What happens when artificial intelligence becomes a site for reimagining collective consciousness? For Mumbai-based artist (and newly-minted UCLA professor) Sahej Rahal, game engines offer a space to interrogate the very foundations of intelligence, hierarchy, and what it means to be human. Working across sculpture, performance, and interactive media, Rahal creates speculative creatures and AI simulations that challenge Western notions of individual consciousness while drawing from centuries-old Indian philosophical traditions.

His practice unfolds like an ongoing mythology, with each work—whether physical sculpture or digital simulation—adding another layer to a narrative that spans archaeological time, mystical poetry, and contemporary political critique. Through projects like Anhad, an AI musical instrument that listens indefinitely to the world's sounds, and DMT, a cooperative game where multiple players control a single creature, Rahal constructs alternatives to the hierarchical thinking that structures both ancient caste systems and modern AI development.

Here, we speak with Rahal about archaeology as methodology, why he's drawn to non-human forms, and how game engines can become spaces for collective intelligence that transcends individual agency.

Jamin Warren: Can you tell me a little bit about your personal background? Your interdisciplinary approach drew me to your work, so tell me about your background in game-making as part of your practice.

Sahej Rahal:. My practice is this one story that's unfolding in an infinite kind of iteration. With each work, each object, image, performance becomes one aspect that's added to the story—one more motif or tone to that unfolding. The reason why I decided to do this in art school was that I wanted to get around explaining what I'm doing while I'm doing it. All these created things are essentially toys to play with, and it's also an invitation to the audience to find those answers for themselves. What do they think these things can mean as that one act goes on?

It's led me to interact with archaeologists, who do the exact same thing. It’s called terminus post quem, which means there's this limit, this temporal limit that we have, and an object might lie somewhere around that limit, but we don't know. An example of this would be if they were to find something closer to our present day in an archaeological site that is 5,000 years old, because someone might have ended up dropping something there at some point. This actually happened—Mortimer Wheeler, who's supposed to have discovered the Mohenjo-daro and Harappa archaeological sites, would conduct archaeology with dynamite. So things kind of got moved around a bit.

This is not particular to archaeology. Psychoanalysts have a word for it as well, where they use words like cryptogenic or xenogenetic, where they say that we don't know where this came from. The origins are cloaked in mystery and things like that. These are heavy words to say that we have no clue. I've latched onto this while exploring even ideas of AI—you see that sort of rhetoric being used for emergent behavior, where the mind of the machine somehow just arises. I've been looking for those markers, those blind spots, to trace narrative and trace this narrative trajectory through. That's essentially how the work has evolved.

Presently, it has brought me to AI simulations and video games, which have been the presence of these forms of machine intelligence and the discourse around what it means to be human. What it means to be intelligent, what it means to be, in a fundamental sense, alive. And then looking at the blind spots of that. That's generally been my journey.

Rahal's ANCESTORS merged speculative fiction with archaeological post-reality. Artifacts and skeletal remains tell a story of a civilization yet to come.

Warren: I hadn't thought about it in that way. The objects that you have have this feel of something from the present or the near future, but obscured by the past through patina, or they exist there. Obviously, that is a challenge for archaeologists and anthropologists—how to contextualize things that they find and put them in context, and you are creating objects that are connected to this larger mythology. When someone interacts with any of your work, that's part of this broader story.

I guess if something of yours is buried, maybe 1,000 years from now, someone will be tasked with trying to figure out: Was this something that people used in the year 2024, or perhaps it was an object that was created by an artist? Your approach makes a lot of sense in terms of what games can offer as a way to both extend your existing mythology, but also, from a sculptural standpoint, a way to create these things that don't quite fit in any particular place in time, except outside of the myth world that you've created for them.

As a more practical question in terms of getting started with game engines: When did you start tinkering with game engines as a way to express your work? And then we can talk about the two works that we'll be covering today—DMT and Anhad.

Rahal: I actually started—I have a background in programming. I was preparing to be a computer engineer at one point, and then went to art school. In 2017, I was at this residency in Stuttgart called Schloss Solitude. I also met these programmers over there who basically told me about Unity. At that time, my language was C#, so I just picked it up very quickly. I was working with Unity up until the pandemic, and then I came across Unreal. And I was like, OK, let's start using this thing, because this is better.

I loved all the procedural stuff, as well as the more experimental stuff that Unity can do from this guy's GitHub page called Keijiro Takahashi. He put up a bunch of his code on his GitHub, and I was just studying that.

