How Gaming Taught Culture to Randomize Desire

I don't need to tell you about the wild success of Labubus. The fuzzy, grotesque baubles have become a runaway commercial hit this year with chronic shortages, the latest in a long string of toy successes that blur the line between adults and adolescents.

Of course, with success inevitably arrives critique and the condemnations range from rampant consumerism to their playful ugly aesthetic. In a recent New Yorker article on the rise of Labubu's, writer Kyle Chayka desperately tried to make sense of the visual noise that emanates from these creatures: "We are the Labubus, grinning ecstatically amid the wreckage of our rapidly dismantling, recombinatory era." Grim!

But as someone invested in games, one element demanded a closer look: blind boxes. In a break from traditional retail, blind boxes are sealed and designed packages so you do not know what specific item is inside. One does not simply purchase a Labubu–you purchase a chance to own a particular Labubu. There's simply no way to complete your set predictably. You can only keep buying. It's a lottery ticket.

Randomized distribution is not a new phenomenon in retail. In the mid-19th century, cigarette cards were inserted into tobacco products, and later, random sports cards of baseball players entered the public market in the early 20th century. Collectible card games like Magic: The Gathering and Pokémon TCG brought randomized booster packs and introduced layers of rarity with a tier system. In Japan, throughout the 80s, popular gashapon (capsule toy vending machines) came with a random toy in a little plastic bubble. These toys later became designer objects throughout the 90s, merging with a streetwear emphasis on hyper-rarity. In the internet age, retailers like Pop Mart, Funko, and Loot Crate delivered the surprise mechanics with profound effect before leveraging streaming platforms to make the big reveal an online spectator event.

The problem is much larger and more apparent as Labubus are just the tip of the iceberg. Gaming's connection to gambling highlights how our broader culture sees more and more gambling elements working into all parts of our daily lives. Now, brands like Temu and Starbucks use spin to win features, quizzes, and elaborate referral systems on their sites. Cryptocurrency sites pull a page from FanDuel and offer free cash for signups. And just this month, the owner of the New York Stock Exchange took a $2 billion stake political in prediction market startup Polymarket, which seeks to expose financial markets to betting on sports, entertainment, and politics events.

But beneath the surface, a broader trend in gaming has helped lay the groundwork for our contemporary fixation. The point with Labubus is the aesthetic, but the mechanic also matters. How they are attained is meaningful because we're seeing the physical manifestation of a digital habit. As more IRL interactions have an explicitly digital component, games have offered a blueprint for where our economic lives might go. When I asked Joseph Macey, a post-doctoral researcher at University of Turku who focuses on gaming and gambling, about Labubus, "It's not exactly gambling," he says. "But these kinds of behaviors are used to encourage ongoing consumption."

But he had a simpler word for it: "gamblification."

But Is It Really Gambling?

Macey was almost fated to be interested in gambling. His grandfather used to organize a national sweepstake for the annual steeplechase race winner, the Grand National in Liverpool. Later, family games of gin rummy became an annual point-tallying tradition that would net the winner an extra present at Christmas. When his research led him to esports, the ties to gambling were immediately apparent, and he focused his thesis on the convergence of games and gambling. After advising Topias Mattinen, now a doctoral researcher at Tampere, on his master's thesis, the two began working with Juho Hamari, professor of gamification at Tampere, to dig more into the gaming industry's increasing reliance on gambling.

Before we start throwing around the big G-word, getting clear on terms is helpful. First, there needs to be something at stake. It could be money or objects, but it needs to have some material value. Second, the outcome needs to be uncertain. In roulette, no one knows where the ball will stop (although many have attempted to try!) Finally, there must be a prize. It could be financial or another type of game. Put together, gambling is "Staking money or something of material value on an event having an uncertain outcome in the hope of winning additional money and/or an item of material value," according to Macey and fellow researcher Juho Hamari.

