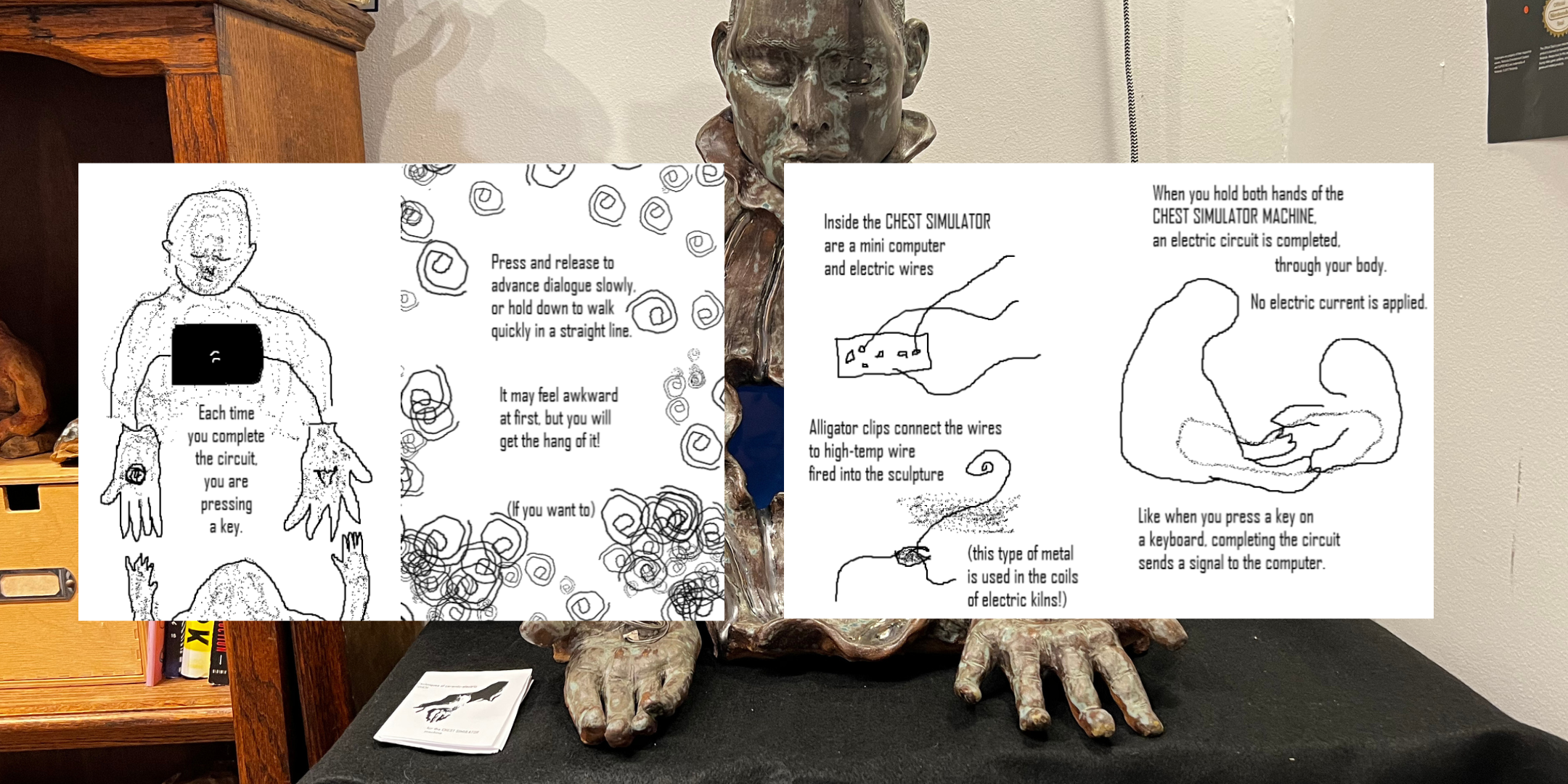

It is one of those usually hot days in Eagle Rock as I pull up to artist Teddy Pozo’s home studio in the foothills of Occidental College, where they teach. A half-body sculpture, molded with clay and fired with high-temperature wire, awaits me, arms outstretched, waiting for my touch to begin.

The sculpture is much smaller than me, my hands eclipse its own, and its lips and mouth closed in meditative contemplation. A shawl collar erupts over the neck, and cybernetic pathways descend over the shoulders. A black and white screen has been placed in the center of a gaping cavity bordered by the clay’s edges, ruffled as if torn. Something escaped, or perhaps something had been removed.

