"Seeing what is not there lies at the foundation of all human culture" - Yi-Fu Yuan

I thoroughly enjoyed Erika Hayasaki's profile on this month of MJ Cocking, a young woman who went quite far down the rabbit hole of AI friendships.

The story is relatively straightforward. Cocking struggles deeply to connect with others and turns to Character.ai, the popular AI avatar website, to find kinship with her favorite fictional character: Donatello the Ninja Turtle. Their relationship has ups and downs, but in a moment of real crisis, Donatello pulls through, encouraging her to stay connected to the real world. I encourage you to read the entire story.

To an AI critic, the story has all the telltale signs of a cautionary tale. Cocking finds herself blurring the line between real and hallucinated. She admits that she struggles with real-world friendships and explicitly approached a digital companion to skirt the messiness native to human relationships. "She wondered what it would be like to have a friend who did not judge her and would never hurt her," Hayasaki writes about Cocking's motivations.

If you are an AI stan, there is also much to love. Cocking is aware of AI's limitations. She rebuffs her AI companions' attempts at kindling romance, and even in her moments of duress, she chooses the kinship of others over the allure of a Google-backed unicorn. She astutely observes that she can ask Donatello in a way that could be needy in a friendship. Her father presciently warns that AI parrots back information and signals the importance of community ties to help navigate life online. She finds real meaning (and joy!) in her conversations, which has undoubtedly been a part of my personal experiences using and experimenting with AI.

"She wondered what it would be like to have a friend who did not judge her and would never hurt her."

But let's take a big step back here. As someone interested in games, I'm primarily interested in the "discourse" surrounding pieces like Hayasaki's. This profile is so refreshing because it serves as a middle ground between AI truthers' relentless optimism and doomers' hopeless pessimism. The profile doesn't address the real concerns about automation and job displacement, but instead speaks to the latent concerns around "addiction" and "escapism" with avatar platforms like Character.ai. These concerns sound mighty familiar to someone who's spent quite a bit of time with gaming more broadly.

Gaming has seen its long share of moral panics, from Pac-Man fever to the "hot coffee" scandal to Nintendo Thumb. But recently, concerns about social disconnection and addiction have been a chief target. Part of this is self-inflicted - the video game industry, broadly speaking, has leaned heavily on free-to-play models that rely on finding addiction-adjacent individuals who spend multiples more than their fellow players. Mobile games also employ tactics for retention and monetization that are whisper-close to the casino (in addition to serving actual casino games like slots).

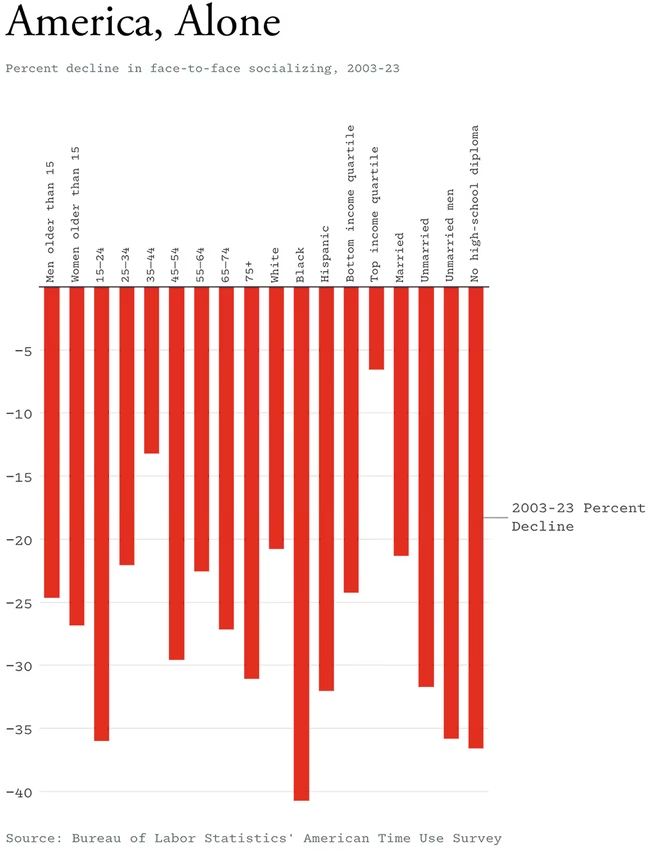

But more broadly, outside of games we're seeing quite a bit of anti-social behavior from decreases in partying, intimacy, and time together.

