My grandfather turned 94 this year, which is wonderful, but also strange. If you have parents or grandparents this age, there’s always a tinge of sadness every time you visit, even if they are in great shape. I wrestle with saying “good-bye” or “see you later,” knowing that this might be the last time I see him, but wishing for many more happy returns. And much to my grandfather’s annoyance, I’m desperate to squeeze every last memory from him—more details about my grandmother, who died before I was born, his bike route as a young kid in 1930s San Antonio, his time as a young Mexican-American in the Korean War, and so on.

Like me, artist Ina Chen shared those same competing desires for connection with her grandparents, who lived on a Chinese nuclear research facility. “I interviewed my grandparents and listened to how they navigate their life with a huge consideration for the next generation,” she told me. “I found it's very universal.”

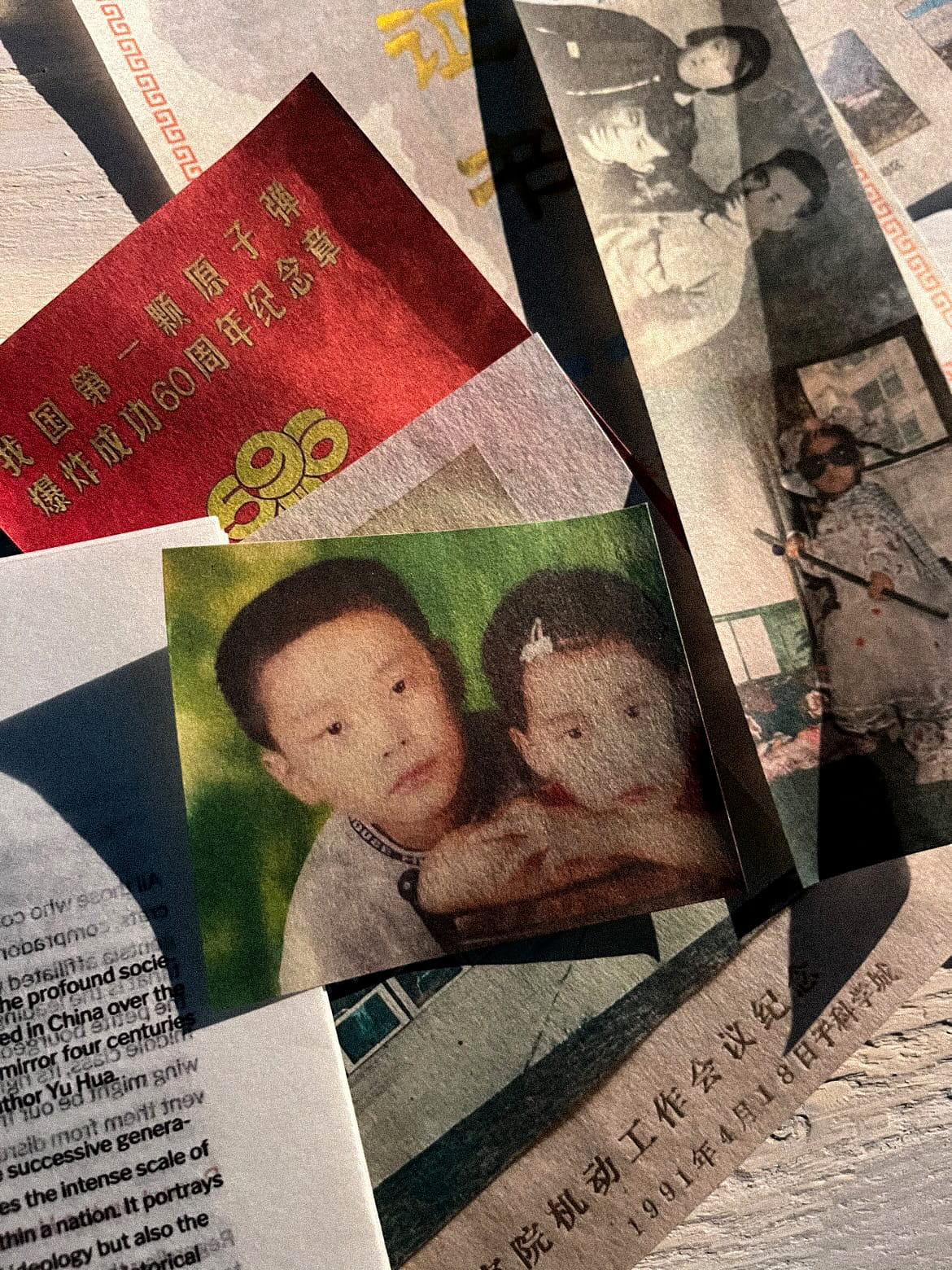

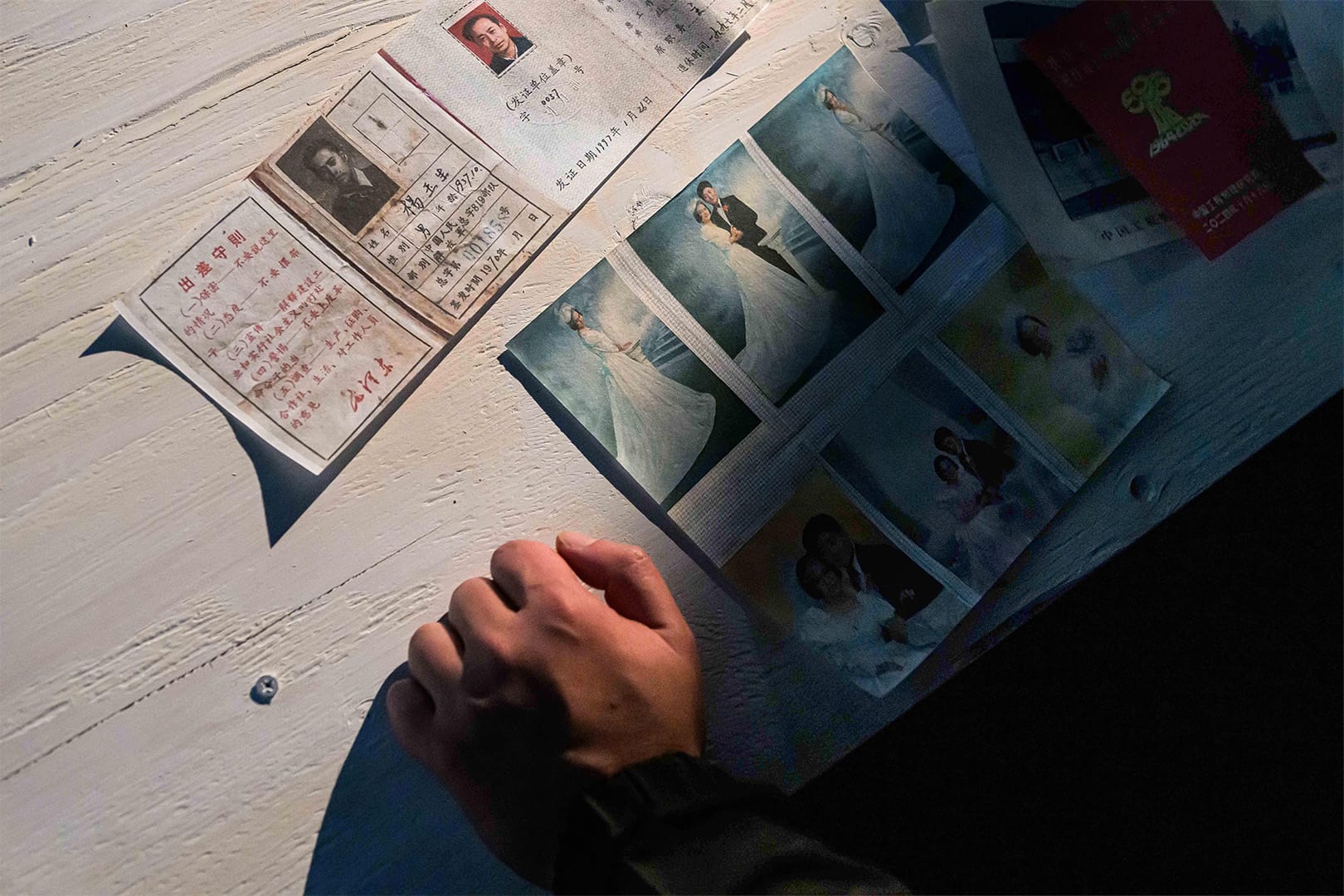

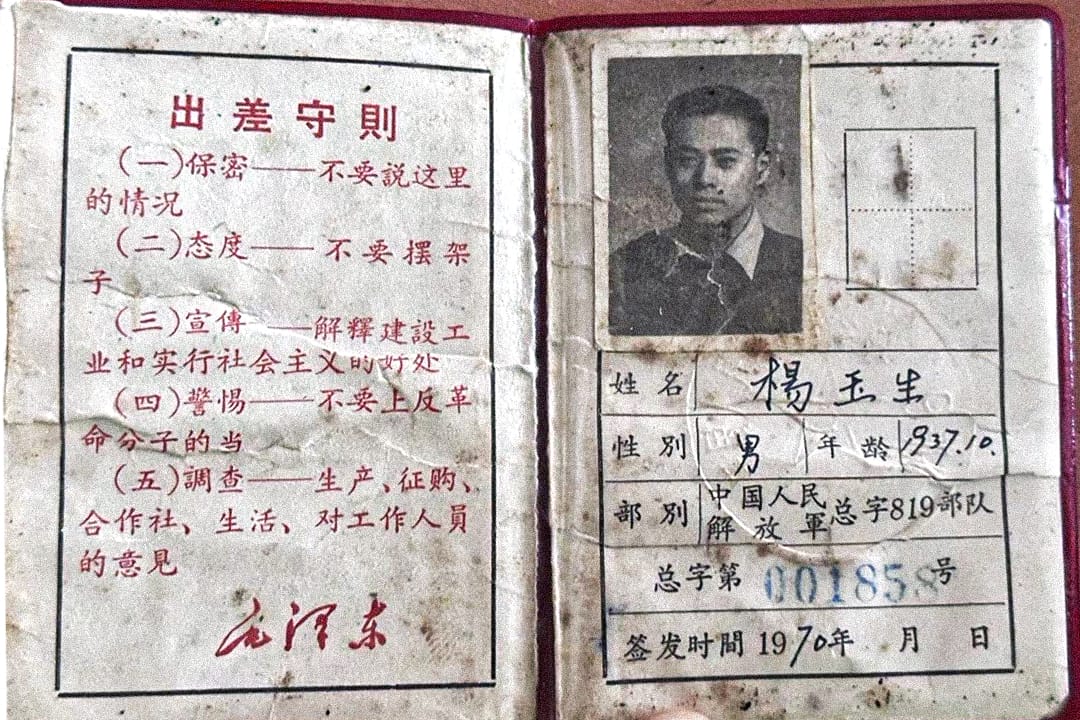

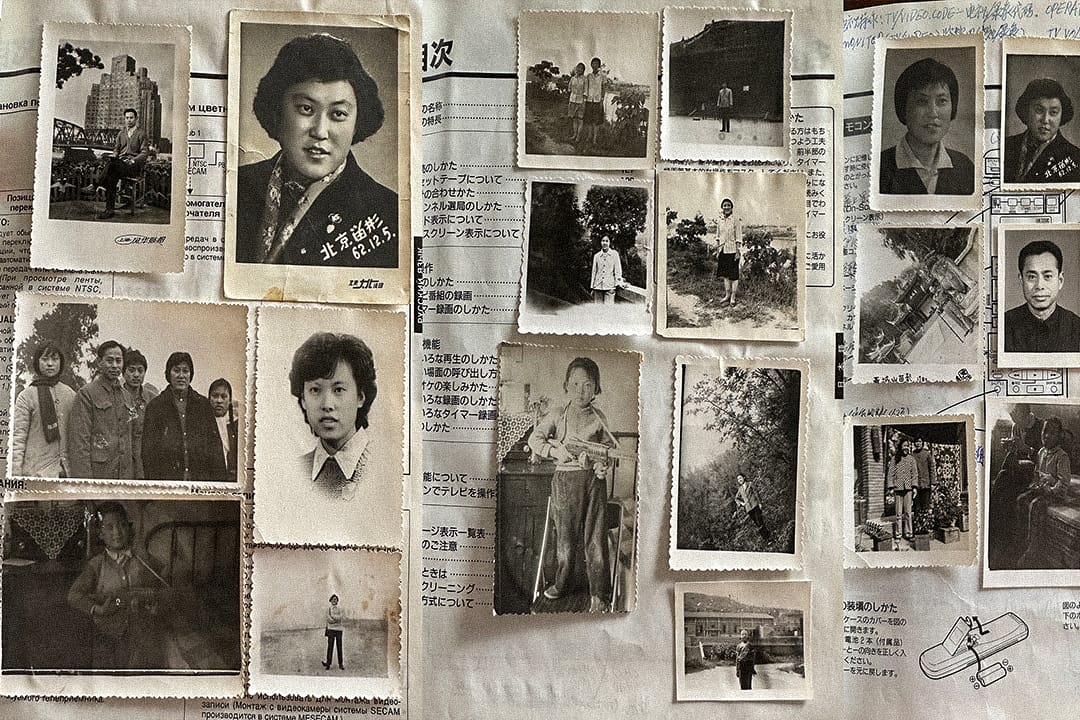

Chen’s interviews with her grandfather and mother became a new multi-layered work called “Generation of Books” that charts her family’s journey through over a century of Chinese history. It is a reading, a performance leveraging photogrammetry and deep-fakes, and a physical installation of meaningful objects from her family. She created an 8x8-foot wooden platform inspired by the traditional Chinese kang (an elevated, heated seating area) for audiences to move around the archival materials—ID cards, wedding photos, food coupons, exam papers—before settling in for the 25-minute performance. "

With Generation of Books, Chen has created a dialogue across generations to find the common ground and cultural divides that have shaped her, her mother, and her grandparents. “You can still sit at the same dinner table, talk, and share your life while the differences are huge,” she said. "What does it mean to take a family archive to talk about these generational conversations?" Chen said.

