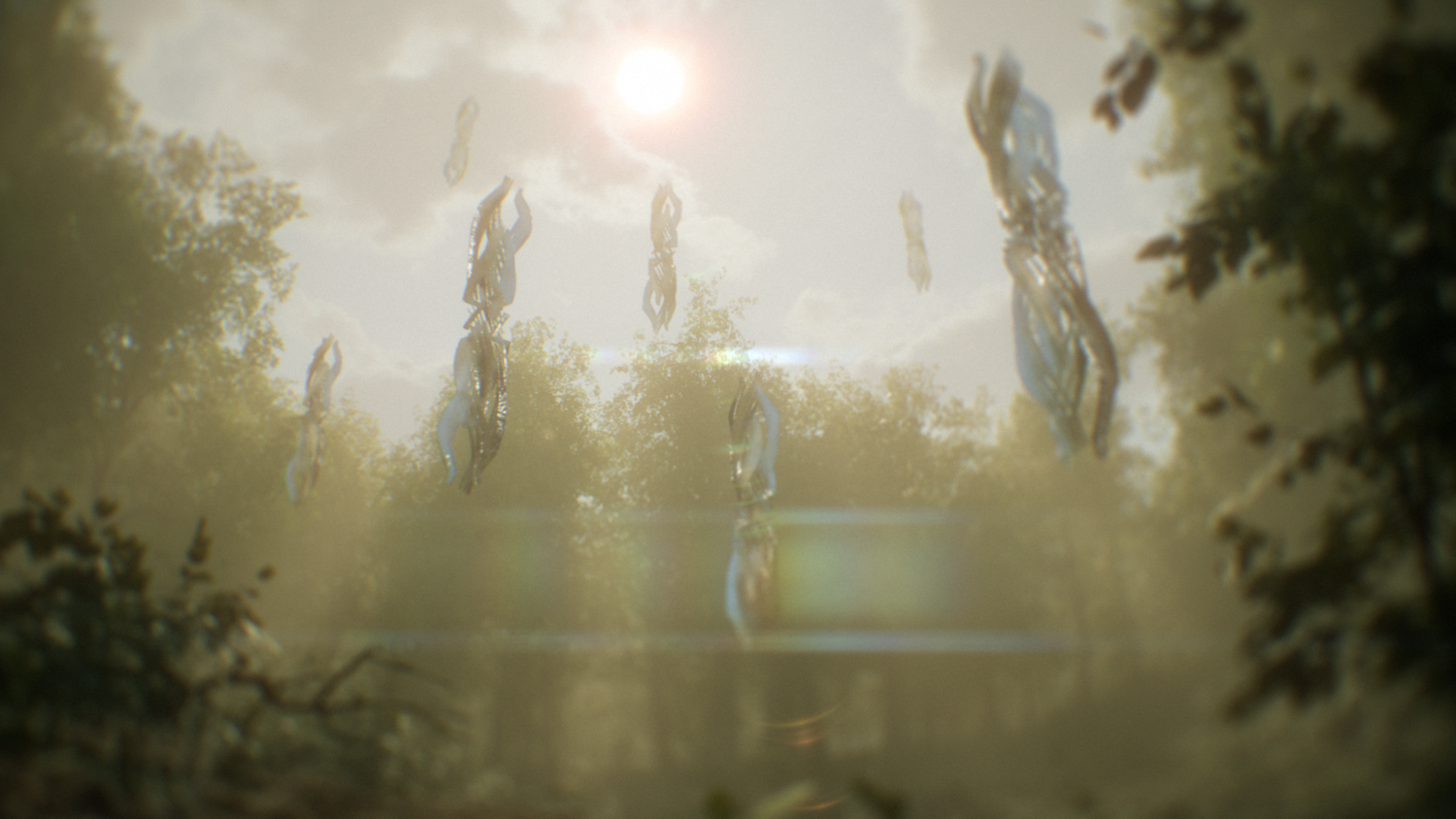

On a large stage at the Flux Festival in Los Angeles, Kevin Peter He grasps what appears to be a massive controller, the type you’d use for Flight Simulator, and stands tall against a large projected image of the body in free fall. Ashen and out of control, the body is pierced by light, and as He leans in and out, the figure is manipulated into a forest. The forest spins, shocks of flashbangs paint the foliage, and the character moves into the syncopated rhythm of flexes, bends, and flailings.