Warren: You want to find the instrument that works best for where you are today, and that can change over time. Companies are companies, and they have different affordances and biases, so you have to make sure those line up with what you actually want to and are able to do.

Rahal: Yeah, for sure.

Warren: Well, I'd like to introduce two of your works. Can you tell us a little bit about Anhad and DMT?

Rahal: I'll start with Anhad. Anhad is an AI simulation, or another way to think about it is like it's a musical instrument that you can sing with. The word anhad means unscalable. It comes from this couplet by the 15th-century poet Kabir. Essentially, what Kabir says is—the translation of the couplet is: "Limits are all they speak of, yet they dare not cross them. I shall meet you on the playground beyond those limits."

Kabir specifically, in that couplet, is talking about the limits of language, the limits of becoming human that we impose on ourselves through naming things, through saying "I am man, this is world," and then distancing ourselves from that world, and at the same time distancing ourselves from other human beings as well.

This is a tradition that is followed across the oral tradition of Sufi poetry in India. It's not just Sufi poetry. It's the syncretic, reformist movement that has followed since the 15th century, of which Kabir is a product. You also see faith practices coming out of that reform movement, both in the North of India, all the way up to Kashmir, and in the south of India. There's a rejection of these structures, these hegemonies that have been imposed on people, the primary one being the caste system.

The reason why I'm talking about all of this—the caste system is essentially premised on this myth that there is a man at the center of the universe, and his cosmic anatomy of this Purusha man is essentially supplanted onto society, and society is divided in that way. So this man's head gives rise to the higher caste of Brahmins. His torso and shoulders give rise to the Kshatriya warrior caste. His thighs give rise to the merchant caste, and his feet give rise to the Shudra, the lowest caste. Everyone who does not fit into this cosmic hierarchy does not belong in society.

There is this figure, this human figure that defines itself by what it is not, by exclusions. And it also creates a hierarchy between the mind and the limb, the foot, and then everything that arises from the mind. The Brahmin is essentially the top of the social food chain.

