Artist Dom Rabrun sarcastically remembers the first game about the Haitian Revolution. "It's an Assassin's Creed offshoot made by mostly white folks," he says, his voice picking up speed, volume, and intensity as he teases out the story. "'Shh! Shh! Wa! Shh! Shh! I'm gonna free slaves! Oh my God. Psh!' You freed the slaves! Bah-bah-bah-bah-bah!,” he gesticulates from his apartment outside Washington, D.C., and describes a game that’s more like Call of Duty than 12 Years a Slave. He pauses. "That's what we're doing?" Rambrum snorts.

The Hyattsville, Maryland-based painter and game designer isn't interested in making that game. His project, Vèvè-Punk: Mind Singer, approaches his heritage and the Haitian Revolution through dialogue and choice rather than combat. The protagonist, Fabienne, is a free woman of color, a telepath and singer with zero strength and dexterity, who returns to the village to stop a super-soldier attempting to sabotage the Haitian Revolution. "Physical violence is so easy in games," Rabrun says. "I'm really interested in the conflicts that happen when a formerly enslaved person is talking to someone of a different social status and has to pretend like he doesn't know something.”

This “double consciousness” is precisely what has kept the diaspora alive throughout the former enslaved labor colonies, and capturing that tactical linguistic specificity is an interesting design challenge. “What does that dialogue tree look like for someone who's like, 'All right, if I don't say the right thing, this dude is gonna murder me.'"

Part of the new crop of visual artists who grew up on games and now are approaching the medium with their brush in hand, Rabrun's path to game development wasn't direct. He lived in a rent-controlled building in Brooklyn, raised by his mother, who bought him and his brother a Mac in 1994, when she was dying of HIV-related illnesses, and most Americans didn't own computers, especially BIPOC Americans. He remembers specific games with unusual clarity: Flying Colors, a proto-Photoshop program that let you create strange animated tableaux. Super Mario World on a neighbor's Super Nintendo, the sound still vivid decades later. “It’s been this dance of me being so in love with games as a medium and for portions of my life trying to downplay just how important they are to me.”

Aside from the cultural penalty the arts-minded can endure when taking games seriously, Rabrun’s religious community complicated his affection for it, while also enhancing its allure and adding a touch of the forbidden. Raised as a Jehovah's Witness, drawing comics—his first love—meant drawing violence, which wasn't allowed. Art itself wasn't exactly encouraged. "I come from a very conservative Christian, super working-class family," he says. "Drawing for me was always my thing, and I was rarely, if ever, praised for it or even barely acknowledged. It was like, 'Oh yeah, that's a thing you do.'"

He discovered comic artist James Jean around the same time he connected with Basquiat, and his practice has attempted to blend his two loves by drawing heavily on Haitian and Caribbean tradition. He spent two childhood summers with an aunt succumbing to the distraction with his nose pressed firmly in a GameBoy Color with Pokémon Yellow. The trip left impressions on him, if only that it was one of the few times his homeland was treated as a vibrant place, not an empty threat to send him away.