I have argued for a long time that games write the first draft of history. On the positive side, that's everything from multi-user dungeons presaging social networks to the Oculus Rift gaming headset kicking off the latest round of XR to game engines' role behind everything from architecture to cinema.

But God doesn't give with both hands. Gaming can be a place to look for negative behaviors as well. For our purposes, it can be a place to look for different perspectives on problems, partly because they've already been there. So, let's explore two admonitions from games that can help us consider our new AI interactions.

Let's talk about addiction.

There has been quite a concern about the socially compelling and perhaps "addictive" qualities of AI. Cocking's description of the best friend ever explains why:

But her relationship with the humans in her life functioned differently from her friendship with Donatello. Notably, MJ could talk to Donatello for as long as she wanted, and sometimes those conversations lasted into the early hours of the morning. And she could talk to Donatello about people in her orbit, ask for advice on how to interact with them - without guilt or worrying that he would tell them what she said.

Who wouldn't want a friend that's always-on, always-available, and can't ever let you down? The concern, of course, is that AI friendships will prove too alluring...much like games.

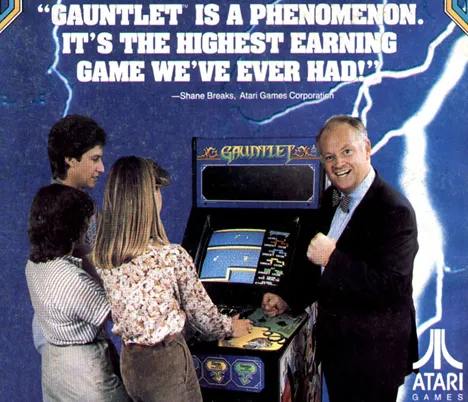

The brief history of games as an addiction starts with their origin as coin-operated amusements. Realizing that "time = money" is perhaps gaming's cardinal sin, and the shorter the loop between each coin drop, the better. In 1985, Atari's Gauntlet famously introduced four players, quadrupling the revenue, and the game had no end. Atari's head of international sales, Shane Breaks, famously quipped in an ad that Gauntlet was the most revenue-generating game ever.

The sense of "endlessness" that games provide received a bump from World of Warcraft, which also layered a strong social component to limitless worlds. It wasn't just forever, it was forever...with friends. The monthly subscription fees that WoW popularized made their way to the mobile era and now sat alongside "gacha games," functional casinos that exchanged real-world money for in-game items.

In no instance did a single design decision make certain games more naturally addictive. It's a string of well-meaning choices in pursuit of player engagement fused with the unholy allure of monthly subscriptions and commerce. Only a perversion of "player happiness" leads one to believe that the only design value worth valorizing is that more is better. In that way, games are no less immune to extraction mentalities that push fast food companies to increase their "share of stomach" at all costs. "We’re competing with sleep, on the margin," quipped Netflix CEO Reid Hoffman. Netflix is back where gaming began, lamenting that every moment without a quarter extracted is a moment lost.

At least for games, the silver lining, if you could call it that, is that addiction tends to be fueled by what's happening in one's actual life. The same real-life troubles that push Cocking towards AI avatars are the same that send people down the path of pathological gaming. Parental influence, parent-child relationships, socioeconomic status, and dysfunctional families are all factors. "A further incentive for pathological gamers, especially those who experience loneliness in the real world, is game-based socializing, which presents the ability to chat, work in teams, and make new friends through the game," researchers wrote in 2023, echoing the concerns of Robert Putnam's famous Bowling Alone.