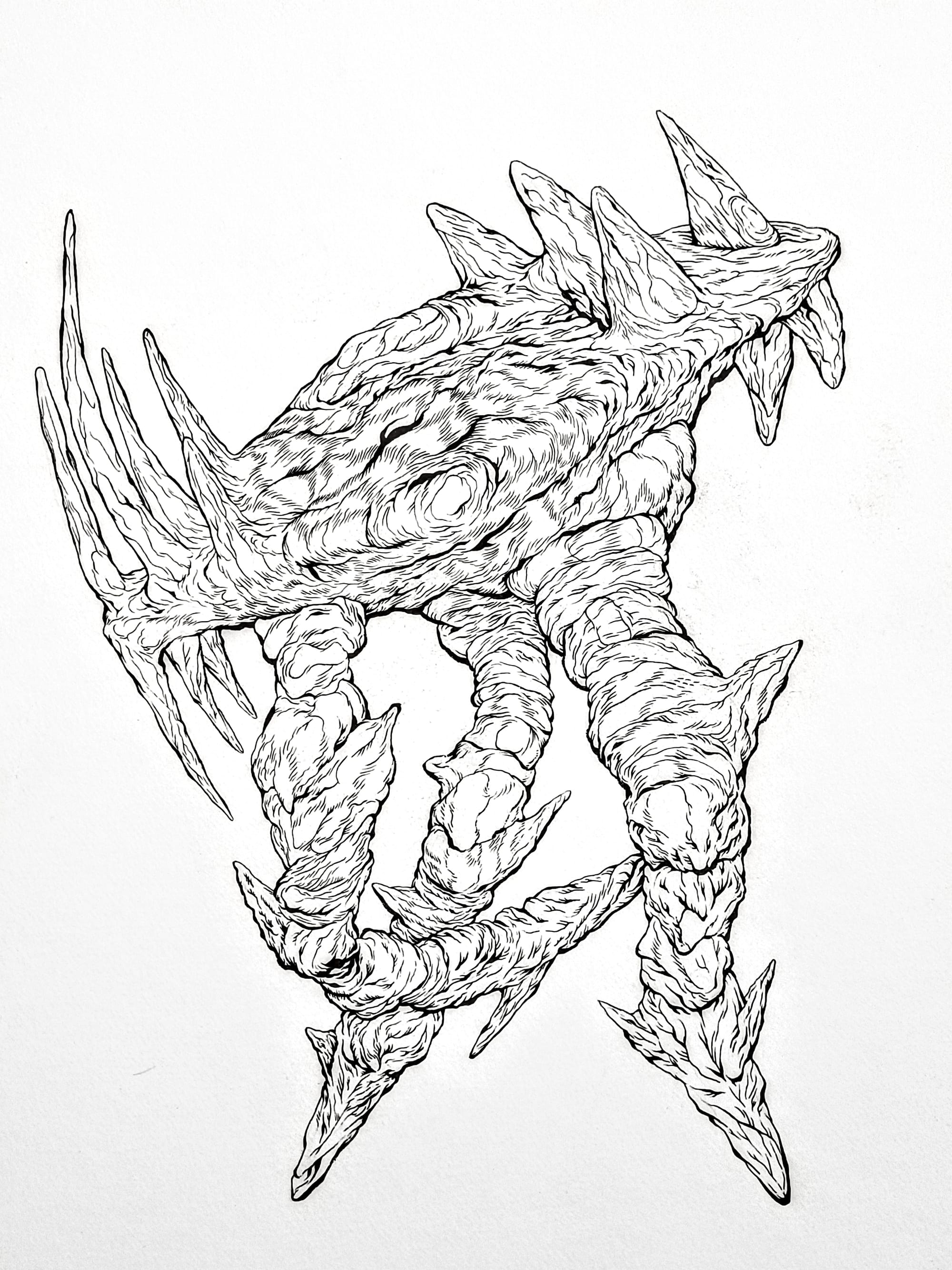

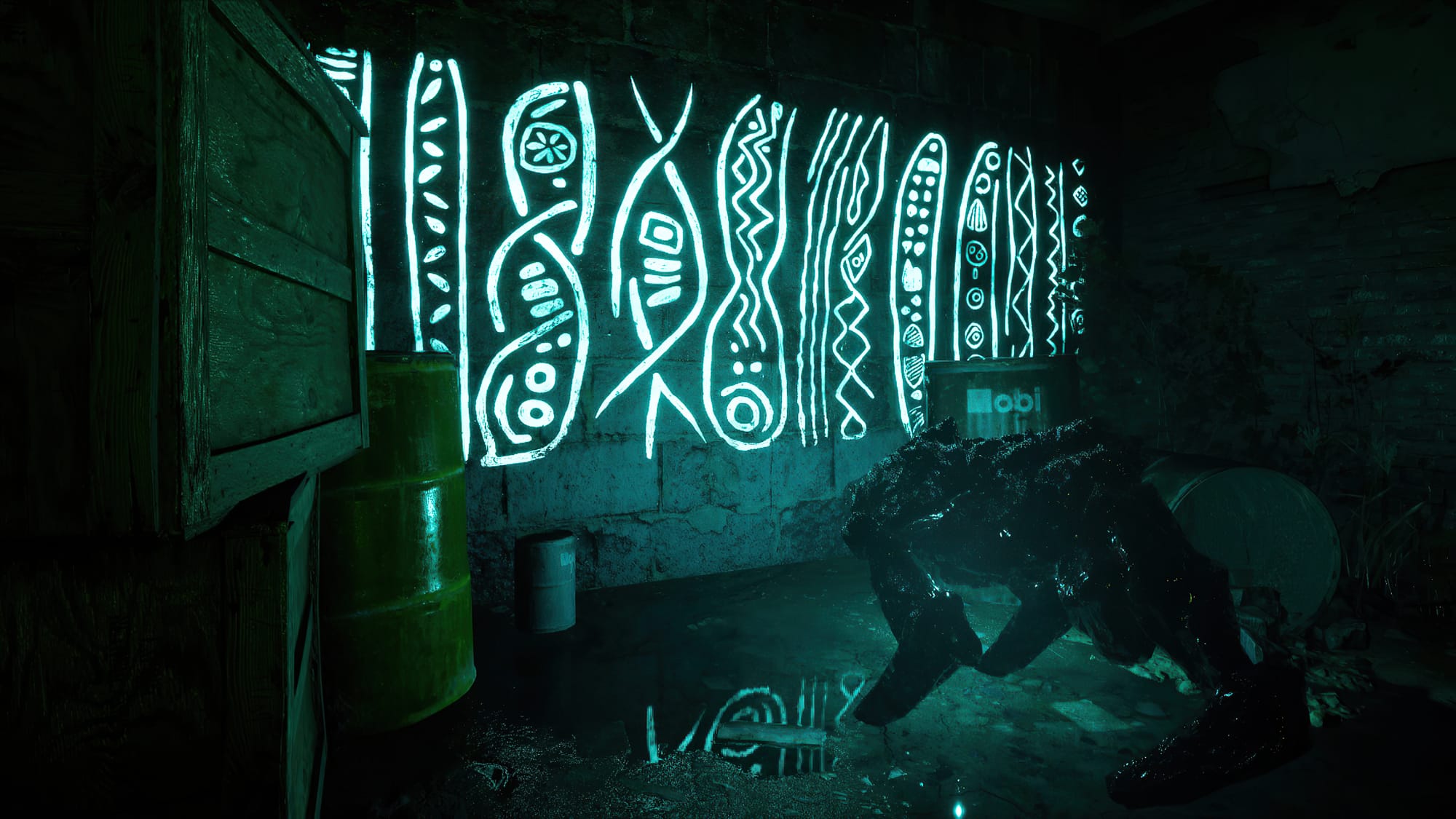

Game footage and sculptures for Anhad

We saw very material forms of this in the last 10 years of the current government, where you saw these very Cold War era laws being brought into [Indian] parliament and being passed as the Citizenship Amendment Act and the National Register of Citizenship. These primarily targeted Muslims who don't belong in this cosmic hierarchy, and saying that they are not Indian.

You have a version of this playing out in Europe as well. Following the tradition of the Enlightenment, where Descartes said, "I think, therefore I am," he essentially places the mind before the body, which is symptomatic of sensorial impulses. The body only exists because it feels things. But whereas the mind perceives and thinks itself and by extension of that act of perception and interpretation, it is conceiving of the world. Everything else is secondary—the world, the body—all of it lies outside.

Killscreen is a labor of love and home to independent game-making practice. Consider supporting for more coverage of the future of interdisciplinary play.

I bring this all up because Anhad proposes an alternative to this cosmic hierarchy and this linguistic hierarchy. Essentially, this form of man, which has led to the world that we find ourselves in, is this form of being that allows for the world that we find ourselves in. What I mean by this is that in Anhad, you have this tripod creature, and each bone of that creature has a script attached to it that is acting like a proto-mind. And as it's moving, it's picking up audio feedback through the computer's microphone. So essentially, what you have is the mind, the limb, and the ear—this organ is all enmeshed so that hierarchy doesn't exist, and this allows for essentially a form.

Now, the way the program itself sings as the creature is moving through this environment, I've taken my friend Niyati’s song and broken it up into an array that is getting fired as the creature moves through the environment, depending on what you could call its mood, essentially.

