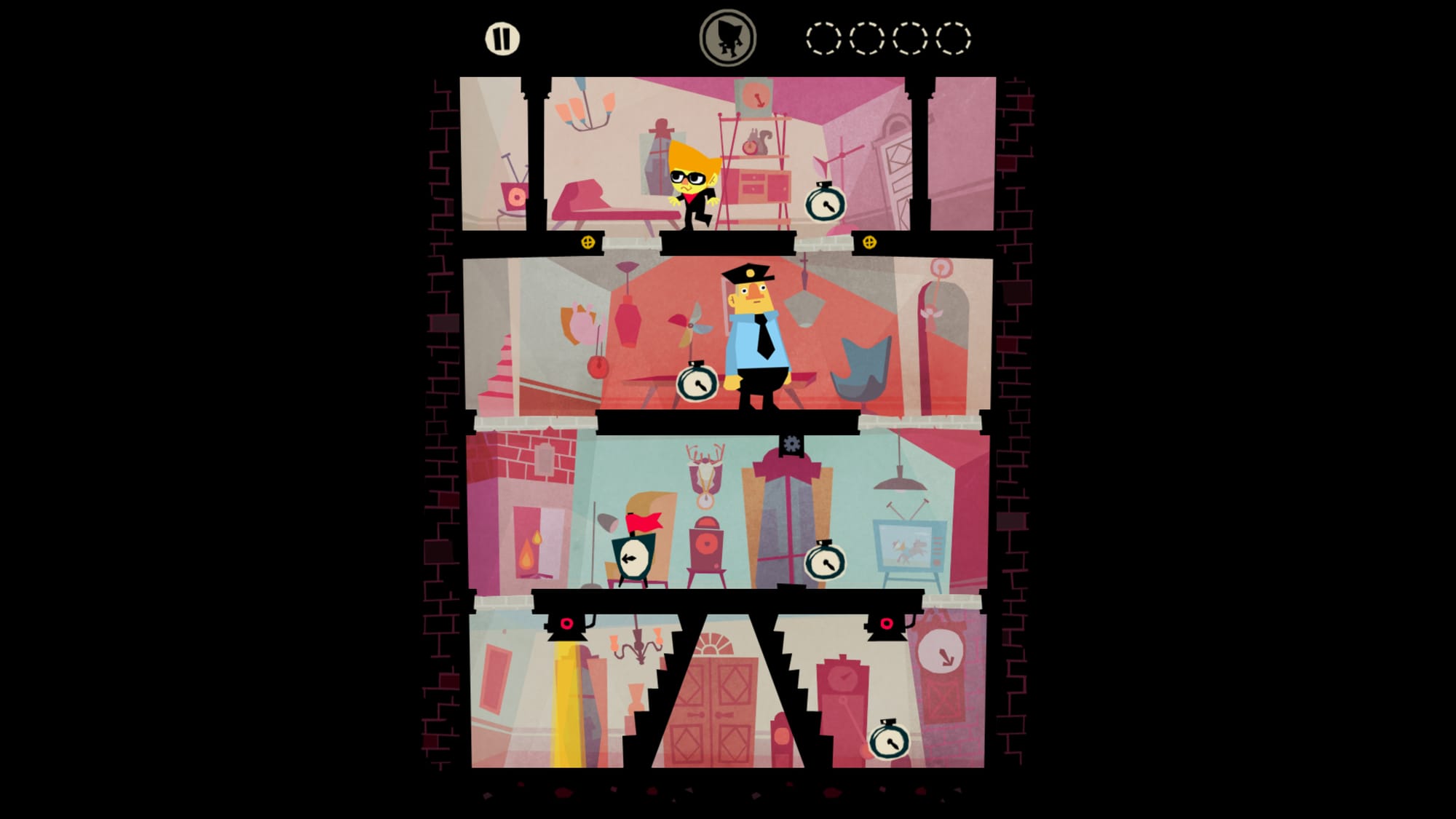

Late last year, Simogo–a creative partnership between Flesser and Gordon Gardebäck—released its Legacy Collection, porting seven iOS games to modern platforms. It may seem quaint, but if you bought an iPhone and were around to launch the App Store in its earliest incarnations, there was an amazingly rich period of game-making in those late aughts. It's understandable that you would want to bring some of that work into a modern context. But this isn't a typical remaster.

I've been thinking about preservation lately, working on a project with the Getty Research Institute. They did something for the 20th anniversary of Disney Concert Hall—Frank Gehry's archive is remarkable, all these scale models and photographs documenting the building's evolution. It made me wonder: is there something about games that doesn't lend itself to that kind of personal archiving the way architecture or graphic design does?