This is more than what you might find with “VJ.” He isn't pressing play on a pre-rendered video, and even more than something being controlled in real-time. He's on-stage as a performer—navigating, documenting, and interacting with this world in real time, his embodied presence as central to the work as the mesmerizing imagery on screen.

"I'm collapsing that filmmaking process into the onstage moment," He explains. "I am immersing myself at the same time as the audience." In filmmaking, magic happens on set, but that beauty is disintermediated, moving from set to editing, distribution, and finally to the screen. But on-stage, the connection between the play of a digital body, He’s digital performance, and my experience, as a spectator, is collapsed entirely.

Passage exists as both a live performance and an installation.

This intersection—where game engines meet live performance, where digital environments meet physical bodies—has become the distinctive territory of his work. He is part of a group of filmmakers and artists, such as Ina Chen and Theo Triantafyllidis, who are transforming the movement of human bodies into something we can watch and ultimately dance alongside.

Born in New York but raised primarily in Shanghai during its explosive urbanization, He returned to the United States with a unique perspective on how natural and built environments merge, diverge, and transform. His work addresses what happens when this relationship extends into the digital realm.

This tension led to an unconventional path—from underground hip-hop dance troupes in Los Angeles to studying film and data science at the University of Southern California (USC), financial modeling at Apple, and fashion design to immersive media. His eventual embrace of game engines wasn't to create traditional games, but to bridge his multidisciplinary background in an unexpected way.

Performing the Game Engine

In an era when game engines have become ubiquitous tools for everything from blockbuster films to architectural visualization, He focuses on something entirely different: treating the game engine as an instrument for live performance.

For 2023’s Passage_Chroniko, He uses a custom camera controller mounted on a mechanical arm with a programmable LED in the lens center. "I wanted to point to the process," He explains. The deliberate design choice makes his interaction with the digital environment legible to audiences—something often missing in game-based performances.

What’s fascinating is that games have a long lineage of flirting with performance, albeit in a less deliberate way. Arcades, by definition, invite an intersection of players' bodies. One pushed through the masses to place a quarter to claim your spot to complete. Dance Dance Revolution experts added additional movements, such as leaning on the backbar or incorporating movements that extended beyond pure score acquisition. Rock Band and Guitar Hero transformed what was essentially tapping rhythms on a keyboard into a full-throated performance, either by inviting disinhibition for solo players or summoning the spirit of the karaoke diva at a party.

Oddly, the most explicit performance of games in the last 15 years—esports—is devoid of the on-stage markers that would signal high achievement or expertise. The crowds are raucous, but competing esports athletes are nearly comatose, a thermodynamic technique to expend energy only in the service of mouse and keyboard. That bodily disconnect essentially robs high-level esports performances of visual legibility. An esports player performing a complex maneuver like "wave dashing" in Super Smash Bros. might execute something technically impressive, but the physical performance remains opaque in real life.

Compared with live sports or other game performances, my experiences at live events left me wanting more from athletes. The other week, I was delighted to watch Barcelona winger Lamine Yamal dance through a crowd of thronging defenders. Even a novice soccer fan can see brilliance in that type of physical performance. Writing about Julius Erving’s legendary baseline move, art critic Dave Hickey wrote, “Rules [...] translate the pain of violent conflict into the pleasures of disputation—into the excitements of politics, the delights of rhetorical art, and competitive sport.”

Even though the medium is game-based, He takes more notes from his experience as a dancer and works with electronic musician Jake Oleason. "There's a skill," He notes, "I think about it from an instrument standpoint, like for a musician. How do you make something that helps you do what you do, but then helps other people understand what you're doing?"

For his major performance piece, Flux—a work exploring turbulence and acceptance through the story of an android discovering humanity through dance—He takes a different approach. Using that flight controller with five-way hat switches, he essentially has twenty buttons under one hand, allowing for rapid, expressive control over cameras, lighting, and architectural elements.

"With Flux because there's so much going on, and the music is so kinetic," He notes. The performance becomes more like a duet between him and a motion-captured android, reflecting the balance between control and surrender.

Performance acts as a transformative force in gameplay by changing social rules rather than game rules. It’s still a game world I’m watching, but the context of a concert changes how I understand what’s on screen. This interplay between the physical and the on-screen is known as “intermediality” and is a specific lineage of performance that He is tapping into. Intermedial performances exist between the performance and the modes of production, serving as both an intervention and an assembly. As an audience, we both see the real-time construction of something new, but the centering of He on stage means that we are always aware that someone is in control.