But it's the look of the sculpture that confounds. Is this object a present-day creation? Or is it from 1,000 years ago? The matte glaze gives a dark and mottled appearance from its rudimentary red clay mix and a glaze that shines charcoal-gray. It is a look at the future, but also the past.

Teddy Pozo’s Chest Simulator is a game, a sculpture, a memorial, and a monument. Teddy stands behind me, waiting for me to begin.

Chest Simulator on display at Human Resources in Los Angeles

Raised in Raleigh, Pozo wanted to become an artist out of high school, but didn’t have a portfolio ready and struck out on their AP Art exam. At Swarthmore, Pozo studied physics, but it didn’t resonate. A former partner turned them on to English literature, and they went the self-made major route. Heading into the professional world right after the Great Financial Crisis was daunting, and theory was more alluring. “I was like, what about getting a Ph.D?” Pozo said.

Pozo’s academic training is apparently almost immediate. They take long pauses to meditate on questions, pull in the digressions along the way, and then return to the original question with a renewed interest. It's the mind of a patiently thoughtful person who wants to work through their ideas in dialogue with others.

After arriving at the University of California, Santa Barbara, Pozo was initially turned off by games after an earlier professor said that women didn’t have a “hacker mentality.” But games scholar Daniel Reynolds sent Pozo to play BioShock and Flower to break their routine of noodling through an emulated version of Mother 3 and obsessively reading the webcomic Homestuck.

A turning point for Pozo’s practice was discovering media scholar Laura Marks’ “haptic visuality” concept from her 2000 book The Skin of Film. Applying this idea to film, haptic visuality functions like the sense of touch and can evoke physical memories of smell, touch, and taste. As a game player, these ideas should be familiar to anyone who’s held a controller (although Marks specifically argued that the Power Glove was not what she was talking about). However, for film scholars, this was a novel way to engage with the body in film.

Make some time to watch this. It does contain nudity.

Pozo points to Mona Hatoum’s 1988 video, Measures of Distance, as deeply influential. Hatoum grew up as the child of Palestinian parents living in exile in Beirut. In the short film, she overlaid her mother's scrolling Arabic atop consensual nude photos of her mother. Audio of the two plays simultaneously while she narrates personal correspondence from her mother about displacement and disorientation, peppered with motherly wisdom. It is a short, but highly layered and intimate work. “As a viewer, you’re trying to reach out for the image, but you don’t quite understand what it is,” Pozo said. It’s only a partial text until you bring what you have to it—your vulnerability, inability, or ability to understand it." That a piece of cinema could be interactive this way was a revelation.

Pozo had experimented with making physical games as a child and making “intense” slideshows on Kid Pix Studio, but it wasn’t until dabbling with Twine that they started feeling like games were a real calling. “When you make a Twine game, it’s like you’re already a Twine author,” they joked. While studying for a degree in haptic media, Pozo also found community with their local queer community in Oakland, many of whom were also game designers like Anna Anthropy.

While Pozo was exploring games, two major shifts were happening around them. First, the Nintendo Wii introduced kinesthetic controls in Wiimotes to millions of people and showcased how one’s body could become an integral part of one’s playing experience. Second, there was a groundswell of queer gaming creativity blossoming around Pozo. Anna Anthropy’s 2014 dys4ia and mattie brice’s 2016 empathy machine thrust LGBT game makers into the spotlight. “I wanted to put Marks’ film theory in conversationwith what was happening in games,” Pozo said. “Queer and trans game makers are making haptic work in that it’s about a personal thing and creates personal intimacy that might be uncomfortable for [designer or audience].” Pozo’s research work culminated in a 2018 paper called “Queer Games After Empathy,” a broad overview of these games and the questions they force on players.

Anna Anthropy's Dys4ia (2012)

But visibility put a target on some creators' backs, culminating in Gamergate harassment and abuse. Queer creators were also placed in the impossible position: either express themselves unfiltered or handhold someone “doing the work.” Worse yet, sparked by Chris Milk’s well-received empathy talk that described VR as an “empathy machine” in 2015, the word empathy became a lazy shorthand that corralled any personal work into a milquetoast pen. Poking at the public response to dys4ia, Anthropy later made Anna Anthropy Presents: The Road to Empathy in 2015 at Babycastles in New York to allow players to actually walk a mile in Anthropy’s shoes. “I really don’t think dys4ia was meant to provoke empathy,” Pozo argued. “It’s a WarioWare exploration of medical transition and how hard it is to get access. It was made for trans people (or potentially an egg player on Newgrounds).”