Why Digital Games Are Harder to Preserve Than Physical Art

Flesser acknowledges the paradox. Digital files should be easier to preserve than physical artifacts, yet shifting platforms and proprietary ecosystems make games more ephemeral than sketches or models. Unlike architects who archive scale models, fashion designers who maintain pattern libraries, or musicians' collections of demos, game makers rarely build preservation into their practice. There's less detritus, fewer drawers to store work in. The archive must be actively maintained, or it simply disappears.

What Simogo built addresses their past differently. Flesser and his collaborators created a virtual phone interface for Switch and PC, complete with simulated motion controls and dual-cursor touch mechanics. There's something really poignant about this virtual phone—I played it on the Switch—because I'm "holding" a device that I spent thousands of hours pouring over that no longer exists. You can stretch, pull, pinch, and zoom just as you once did. The Legacy collection preserves the relationship between your hand and the screen of yesteryear, and novelty rushes back in a flood. "For us, how do we make a system where we could show the pixels exactly as they were?" he explains.

The approach stands in deliberate opposition to how most games handle their history. Franchises like Resident Evil and Halo rebuild from the ground up—polishing graphics, modernizing controls—to chase what players remember. The purpose is to evoke an affective response in players–the feeling of what it would have been to boot up a PlayStation or Xbox. Simogo is committed to a different project entirely: preservation as fidelity. "We would always have to say, 'No, actually this needs to be exactly as they were when they released.'" The distinction matters. Remasters capture games as you remember them. Preservation captures them as they are.

What Does It Mean to "Author" a Game?

As a result, you get a unique view into what sustained authorship looks like in games. That continuity matters to me because games struggle with authorship in ways other media don't. Big-budget releases involve hundreds of people coming and going; there's rarely a singular voice. Moreover, games in recent decades have grown to an enormous scale, and unlike film, which has a long history of individual contributions (which is why the Oscars have so many categories), games pass through the hands of hundreds across corporate landscapes that can span years. The history of games is rife with game designers who ship a signature title but fail to build a long career, let alone one that you could identify as distinctly their own.