From Shanghai to Real-Time Performance

What makes his approach particularly compelling is his focus on bridging the gap between performer and audience experience. Unlike traditional media where production and reception are separated by time and process, He's real-time performances create a shared moment of discovery.

"I think constantly what I'm trying to evoke with my work is that I am immersing myself at the same time as the audience," He explains. This collapse of traditional production workflows fundamentally changes the relationship between creator and viewer.

His background in underground hip-hop dance informs this approach, understanding how movement and physical presence communicate to an audience in ways that transcend technical execution. When he performs Passage_Chroniko, the slow, deliberate pushing of his custom controller through a 60-minute one-take journey invites viewers to inhabit the forest alongside him.

What happens when the relationship between performer and digital output is deliberately disrupted? This exploration centers what researcher Marleena Huukha calls “nonhuman agency” within live performance systems. Agency is created in the intra-actions between different actors on stage—He, the video game engine, the controller, and all of the other software that brings the performance to life. The ‘being’ on-stage and the “doing” on-stage are collapsed into a single moment when we experience what we’re seeing as an audience, as researcher Jo Scott would describe it.

He worked as an Unreal Engine developer on Lisa Jamhoury's Maquette, a live interactive exploration of the parallel histories of averaging and idealism in art and society. There's an interplay between the performers’ movements and the projected avatars behind them.

This perspective reframes He's performances as collaborations with nonhuman systems rather than just demonstrations of technical prowess. Scott characterizes the intermedial performer as a "creative technician," highlighting how these performances involve working between the actual and virtual worlds. In He's case, this involves developing a relationship with his custom controllers and game environments where agency is distributed between human and machine.

In his upcoming work for NEW INC, He is explicitly exploring what happens when "the tools start controlling us." As he explains, the question becomes: "How do we then have moments where it disconnects from that and transfers the function into the human body, and your attention shifts to the performer on stage?" This intentional shifting of control creates a dynamic tension where agency flows between performer and system.

He envisions "the gesture of performing a game or real-time visual component" becoming "a choreographic gesture"—transforming technological interaction into artistic expression. This approach acknowledges that video games fundamentally require nonhuman input to exist, making the relationship with technology not just instrumental but essential to the performance itself.

By deliberately complicating the connections between human action and digital output, He's work invites us to reconsider traditional notions of performance agency. The machine becomes not merely a tool but a participant with its own form of agency—sometimes leading, sometimes following, but always present in the creative dialogue that unfolds on stage.