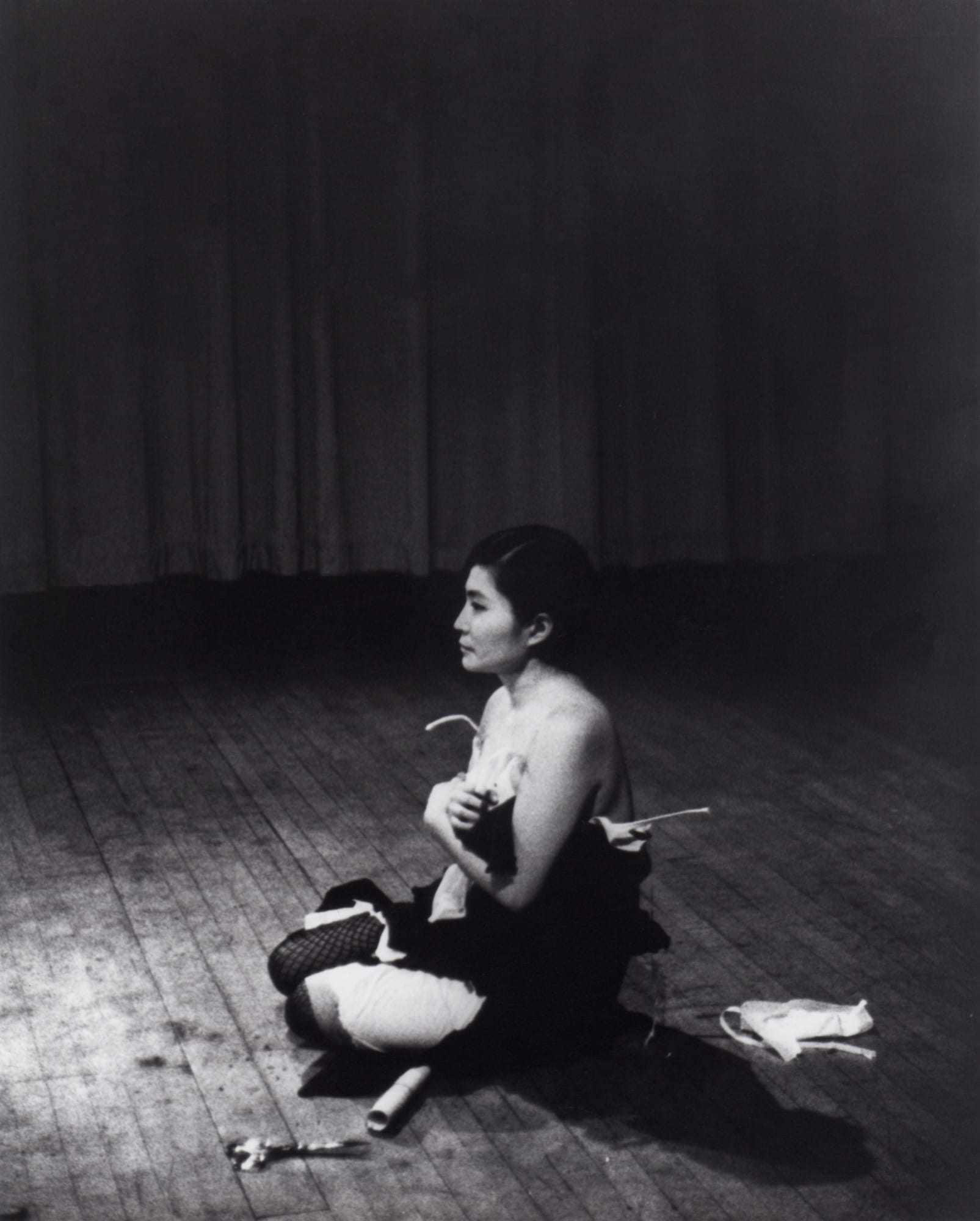

Over the years, Pozo had been interested in games that had bordered on performance. In particular, mattie brice’s empathy machine saw the creator wrapped in conductive tape connected to an Xbox controller via a Makey Makey kit. Then, players were asked to “touch the artist.” Previous feminist artists had endured similar work. Yoko Ono’s Cut Piece asked one to cut fabric from her body, or Marina Abramović's Rhythm 0 (1974) placed 72 objects on a table (including scissors, a gun, honey, a whip) for open-ended audience use. Brice’s work both tapped a rich lineage of interventions and provided a model for Pozo to explore with physical and digital games. With all the theory behind them, Pozo was ready to make something to connect their ideas to a practice. "If trans games are presented by human beings in a human way, will people rise to that occasion?" Pozo said.

