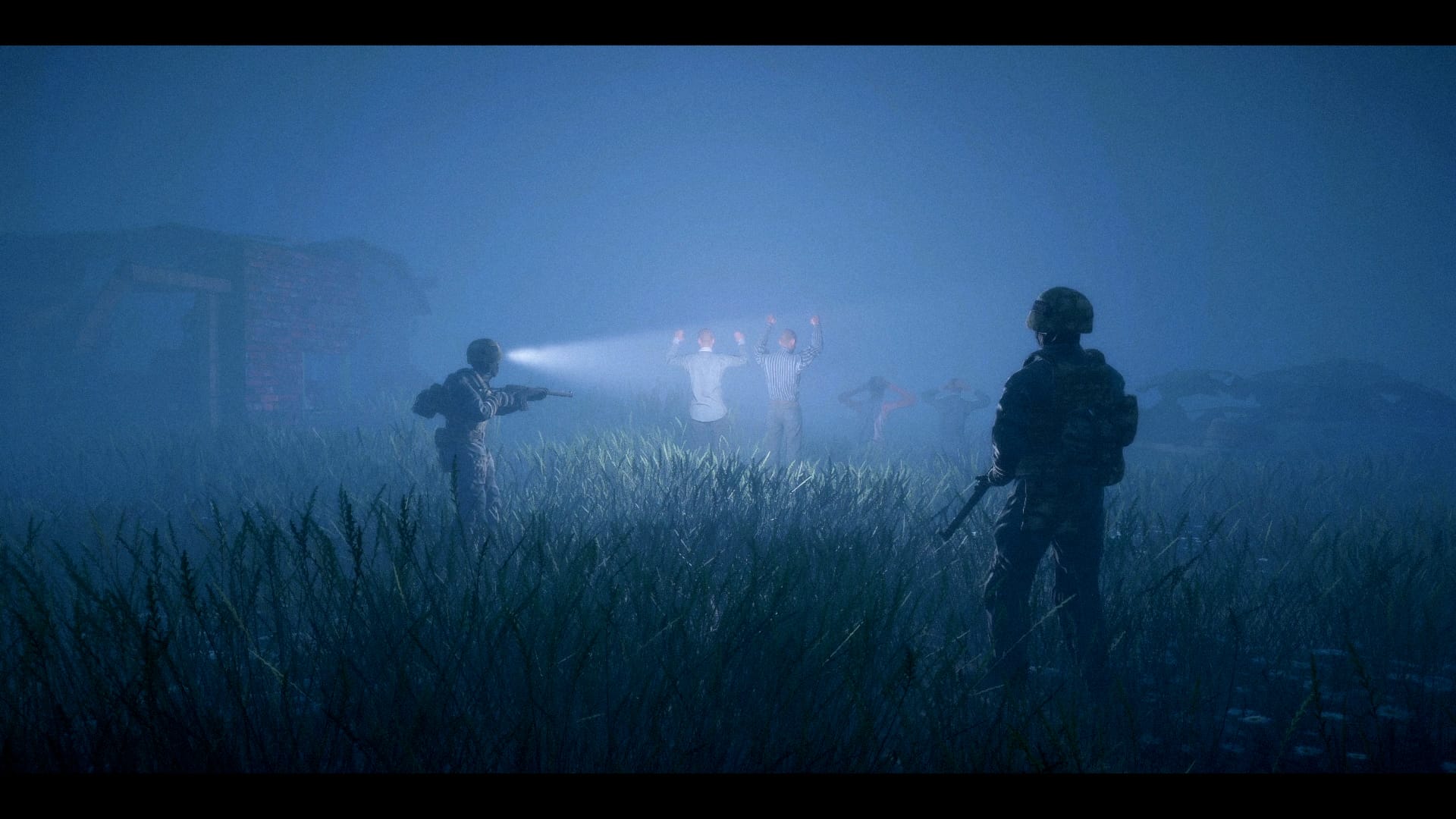

I, a lone dog, wander through a forest and then a field, choked with haze and ruin. Bullets whizz overhead, and I crane my head towards the sound of shouts and cries. I can do nothing, so I move on.

I, a lone dog, cross paths with someone desperately trying to escape. They are as silent as I am as they pass under a fence. I can do nothing, so I move on.

I, a lone dog, pass by a military van, listlessly inspect the soldier inside, and continue my trek. There is a clearing, and beneath it lies a terrible secret. I can do nothing, so I move on.

The video game industry, a $200 billion engine of violence and virtual conquest, has long placed the most powerful weapons imaginable in the player's hands. But Alan Kwan's new title, Scent, offers no firepower—just a lone dog wandering a desolate war zone. "The whole concept of this project is about being a witness without power," the art professor, filmmaker, and game designer said about his 2025 Tribeca Festival premiere. "In most commercial games, you have superhuman abilities, but for most of my games, especially this game, the main character is very fragile."

The key for Kwan is the feeling of impotence when we are so exposed to violence and can do so little. Scent is an audacious and drastic break from the "war in games" genre. You play as the titular dog, wandering an unnamed war-town city, and collecting the souls of those who have fallen. Almost nothing is known about the victims, the perpetrator, or the location. You are simply moving through this melange of violence and suffering, unable to do a blessed thing. "You just walk, witness, and hide," Kwan explained dispassionately.

A sad precondition of living in 2025 is that war is once again a principal anxiety. After the horrors of the early 20th century and the construction of international institutions, the sinews of the global order are fraying. This isn't simply about the United States' making its authoritarian tendencies explicit and supporting them abroad—war, conflict, and genocide now stretch from Ukraine to Gaza to Sudan. According to the Global Peace Index, global peacefulness has declined over the last nearly 20 years. So, it's not just you, and it's not just your feed.