Cybernetic Nature

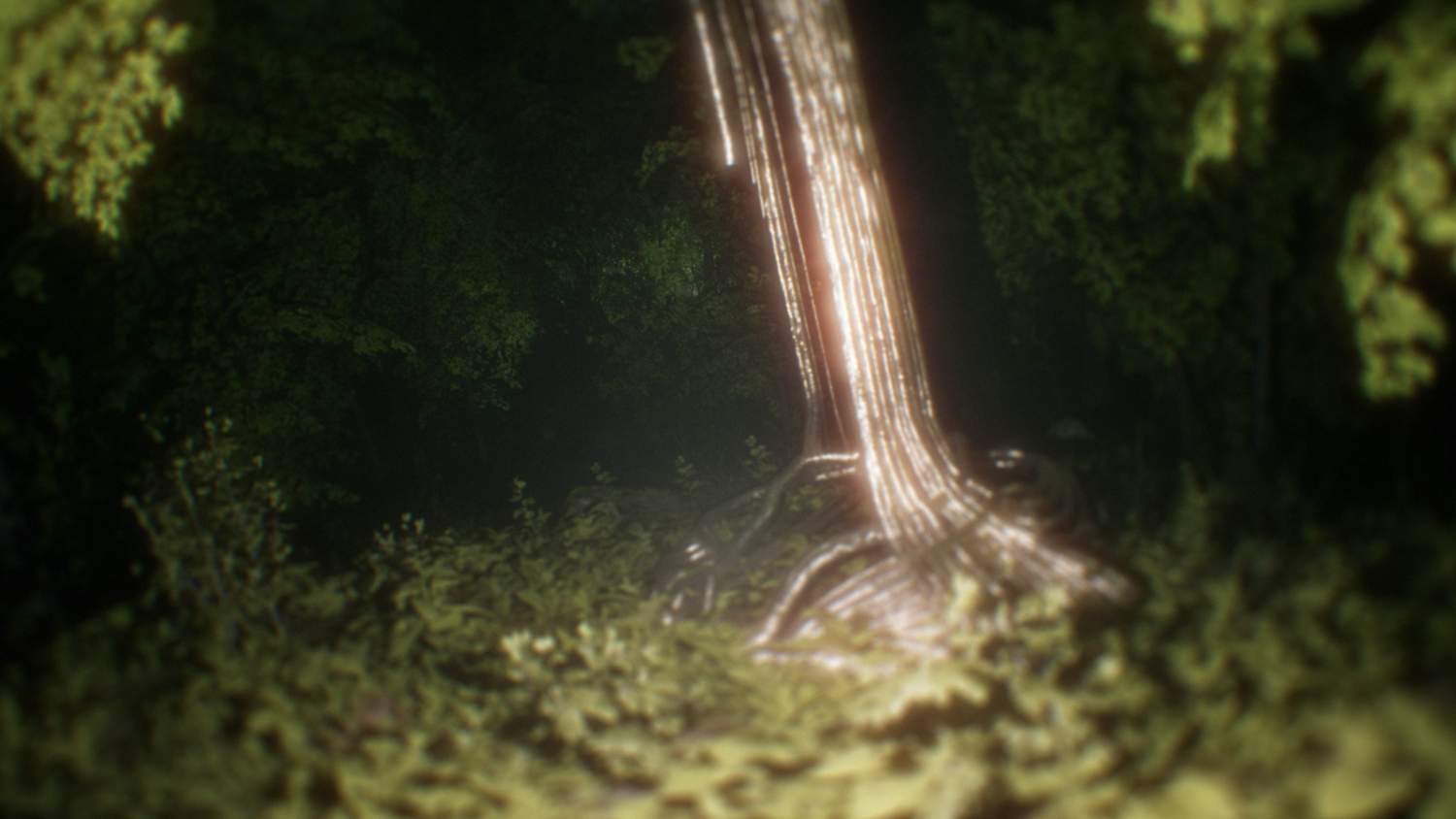

At the heart of much of He's work, particularly the Passage series, is a meditation on how nature is transformed through human and digital systems. Growing up in Shanghai, he observed how trees were specifically selected for their ability to survive in polluted urban environments. "There are specific city blocks with each tree called London Plane trees," He explains. Their specific characteristic is that they shed their bark. They can survive under harsh conditions and essentially combat industrialization or pollution."

Cool demo. Where'd everybody go?

This observation extends into his critique of how digital environments typically represent nature as technical showcases rather than living systems. "As we've all seen at NVIDIA's latest GPU conference, it's like, 'Okay, here's a photorealistic forest rendered in detail.' It's where there's no life in there," He gripes. Passage imagines what nature might become if born from computational systems, not attempting to mimic biological life, but finding its own way to persist within technological constraints. "The device between human systems and natural ecosystems just began to really collapse in that way," He reflects.

Ashee continues to evolve his practice, he’s exploring how the game engine might eventually disappear from the final presentation while still informing the conceptual framework. His upcoming installation for NEW INC 2025 combines a physical sculpture featuring a living Ficus benjamina with a real-time simulation, exploring how nature persists when forced to exist within artificial systems.

"I'm trying to use game engines as the core to tie those things together," He explains. "It's there to inform the whole world-building, but then it sometimes doesn't need to be fully there for the actual piece itself."

This evolution reflects a maturation in how artists approach game engines. There’s no doubt that game engine use will become the norm, so moving beyond technical novelty toward conceptual depth is important. What does a game engine add to the experience? Artists have to extend beyond the simple assertion that "this was made in a game engine” which will be as important as saying a film was shot with Panavision.

For He, the game engine provides a framework for system-based thinking and action-based expression, even when it may not be visible in the final work. "Even if the game engine itself disappears, those things stay," he observes.

The Future of Performed Environments

As audiences continue to expect more from live experiences, artists like Kevin Peter He are defining new territories for performance that bridge virtual and physical realms. By foregrounding his physical presence in relation to digital environments, He creates work that is simultaneously technical and deeply human—so human, that is uses the human body as its centerpiece.

His practice suggests exciting possibilities for engaging with digital worlds beyond traditional interfaces, incorporating dance, cinema, and sculpture elements to create experiences that feel more connected to our embodied reality.

"I want people to care for the environment, the world," He says about Passage. In a time when our relationship with natural and digital environments feels increasingly mediated and complex, He's work offers a compelling model for how we might find new ways to inhabit these spaces—not as passive consumers, but as active, embodied participants.

All quotations from Kevin Peter He are from a personal interview conducted in April 2025.