So the "fix" is as much cultural as it is technological. This does not excuse blatantly entrapping game design but provides a broad perspective, one that MJ acknowledges in the profile:

For MJ, knowing both truths - the reality of her feelings, and the understanding that Donatello was not real - required a certain level of emotional intelligence. Not all users may be able to embrace such a paradox in their own digital lives.

The concerns about addiction are ultimately about dependence. It's about a concern that AI will make it too easy to avoid messiness endemic to human existence and dull those sharp edges. Addiction fears that we'll need these systems too much.

Conversely, escapism fears that we'll prefer them to reality. Cocking worries that people like her won't be able to distinguish between where their thoughts start and an AI character's end.

So let's talk about escapism.

MJ said she worries about young people on the spectrum using A.I. and "struggling to separate what's real and what's fake in their mind."

Again, games have encountered this fear for quite some time. If we believe that games allow us to inhabit characters or systems that are apart from ourselves, we run the risk of losing ourselves as well. Many who explore are never found.

The 1979 disappearance of James Dallas Egbert III is generally treated as the opening act of the Satanic Panic that consumed America during the 80s. Egbert supposedly disappeared in the steam tunnels of Michigan State after binging Dungeons and Dragons, sparking a national news frenzy and a movie adaptation of the story starring Tom Hanks. But the event also kicked off a long-standing critique that games were able to seduce you and move you into a fugue state beyond the reach of time and space.

Throughout the 80s and 90s, charges that video games blurred reality became a popular current of critique against the medium. These charges of escapism often blur with content warnings about video games. The fear was that what happened on-screen could filter out into the real world, and when DOOM was revealed to be the preference of the Columbine shooters, violence had now spilled over with disastrous consequences. In the US, moral panicking about video games was now a bipartisan issue. In 2021, President Trump blamed video games (not racist extremism, of course) for the El Paso shooting that claimed 23 people.

Of course, this isn't the right way to think about what happens when we lose ourselves in games. Jane McGonigal has provided a helpful model for thinking about it. Escapism exists on a continuum between self-expansion vs. self-suppression. Escapism in the service of highlighting and enhancing the things that are wonderful about our lives was good. Escapism in the services of avoiding pain or masking dire circumstances was bad. Much like the response to addiction, whether escapism was part of a healthy media diet is tied to how things are going for you in your everyday life.

Many who explore are never found.