And now, hypothetically speaking, if someone were to let the program run, and human civilization were to collapse tomorrow, because this program is listening to all sound undifferentiated, it would continue to listen till the last sounds of the universe are heard. So it's this kind of gesture towards something that could conceivably outlast us, in a way.

Why the song? So, in the tradition of Kabir, there's Harinder Singh who says that humankind has separated itself through language. Before the world that we find ourselves in, there is a song that is resonating across space and time. It's just continuing, and all forms of being are moving with that song.

Now, man has distanced himself from that song. The birds remember this song because, for birds, the morning call of the bird—the morning song—is actually a kind of roll call to say that they made it through the night. They express desire through music. The task of all art, essentially, is to return to that song, in some way, and make inroads to that song.

Now, with AI programs, we have somehow separated language from humans as well. Now, language can supposedly create itself, and humans are essentially purely removed. We are inconsequential to this larger endeavor. Now, I feel this is obviously incredibly anti-humanist, or nihilistic.

And what are the other conceptions of this post-human sort of entity that we can conceive of? Anhar is essentially one gesture towards that conversation. What other forms of being beyond the human can we put together and converse with essentially?

Warren: Birds have what is called convergent evolution, where birds and humans both developed speech patterns, but with completely different systems. And it does make you wonder about artificial intelligence, that there is so much that we don't understand. We don't understand how these large language models actually function. We know they provide the outputs that we want, but we don't really understand the pathways.

Rahal: Right.

Warren: With DMT, I’m guessing the Metal Gear franchise and Hideo Kojima are an inspiration for you. I think there's often a challenge with world-building type projects that they often forget what makes games games. Tell us a little bit about the DMT.