So, how do we make sense of the world that we live in? In particular, we turn to documentary that either exposes new information (as in Taxi to the Dark Side and black sites in Afghanistan) or gives a new context to something known (as in The Act of Killing and the Indonesian mass killing). Or we can lean on the long history of fiction from The Red Badge of Courage to The Battle of Algiers to The Hurt Locker. Even when we cannot comprehend, sometimes simply observing and reflecting is all we can do.

Despite using war as a setting, games are absolutely allergic to talking about the meaning of war, especially in The Present Moment, with the clarity needed. They either have us enact violence to teach you a lesson (dropping white phosphorus on civilians in Spec Ops: The Line) or place you as a civilian (managing scarcity in This War of Mine) to, well, also teach you a lesson. But Kwan took a different approach–stripping down the mechanics to simply the act of observation, which, frankly, is more than enough. He doesn't need to tell you that war is an unnecessary evil; players already bring that to the table. "I want to create this space for people to put in their own imaginations and relate to what they are experiencing in the real world," he said.

Kwan grew up in Hong Kong and found himself pulled between parental identities. His mother, a banker, "is a logical person," he said, while his father teaches high school and loves art and film. He spent 23 years in Hong Kong, later focusing on interactive art, before moving to Boston for grad school at MIT. After bouncing around Boston, New Orleans, and Hong Kong, he landed a job at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago.

Games didn't initially appeal to him. ("Too competitive," he said. "It stressed me out.”) But frequenting the many dazzling arcades nestled among the tangles of Hong Kong's suburbs, he had a moment that shifted his perspective. There was one moment in particular that changed the way he thought about games. A young couple was playing a racing game, a normally competitive affair.

But instead of going head-to-head, the two teens had pulled over quietly to the side of the track. "They were just hanging out, seeing this virtual sunset in Tokyo," he remembered. The NPCs were whipping past them as their rank dropped and dropped, but they didn't care. It was an experience they wanted to savor together. It was in that moment that he realized that games "can be romantic; poetic, even," he reminisced.

Scent didn't begin as a project about war; instead, he began to reflect on what it would mean to lose his independence. In 2018, Kwan learned that his father was losing his eyesight and his field of vision would shrink over time. "I was envisioning a sci-fi game that you play as a robotic dog, and then the parts in the robot start failing," he said. But as the "global situation" began to deteriorate with conflicts in Ukraine, the Middle East, Myanmar, Afghanistan, and elsewhere, the game's long development cycle led Kwan in a new direction. He wanted to harness that ineffable, sublime feeling he witnessed with that Hong Kong couple in the service of creating what he was observing in conflict. "The game slowly became seeing human brutality and violence from the perspective of an animal," he said. If it wouldn't be about a specific narrative, "then it becomes like a sensory, physical experience."

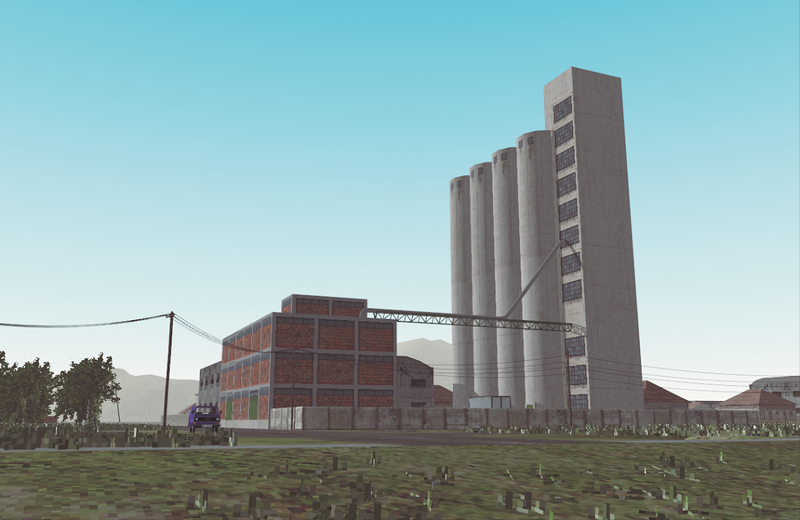

In most games, agency is power, but Scent pulls you on a rail that shifts through different biomes. You move from a forest to a field to structures, while bullets whizz overhead and screams can be heard off-camera. Bodies are slouched against walls, and you pass humans on their knees, awaiting an unknown fate.

But it's the deliberate ambiguity that is the most arresting. The characters are mostly faceless. No identifiable language is spoken. No national colors on which to pin blame or assign sympathy. The world is awash in a haze of bloom lighting. Is it dusk or is it dawn? Where are the sounds coming from? "In chaotic situations, I feel like most of the time you don't have like a clear visual sense of what is happening in front of you," he said of the sound design. I think that would create a more intense psychological experience than showing a lot of people die in front of you."

Typically, I find the single-track approach too facile, as it strips players of the tactile moments that can be so meaningful during play. But Kwan's decision, which both limits your movement while also backgrounding the violence, is an arresting choice, reminiscent of films like Zone of Interest, where what you hear is worse than what you see. "There are two films," director Jonathan Glazer told The Guardian about his Oscar-winning film about the Holocaust. "The one you see, and the one you hear, and the second is just as important as the first, arguably more so. We already know the imagery of the camps from actual archive footage. There is no need to attempt to recreate it, but I felt that if we could hear it, we could somehow see it in our heads."

Kwan also wanted to expand the context of violence as a feature of life on Earth, not just the sad dominion of humans. The game opens and closes with a hulking elephant that bookends the experience, and at one point, you are mobbed by crows who pluck the hapless souls you've collected for their own nefarious purposes. "The dog is kind of like a companion to all this suffering," Kwan said. "Nature is still brutal and violent as well." Scent provides no answers, only observation.