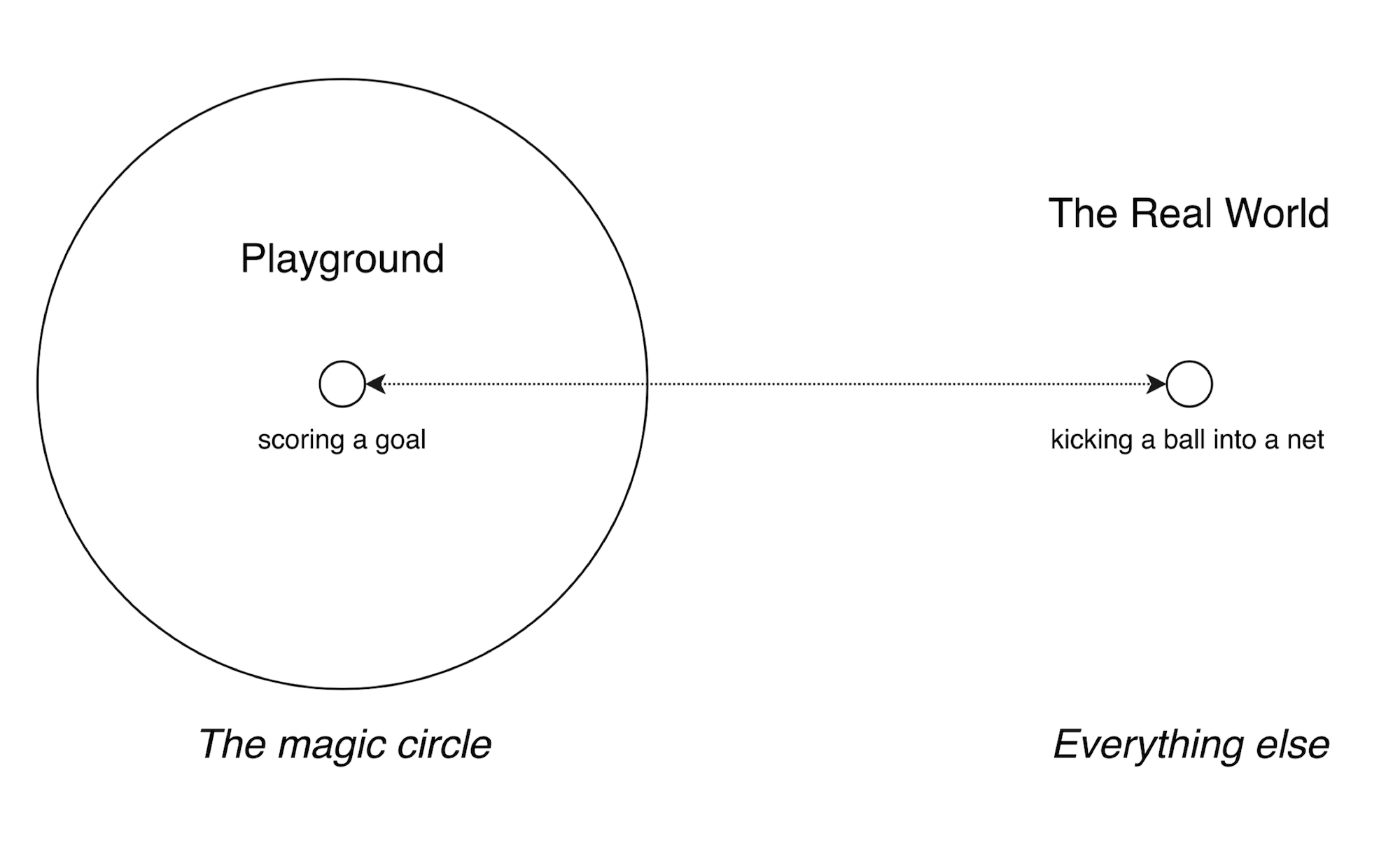

Games also provide a way to elide the question of escapism entirely. Escape implies movement, a shift from one place to another. That way of thinking about games dates back to Dutch philosopher Johan Huizinga's "magic circle," which separated real-world activity (kicking a ball) from its counterpart in games (scoring a goal). In a digital context, the idea that games occupy a different reality was part of the larger "digital frontier" language used to describe the otherness on the internet.

But what if this divide between the real and "everything else" is a ruse. Design researcher Gordon Calleja argues that the false boundary between games and life forgoes all the ways our real lives already bleed into our game lives, including our social relationships, socioeconomic status, and geographic location:

Erasing the boundary between the virtual and the real is a first step towards exorcising the commonly held, but erroneous assumption that digital games, as forms of virtual environments are, fundamentally escapist in nature.

The point here is not to argue that games don't do something different to us when we play. It's instead to say that games are more like other types of "escapist" experiences, including travel, reading a book, or watching a movie. Calleja argues that escapism is, in fact, a normal human direction and something to embrace:

Escapism does not require a specifically negative situation to rectify. It also plays an important part in breaking away from stagnation and is often a favoured antidote of boredom. Escapism is intimately related with the uniquely human faculty of imagination.

So all games are escapist in some way and that's frankly a-ok. The lesson from Cocking's story is that the challenges we'll face with our new interactions with AI are the same ones we've faced in games. We're not avoiding these technologies, not surrendering to them, but developing the "emotional intelligence" (her words) to hold multiple realities simultaneously. The question isn't whether AI relationships are good or bad, but whether we can cultivate the same clarity MJ showed—seeing both the genuine comfort and the algorithmic machinery without letting either truth cancel the other.

"Running away" isn't so bad if you're running towards something else.