DMT. The full name is Distributed Mind Test. I wanted to make a video game because I thought Death Stranding was incredible—it really got me through the pandemic.

DMT is a cooperative multiplayer game where everyone's controlling that creature together at the same time, and it can have up to eight controllers. The way this works is everyone has access to all the creature's movements and abilities simultaneously. So it's a game of total discovery—you have complete knowledge of what you can or can't do, but it's also a game of constraints. The constraints here are your fellow players and the fact that you have no access to their inner selves. If you and I are playing, and you move forward and I move right, then the creature would move diagonally.

There's also a resource pool that governs the creature's abilities. It can only perform certain abilities if it has that resource pool, and you have to wait for it to generate. The echolocation call, sprinting, the bionic light that reveals things in the map—all of these are governed by that resource pool. So we need to negotiate in terms of what we're going to do next.

There's a narrative that binds all of this together. Human society has collapsed or vanished for some reason, and they've left behind these memory boxes with audio logs that narrate what happened, what led to that vanishing—spoiler alert, it's capitalism! In the wake of that exit, you have these strange, other creatures inhabiting the world. Some of them are oceanic creatures that have now learned how to mutate into creatures that can live outside of water. You'll find squids, mutated manta rays. There's also a whale somewhere in the game that you have to free, and that triggers certain things.

Essentially, there are all these bits and pieces in this playground, and people get to put together their own headcanon about what's going on. At the same time, the game, on a more conceptual level, was asking: What does it mean to have a thought, to be intelligent, to be thinking beings? What is the fundamental texture of that when we say the word intelligence?

After having interactions with people who were designing AI programs for startups, I realized that this idea of intelligence—of machine intelligence and intelligence at large—is up for grabs. There's no consensus on it. I was seeing that certain narratives were being framed around it, and I wanted to have that conversation through gameplay.

What happens when you're playing the game is that you and I become these fractured thought impulses that are embodied within this creature, and we're guiding its movements. We could be contending with each other, or we could be working in concert and moving through the world. This allows for certain emergent gameplay to take place.

One thing I saw across the board in playtests—I took it to the India Game Developer Conference here in Hyderabad, where I got a chance to share the game with competitive gamers, artist friends, game designers, people I'd reached out to on the internet. The game was also part of the Moving Image Biennale, so it was in a proper art setting, in a gallery where people could engage with it as an installation.

One element that emerged was that you see people playing by handing over control—parts of the control—to whoever they're playing with. Between themselves, they'll decide one person's going to control the camera, one person is going to control the abilities. But that also gets complicated, because the camera also has an influence on the movement, the abilities also have an influence on the way the camera works, on what gets seen or not seen through the camera.

So it was creating these feedback loops, but at the same time, this handing over of control was essentially an act of surrender. Instead of holding on to more power or more agency, they're giving it over, bringing it into this shared space where people are saying, "OK, we will arrive at a consensus based on all these modes of action that are available to us, all this hierarchy of thoughts that is available, this area of possibilities."

This is the fundamental thing that I was hoping could be possible. I don't think I have an answer myself—that's why the game is called a test. But can we think of democracy at large as this cognitive act, where rather than framing it as something where I have agency because I vote, I have shared agency, which I submit to, surrender to? You see this act of surrender in all forms of radical organization, from Sufi cults to rebel collectives in Seattle, all forms of decentralized action, where it's almost like a call and response game. That was largely the framework of the game, and it was really fun to put together.

Warren: You use the word collective intelligence. That seems to be the connective tissue between these two projects. Herndon has advocated for renaming artificial intelligence "collective intelligence" instead. For the technologists that are building these systems, there's a desire to sublimate the human part, to sort of make it seem much more magical than perhaps it actually is. It is built on top of eons of human intelligence, all these things that are written down, remembered.

And there's actually something wonderful about that, about having a system, a machine, that kind of takes all of these things together and then gives you responses based on how other people have responded. And there's something that is much more humanizing about that, especially in your context, where your inputs are significantly smaller. They're based on humans in both instances, a more finite set of humans, and then having them sort of create, generate. Whether it's through this infinite song that gets generated through this interaction, or through the movement of these individual characters. So it is interesting to see you situate your work both in terms of contemporary conversations around what's happening with artificial intelligence, but also finding ways to use that for your own particular practice.