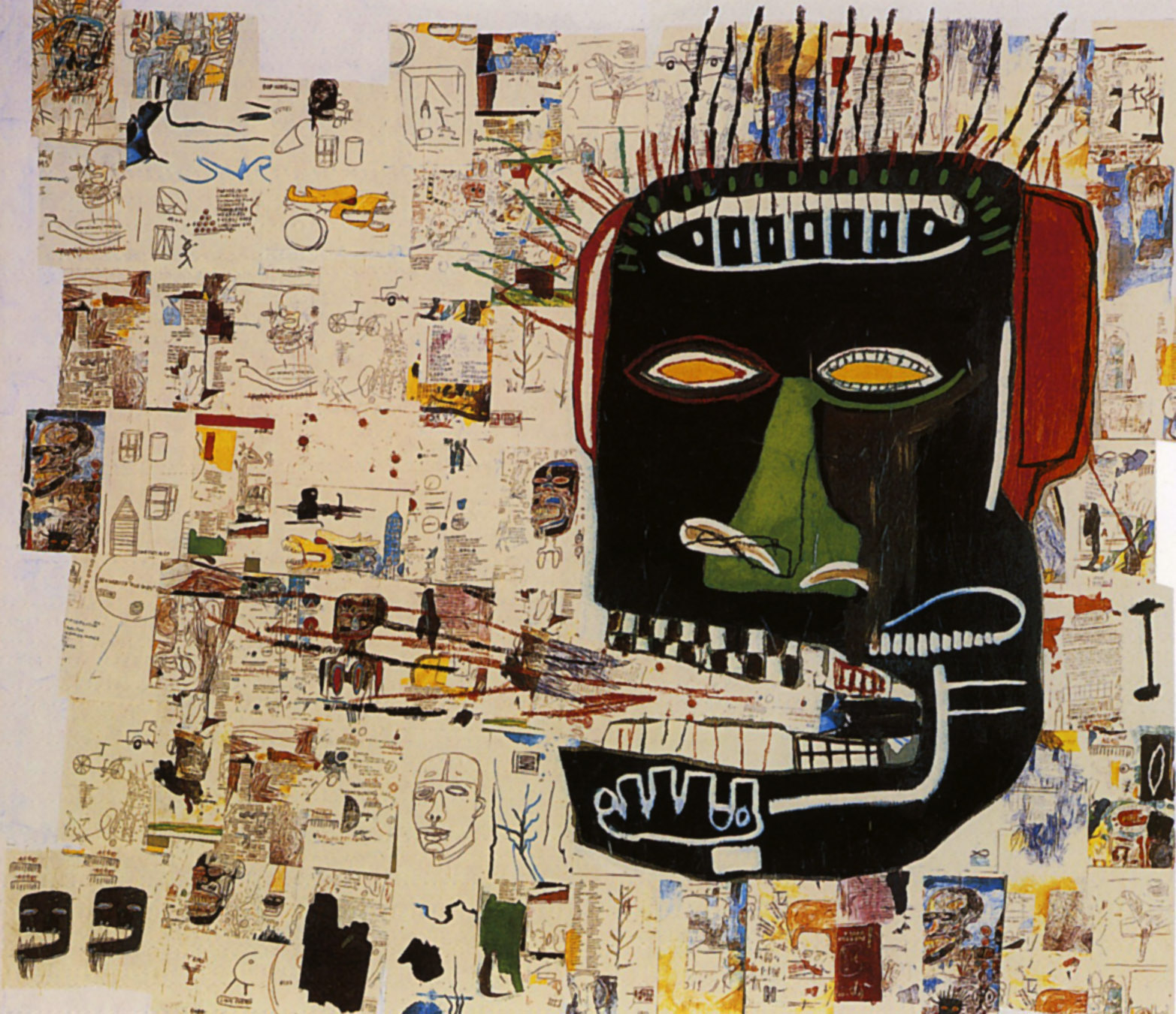

Basquiat was both an obvious entry point, a comparison that he bristles at as a lazy touchstone for any Haitian artist, but his encounter with Glenn (1985) at the Museum of Modern Art conceptually opened doors for his future game practice. In the seven-foot canvas, an enormous head speaks–no, screams—into a white background, an attempt to puncture invisibility with the power of sound. To Rabrun, the painting was an invitation to step into the work through the language of computers. “If you could imagine right-clicking on an element of a Basquiat painting, what does that menu look like? Pretty much any element you click is gonna give you sound, video, weird shit.”

In Rabrun’s paintings, flat perspectives force foreground and background to hold equal weight, where a goat and a hurricane share the same visual importance. "It's ancient wisdom," he says. "Our ancestors knew a thousand years ago that the earth is important. You should be able to hold a leaf and be like, 'The leaf is me too.'" That compositional approach, he notes, flies in the face of games' typical hierarchy of player over non-player: "I click this thing, and my character moves here. What does it mean to even hold this controller and control someone?"

His painting practice eventually led him back to games through Hip Hop RPG, a six-episode animated series about an SNES-style RPG starring Kendrick Lamar, Drake, and Tyler, the Creator in a post-apocalyptic world. The work is a bit of a time capsule, given how complicated his protagonists have become over the last few years (Kanye, let's say, hasn't aged well.). In the first episode, Drake heals Kendrick—a detail that feels stranger now,w given their current relationship. The series never finished. "I was a baby writer," Rabrun admits. "I hadn't scoped out the whole story."

But Hip Hop RPG taught him what he wanted to make. It also foregrounds Black art and establishes his voice as someone looking to translate what animated Rabrun about our culture. When Black Public Media executive producer Lisa Osborne saw his pitch for a character-select screen showing the racial and class stratifications of 1790 Saint-Domingue, she told him to turn it into a real game. "I was like, 'Oh my God,'" he recalls. "And she was right."

The challenge goes beyond game design. "Being Black sometimes, when you're just trying to make stuff that’s historically accurate, you feel like this...ugh," he says, searching for words. "Like you think of something like Amistad or Roots. And I ask myself this all the time: Does this work in games?” It’s a tension I feel personally–I want to foreground Black joy, but it can be hard to find that wonder when the past, present, and future can seem so burdened. “On the flip side, I'm like, okay, well, how many games have I played about a samurai? Or a fiefdom in ancient Europe somewhere. And I'm like, okay, well then why is this one uncomfortable?"

Mind Singer is now 70% complete in its vertical slice phase. The game is playable, though Rabrun knows it needs more narrative tension, more of what makes stories work. “What are Toussaint Louverture’s stats?” he wonders. He's aiming for something between Donald Glover and David Lynch, citing Disco Elysium as a touchstone. "I want games where you sit and think about stuff and talk," he says.

These quiet acts of resistance, rebellion, and occasional violence are more in line with contemporary understandings of enslaved rebellions. “Because slaveholders wrote the first draft of history,” historian Vincent Brown lamented in The New Yorker, “subsequent historiography has strained to escape from their point of view.” Brown argues that it’s better to think of each uprising as part of a larger struggle for freedom, rather than isolated acts of bravery, a sentiment Rabrun echoes: “I'm walking on ice. I know that. It's like you have to make these deliberate choices for how the audience will see it."

There's no lineage for what he's attempting. Unlike film, where decades of diasporic filmmakers from Oscar Micheaux to Charles Burnett to Ava DuVernay built a tradition, games offer a sparse foundation in need of deeper historical scholarship. There are wonderful new communities like Game Devs of Color, but the future history of Black game design is really starting today. "I got a little terrified just now," Rabrun says when this comes up. "It is kind of me in this place. I'm like, okay. And I have this awesome team, and we're like, okay, we're gonna do this thing."

In some ways, Ubisoft did him a favor. They took the low-hanging fruit—the combat, the stealth kills, the "freed the slaves" achievement notifications. Now Rabrun is free to make something else entirely.

"I'm not interested in showing the murder," he says. "I'm interested in what that dialogue tree looks like." Saint-Domingue had 16 racial classifications. Navigating that social structure without a weapon—only words, only choices, only the consequences of saying the wrong thing to the wrong person—that's the revolution Rabrun wants to put in your hands.