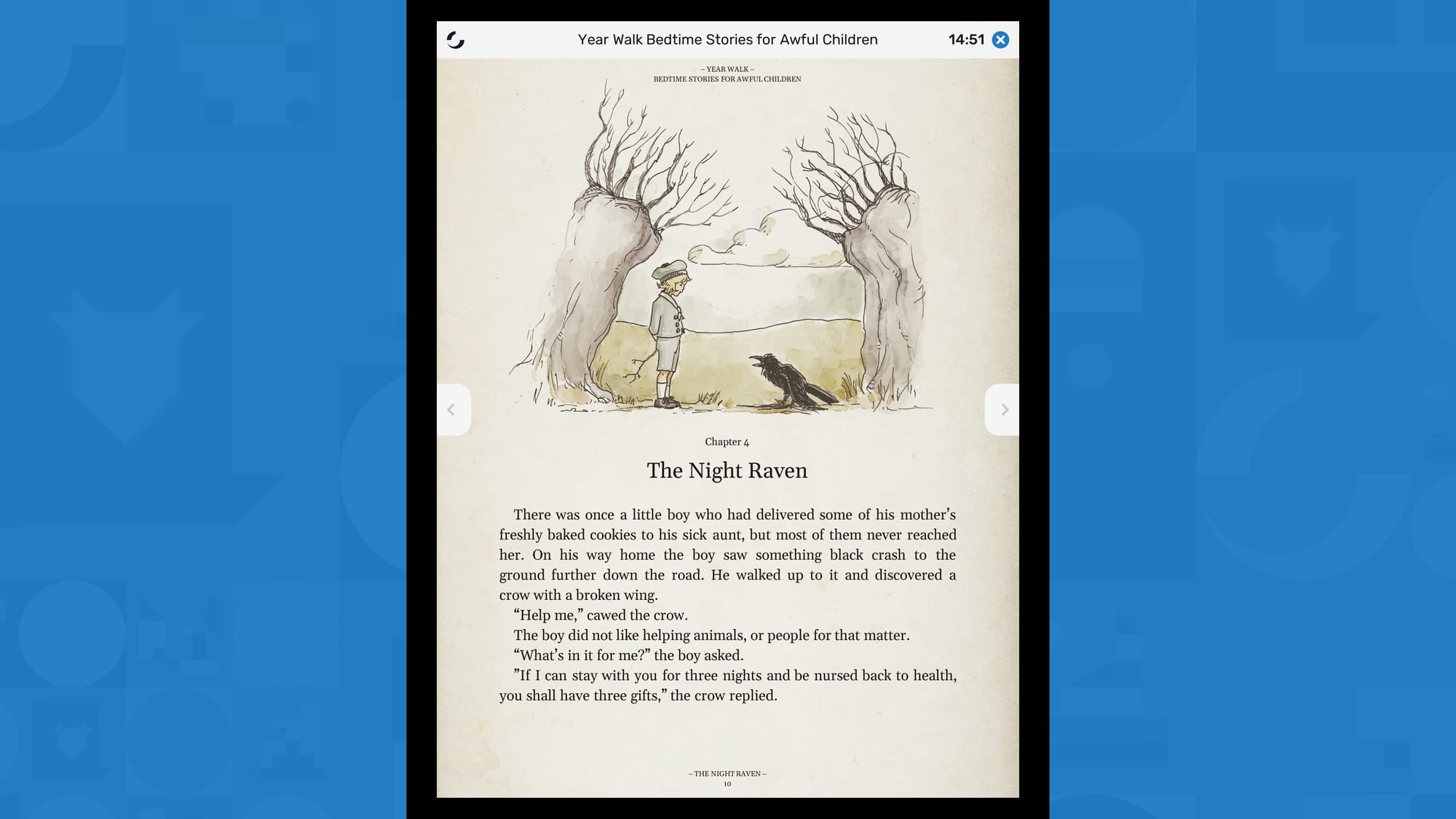

By contrast, Simogo's output has actually slowed as they've matured—seven titles in five years, then two games over the following decade—a dramatic deceleration that reveals a unique DNA that's invisible if you play each game in isolation. Simogo's stable partnership—Flesser and Gordon Gardebäck at the core, with longtime collaborators like composer Daniel Olsén—builds an oeuvre the way bands or filmmakers do. It's a distinct body of work from a team that operates without rigid roles. This flexibility matters as timelines expand and creative stakes shift."Even if you look at the story of Bumpy Road, you sort of see the early themes of death and memories as a recurring thing," Flesser says. "Life, love, and loss basically." The progression from Bumpy Road's pixel-art whimsy to Device 6's typographic architecture to Sailor's Dream's fragmentary atmosphere is the mark of artists stumbling around saying the same thing in different ways.

Can You Preserve Your Work While You're Still Creating?

It's interesting doing this preservation work while you're still in the middle of your creative career as an artist. Many fields have preservationists who handle archival work separately from active production, although that work can still be preserved posthumously. But games don't afford that luxury. Flesser can't just put things in drawers; he has to actively port, rebuild, and maintain. "It's also not entirely preservation because it's just moving it from one digital platform to another," he notes darkly. "But on the other hand, the minute or the hour that it's on PC, it will get pirated, and so it becomes available forever."

Of course, a living archive released at the midpoint of your career gets me feeling some kind of way about my own mortality. I've been looking at games professionally for almost two decades, so looking back in my recent past is welcome but complicated. I remember jumping into Simogo's work almost immediately as a twentysomething, looking to fill my New York City subway rides, desperately listening for the drumbeats in Beat Sneak Bandit, closing my eyes in terror of Year Walk, scrambling to find someone to lend me an iPad to contort the screen in Device 6.

The Legacy Collection arrives at a moment when Flesser's relationship to his younger work has crystallized into simultaneous proximity and distance. "You are sort of embarrassed because they're maybe trying to do more than they could," he says of the early games. "That's laudable because we weren't holding back."

As any type of creative person, your sense of what's good becomes both limited and honed by age—you know what's been done before, so you know what's actually novel. But there's something about being able to make work for your peers. "Games, in many ways, are still toys. They don't have to be, but they can be," Flesser says. "That's not necessarily a bad thing." But when you're 60, trying to make games for someone who's 15, that's going to be much harder. I remember playing Sailor's Dream when it first came out a decade ago. My approach to it is different now, with some life behind me—I have a daughter, my parents are getting older, and a game about losing someone is no longer abstract. Some themes in games are hard to really feel until you've got some life under your belt. The hope as a game maker is that you can continue exploring different expressions of humanity as you experience more of life.

"I've always been slightly obsessed with houses that you can't enter or doors that don't open," Flesser says. "There's so much stuff you can imagine." There's always a mystery with the things we can't quite unlock, the corners of our lives that we can't quite peek around, books unopened, and lives not lived. "The doors are sort of always closed for us when we finish a project," Flesser says. "It's more like, 'Ah, okay, now we don't have to think about this anymore.'"

But it's ok, because someone else will.