One question I have for you is some of the reasons why you ended up in games—you do have a focus on non-human creatures, right? These are both non-human in the sense that they don't visibly share the characteristics, which is also interesting for you working in game engines where there is so much primacy that's placed on having human characters. Unreal when they're demoing—the demos are textures, but a lot of times it's like, "Oh, look at the simulacra of human face.” You can see the textures, the micro-movements that your face, those subliminal micro-movements that are undetectable for the human eye. Can you tell me a little bit about how using speculative systems, also with non-human characters, gives you the ability to interrogate and critique what's happening in the real world? I'd love to explore that a little bit further with you.

Rahal: Actually, this was one reason why I was interested in Unreal as well. Because you can get that very seductive graphical fidelity, right? I'm completely dazzled by it myself. And I enjoy it, I need that kind of graphical "Oh, wow, this is how real this is," right? But it is also antithetical to the way a documentary works. So a documentary image, or even the cinematic image, is bringing you into the space of suspension of disbelief and telling you it is the truth.

Even documentary filmmakers know it’s construct, right? It's a construct in the sense, on a very grammatical level as well, but also conceptually as well. I'm not saying the bias goes one way or the other, but it is a human that constructing that image. Whereas these kind of graphical images, these high intensity, 4K-rendered, heavy textured images that these programs are able to generate are working on the principle of "Check this against reality." They tell you to go look at what the real world and almost draw you into that uncanny valley, closer and closer and closer, right? Its seductive nature lies in that double take, as opposed to saying, like documentary, "I am pure fiction, but you will still come in. You will still follow."

Unreal Engine's MetaHuman 5.6

So now, the kind of creatures that you see in the game are versions of real-life sculptures that I've created. I started building these forms back in 2011. The idea was I was picking up found objects and then just kind of putting them together using geofoam, glue, and concrete and stuff like that. These mutant creatures have somehow arisen from the detritus that we find ourselves with.

Bombay has a lot of found objects. I was putting these things together, and then kind of making toys and instruments that you could actually play, and using them in performances. These programs became a way to create virtual renditions where they become more participatory, where they start shaping the way this larger narrative of this mythology is unfolding.

Why do I make those forms that way? I don't know. I'm just kind of drawn to that creepy thing.

Warren: We're on the back of a really seminal election in your country. This is a conversation I've had with other Indian artists working with game-based art or in speculative contexts. Could you tell me about the contemporary political context and how it's impacted the way you think about your usage of game-based art? It feels like the conditions are ripe for you to generate something unique to your context, which is always interesting to me, but also a way to talk about some of the things happening in India for folks who maybe aren't following the news in your country, not just for game-based art, but also for art at large.

Rahal: I feel like in India there's not a moral vacuum, but an immense lack of imagination more than anything else. It feels like some really well-known luminaries have literally bent their knee and done exhibitions for Modi's podcast—apparently for the 100th episode he was at the National Gallery of Modern Art in Delhi. It's ridiculous. There's obviously a corporate takeover. There's this museum that [billionaire Mukesh] Ambani has set up, which looks like a Death Star has landed in the middle of Bombay. It's got nothing to do with the space it occupies outside—it could literally be somewhere in Dubai.

A chipper video that belies the context.

This comes in line with the institutional coups that the ruling party has been trying to orchestrate for the last 10 years, and we're seeing a spillover in the arts as well. But at the same time, I feel like there are other ways you can still work. The question remains: if you're going to put that much time and the kind of setup you need for, say, a new media exhibition, most of the spaces available are very close to money that I find problematic personally. But no one's going to stop you from sharing something online—just share things, send them. I feel like that might change for a time. In fact, I'm confident it will change. But there's a whole generation of artists who have grown up with the internet, who have built entire practices online.

There's this really brilliant young artist named Vinit Dharia, We were working together in a workshop where he created his own AI generator that can generate images and faces—it had a character creator that would give you a full backstory and everything. But what's really amazing is the economy of how he works. He built this entire thing using Google Docs because his computer had crashed, and he built it over the course of two months using Google Docs. As you engage with the project, you see how deterministic this thing is—how these programs that claim to be magic boxes are completely unraveled in this really beautiful, sharp and poetic set of code.

There are so many more artists like that now. Google Docs doesn't really need a museum around it, and an Excel sheet doesn't need institutional funding, right? There are ways you can work in spite of the systems we find ourselves in.

This interview was conducted in 2024 as a live talk. It has been edited for style and grammar.

![Event[0] will break your humanity](/content/images/size/w800/previously/wp-content/uploads/sites/5/2016/09/event0.jpg)