Yoko Ono's Cut Piecec (1964) (Photo: Minoru Niizuma) and

Clay as Medium, Surgery as Metaphor

Thankfully, by avoiding the allure of sourdough bread during the pandemic, Pozo rekindled an interest in pottery, which they had pursued as a child. Throwing on a wheel proved difficult, but hand-building felt more natural. Pozo moved to Vermont to teach at Bennington as part of their academic journey and fell in with Katherine Tholl, who’d been a production potter since her teen years.

Pozo had been toying around with the idea of building an arcade machine out of clay, a nod to the bizarre penny arcade machine “The Vibratory Doctor” from the early 20th century. “Why was I so obsessed? What is this weird sex machine that somebody made? ” Pozo wondered, referring to the Doctor’s strange phallic attachment.

Early work was difficult, but there was a pull to working a giant chest out of clay. After showing variations on the body, the work started to come together. Unlike the meticulous and exacting process of code, ceramics is unpredictable and feral. Pozo did tests on coloring that didn’t turn out quite right. “I was reading Frankenstein at the time,” they reflected. “I just needed to accept my creation.”

At the same time, Pozo was in the early stages of planning for top surgery after years of dealing with pain and a binder injury in 2018. As with much trans care in this country, the process was complicated. An initial date was cancelled, and Pozo had to wait alone in Vermont without their partner. Pozo would carry the sculpture to feel the weight, a millstone weighing their past against their future while waiting for their surgery to be rescheduled. “ It was an artifact of a time when I explored the idea of survival,” they said. “I felt sad overall. Formless. Heavy.”

Thankfully, the surgery was a success, and Pozo recovered. After an invitation to read poetry at a virtual gathering called “Communion: Queer & Trans Memorial & Mourning,” Pozo felt a visual novel based on that work would be the proper game structure for the work.

With the sculpture concept complete, the last piece created the interactive tissue to bring it to life. Instead of attaching wiring to the piece, Pozo found that high-temperature wire, the same type found inside a kiln, was an excellent way to connect a circuit–an apparent first for games. You hold hands with the sculpture to advance the plot and bring the visual novel to life. The game had been initially planned as something more graphically complex, but after so much work had gone into constructing its container, Pozo planned something more austere.

Chest Simulator shuttles you through the poem and through Pozo’s process. “Eulogy for old friends” starts with Pozo’s earliest memories of puberty, the anxiety and shame of prying eyes, and the realization that “for me to live, you had to die,” Pozo wrote. Each touch of the hands moves you further upward, through a desert highway, through abstract forms, and finally to a friendly, knowing avatar. The work is short–about ten minutes–but propulsive and intense.

Opening sequence from Chest Simulator.

The context is what makes the Chest Simulator so different. First, you are holding hands, mapping your movements over the sculpture’s copper wiring to advance each page. Consider whose hands you hold–a parent, a partner, a child. Perhaps you say a prayer at dinner with others. But in general, the act of hand-holding is a rare gift. Games have attempted to simulate the intimacy (notably 2001’s Ico), but it’s quite different when you can fill the contours of a hand rising to meet yours, even if they are cast bronze.

In May this year, Touch Praxis's research project invited Pozo to show the work at Human Resources in Los Angeles. In contrast to other games shown in a fine arts context, Chest Simulator was the only game alongside other tactile works of “fleshy proximities, felt theory and porous encounters.” Nestled in an alcove at an old movie theatre and sharing space with other work players, moved in and out of the work. Some couldn’t finish. One person asked for a hug. “They ended up touching my body after all,” Pozo joked.

Although our bodies change over time, clay does not. There’s a permanence to clay that provides a scaffolding for the messiness of human experience. Chest Simulator is part of a larger imaginative universe Pozo calls “Game Boys of the Earth,” an ongoing project to merge clay bodies with digital ones. The next work, Sacrifice, is enormous, over six feet tall, with another cavity for players to lean into. “It was designed for my body proportions, so you need to figure it out,” Teddy said. “I tell people it’s not an Apple product, so it’s not immediately supposed to work for everyone.”

Chest Simulator has opened a new avenue for Pozo in their approach to game design. “A lot of times people will make the game design first and then find what will display it,” Pozo said. “I've been experimenting with making the sculpture first and then making the game about the sculpture.”

Months before their show at Human Resources, Pozo had to evacuate from the Eaton Fires. As they were undergoing the grueling process of deciding what to take, there was some comfort that everything burned; the sculpture had already endured a long blast of the kiln. A wildfire likely wouldn’t be enough to tear down something so important. “Will it still exist?” Pozo thought. “I didn't know, but clay things just last.”