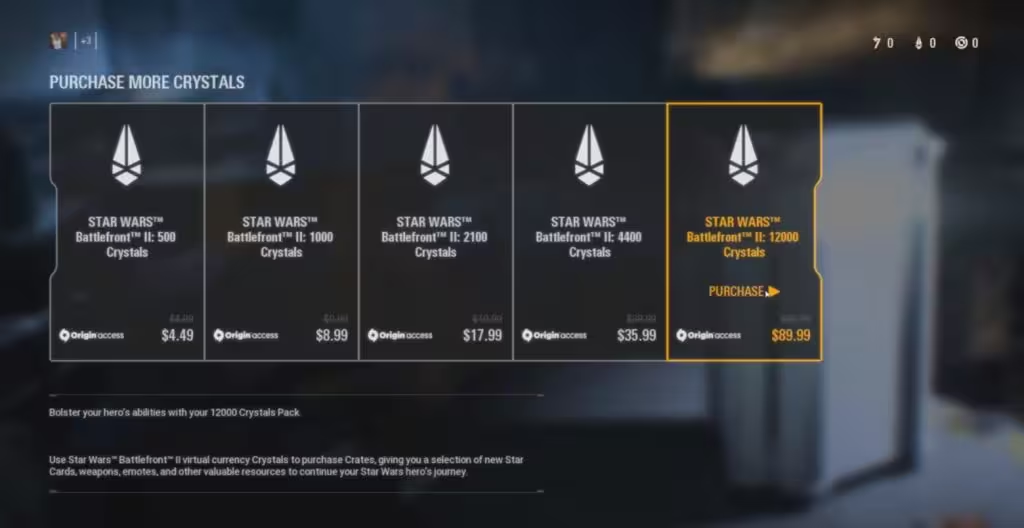

Gambling games and video games share a common ancestry; introducing gambling-like elements into games is a relatively new phenomenon in this century. Asian gacha mechanics (named after the previously mentioned vending machines) crossed into Western markets through mobile games, before making an ominous appearance in 2017 when Star Wars Battlefront II added loot boxes and randomized reward containers requiring payment to open.

Even as someone who plays games quite a bit, I was surprised by the breadth of gambification techniques in games. Aside from loot boxes, there are weapon cases that drop for free, but you need to purchase a key to open them. FIFA's Ultimate Team pulls directly from trading cards with randomized players. There are battle passes with time-limited rewards, daily bonuses that encourage you to come daily, in-game betting systems, virtual currencies that hide real-money conversion, secondary markets to bet on and trade digital goods, and tournament-specific rewards. All this is on top of actual betting on the outcomes of games.

Instead of experimenting with new play styles and finding new players, game companies are attempting to colonize more and more of existing players' time, attention, and resources. It's then inevitable that the "innovations" are around extracting every last drop, even if it means getting danger-close to the casino.

Real Gambling vs. Near Gambling

The challenge is that gamblification in games deliberately blurs the boundary between the casino and play space. "You have these gambling mechanics where you might not spend money; you get stuff for free just by logging in," Mattinen says. But if you're not spending your money, is that gambling?"

But what do players think? In their research for their paper "Play, Pay, Profit," Mattinen, Macey, and Hamari spoke with thirteen players worldwide to get a better sense of how they think about that line between gambling and gaming. The work revealed a complex and nuanced literacy across a range of activities.

The big revelation for the researchers was the concept of "cashing out"– players saw the fuzzy line between gambling and gaming, but only thought that gambling occurred when players transferred non-monetary winnings into real-world cash. Some activities were a clear bright line, like selling an account or in-game item on a third-party site, but others were cleverly disguised. Players have learned that they can convert Steam credit (earned from selling virtual items) into physical hardware like the Steam Deck, which then sell for real money. "Players are the ones who have the best grasp [of gambling in games]," Macey says. "They are not ignorant about what's going on."

The challenge is that our brain chemistry is wired to value uncertainty. The highest dopamine release isn't a win, but the moment just before the outcome is revealed. No matter how literate players might be, our bodies are not wired to resist, no matter what we think we know.

Gambling, Gambling Everywhere, But None for Me To Plink

Macey sees gamblification spreading into more areas of civic life in two key ways. First, the aesthetics of gambling are simply alluring and spreading. James Bond has always had an allure, and Las Vegas gambling revenue hit an all-time high in 2024 for the fourth year in a row. Ads for betting websites like FanDuel and Betfair are omnipresent across sports, normalizing and popularizing complicated arrangements like parlays. "Gambling is being shown as this way of having excitement and thrills in your life," Macey says.

But there's a more pernicious side for which video games are sadly leading the charge. Macey said that the simple functional use of gambling mechanics to add a bit of spice to any interaction is increasingly becoming the norm. Blind boxes are just the beginning, and even more pernicious uses of gamblification will surely make their way out of video games.

For example, Hearthstone uses a "pity timer" to prevent someone from being too unlucky when opening packs of cards in the game. If you hit a bad run, you will get an Epic card no matter what. This system is presented as a fairness system to protect players' time and patience, but it functions as a lure to ensure you keep coming back. Macey foresees other industries learning from techniques such as "time-gating," which deliberately slows players' progress and social comparisons that pit players against each other. How long until Pop Mart macabrely sends you Labubus part at a time? Or shows you which other Pop Mart customers have spent just a bit more than you on their leaderboard?

Whether it's Labubus, loot boxes, or Temu spins, "It's a very simple thing in the end," Mattinen says. "People like excitement and winning. That's what triggers us."