The backdrop, of course, is one of rapid change that’s hard to explain if you’re not Chinese. In contrast to European or American history, which spread its economic rise (and fall) over centuries, China's economic development from an agrarian to an industrial society is a story told in mere decades. After multiple failed attempts to industrialize through the 20th century, China quadrupled its share of global GDP over the last forty years, carrying hundreds of millions of people into a more prosperous but sudden future. “China has been developing so fast,” Ina said. “That's why the gap between each generation is so large.”

Objects from Chen's documentary work

Three Books, Three Worlds

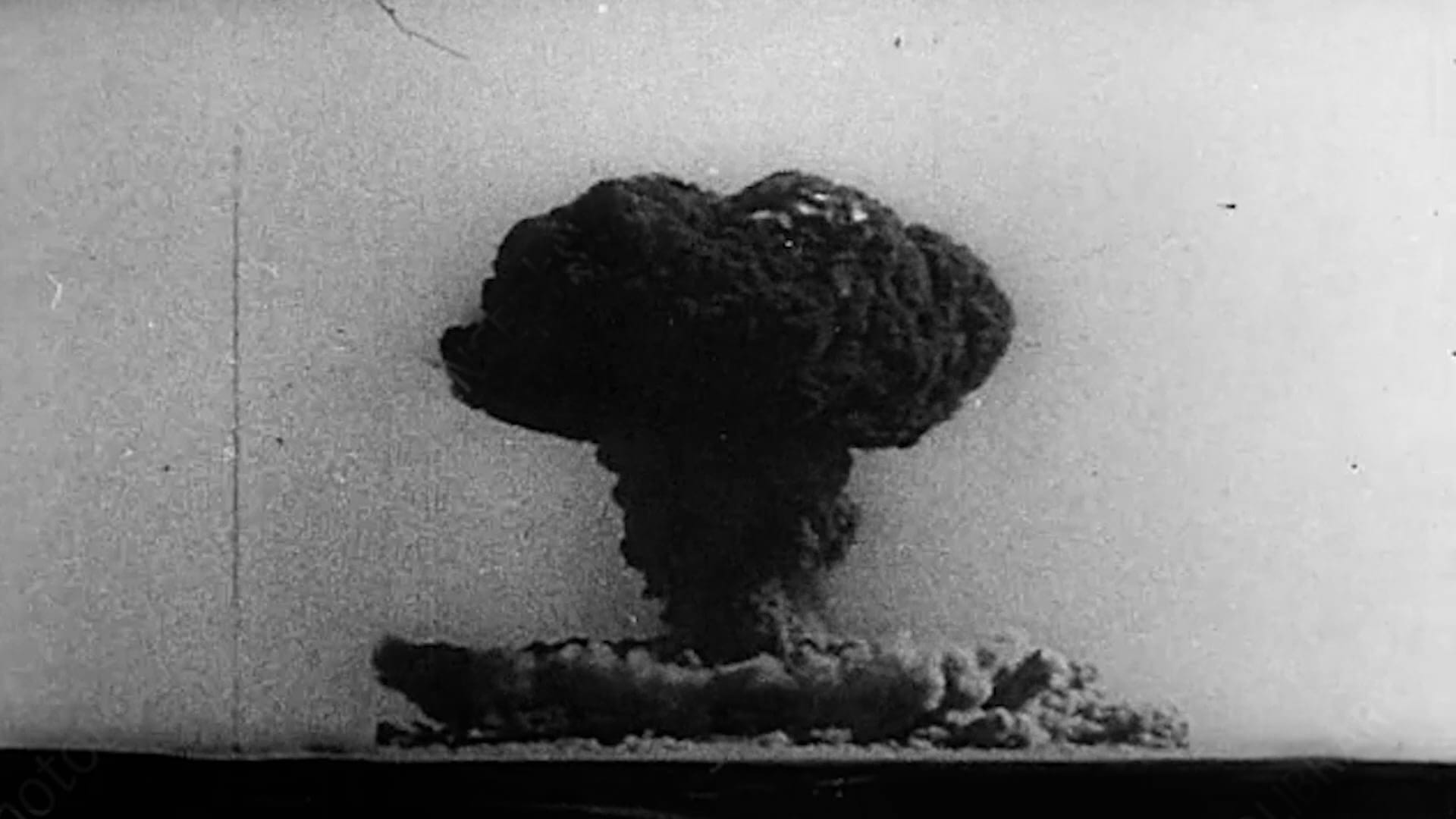

For Chen, the story of China’s evolution is told through the stories of her family, and more specifically, through the objects she remembers. She remembers her 91-year-old grandfather climbing a ladder to retrieve a single photograph from a high shelf, a tremendous physical effort to bridge a generational gap with the power of recovery. For Books, she highlighted three pieces of writing to serve as an individual signpost for a family member and a metaphor for that family member’s distinct place in their family and national history. Her grandfather chose “Selected Works of Mao” from 1960, which connected his work at the China Academy of Engineering Physics to develop the country’s first atomic and hydrogen bomb, to the needs of his country and family. For Chen's mother, a copy of Reader’s Digest highlights her mom's dreams of stability and joy with family, children, and property.

Chen's life and attendant questions have developed differently. She migrated to the United States and Europe in 2012 and has pursued a career as a director, artist, and designer with a strong focus on architecture and experience design. Her selected book for the work was “One Hundred Thousand Whys," an encyclopedia that spans all disciplines, but also contrasts the openness of her future life states with the limited ones of previous generations of her family. "My generation is one of curiosity, I think," she says. "But at the same time, it's confusing for many people in my generation, balancing family, life, and work. Well, my grandparents, even though there's very little freedom, everything is taken care of. It's a huge flip."

Technical Choreography

Chen is manically multi-disciplinary. I first encountered her work with “4993 Feet Under," an ambitious real-time performance based on the Deepwater Horizon disaster. Chen dubbed the performance "live cinema," as it pulled in game engine performance with music and visuals. For 4993 and other live game engine performance, the uncertainty is on the performer's side, where any technical glitch can tank the performance.

The intimacy of Books required a different type of risk for Chen. She decided to integrate several technical elements into the work's live performance. After viewers are invited to inspect the collection of objects, she presents them with a scrupulously designed 25-minute set that interchanges readings from the physical works with various dynamic elements to build out her family's story, all projected on the three walls surrounding the stage.

Each familial chapter in the performance featured its unique approach to future technologies. For her grandfather, Chen worked with 1950s archival footage of Chinese atomic bomb tests and matched them with 3D scans of work compounds. For her mother, she created AI-generated depth maps to manipulate sequences from Ron Fricke's globe-trotting conceptual film Baraka to capture the feeling of her mother's unexpected modernity. And for herself, Chen reconstructed the pieces of rocket debris from the failed 1962 Atlas Centaur rocket featured in the final scene of Koyaanisqatsi. Using live hand-tracking, she choreographed and controlled the collapse of the rocket, a bookend to juxtapose the certainty of her grandfather's life with the open-endedness of her own.

For the readings themselves, she chose an unusual vessel for earnest communication: deepfakes. As Chen read from each of the books, her face and the faces of her mother or grandfather would slowly drift across the screen, leaving a faint trace, before overtaking Chen's. For a moment, all three generations acted in unison and merged their separate histories into a collective one. In particular, she wanted to avoid the uncanny effect that deepfakes often carry and made the faces indistinct to maximize the feeling of her words over deception. "Generational identity flows onto you as a conceptual mechanism," she said.

Memory as Labor

During one trip last year, Chen began creating a unwitting memorial. Her grandmother had been unable to talk, but communicated with her grandmother through gestures during Chen's interviews. Her grandmother passed away a few months later.

The loss of a grandparent is hard, but the unexpected intimacy of the documentation was sudden and weighty. "The making of this performance was a way of remembering her but also her generation," she said. "This generational piece is also so momentary. It's not something permanent that's represented in this work." What began as an act of documentation became a significant intergenerational exchange, transforming archival preservation into a final, shared moment of remembrance. What was once three generations will soon become just two.

Someone once told me that history is just three train cars, and every thirty years, the last vehicle detaches and leaves everything behind before a new one emerges at the front. The work of memory, then, becomes shuffling essential items from one train car to the next. But for those tasked with thinking about the future, what we take with us is both a burden and a joy. In those little moments–the brief phone calls in the car, the hurried scans of a 60-year-old photo, the brief aside about your grandmother's smile–we lay down the track.