Trauma is about a woman who is in an accident and hospitalized. That’s about all I can say. Not because of spoilers. There are none. Nor is the plot some simple ruse to trick you into doing adventure-game handiwork. You don’t connect drainage gutters to solve a puzzle, or use a screwdriver to open a rusty circuit-breaker box. Trauma is about a psychological response to the irrational, rather than a pursuit of logical ends. At times, it conjures feelings of insomnia and anxiety. The biggest decision you’ll face may be whether to play after you’ve taken your prescription of Xanax—or Ambien.

Other than the Polaroid snapshots that are scattered throughout four ghostly places, the disjointed confessions of a therapy session are all there are to go on. It is uncertain, and perhaps unimportant, whether you are playing as the patient, or her psychiatrist; if you are wading through time-lapsed memories, or interpreting a recurring dream. Whatever the case, you find yourself in the head of an emotionally withdrawn woman, exploring a switchyard, where she chased a ghost as a child; or the cafe where she ate during law school. Each scene has a straightforward objective, like rescuing a teddy bear trapped underneath a rock. You click around, sleepwalking, finding childhood photos in odd places. Some are on the sides of heavy machinery, or lying on a cobblestone road. A few contain clues, used to solve simple puzzles.

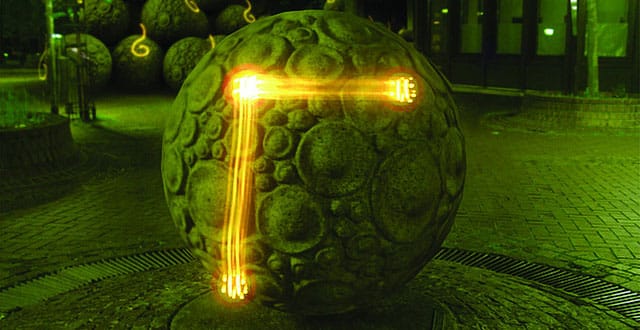

Krystian Majewski, the game’s creator, has said Trauma expresses the loneliness he felt as a child, inspired by “empty hospital hallways and anonymous railway stations in foreign countries.” He has captured those feelings in a series of eerie photographs he shot as the basis for the game. Faded like memories, these photos are mapped into dead city streets and haunted industrial yards. You click your way through them, as if Myst were charted in Google Street View, or as if you were using a family photo album to plot out Zork. The frames are photo-real, yet suggestive, colored by hazy streetlights, desaturated sunsets, and the psychic phenomena of spirit orbs.

The nondescript story, and the undemanding gameplay, run the risk of spinning in circles, but the result is in fact refreshing.

By every measure, Trauma is brief and imperfect. Finding your way around can be confusing. The story ends before the main character has been properly introduced; and the objectives, which amount to little more than a hidden-object game, are there if you feel like it. The nondescript story, and the undemanding gameplay, run the risk of spinning in circles, but the result is in fact refreshing. Ordinarily, adventure games speak in absolutes. 999 spelled out every cryptic detail, leaving little to the imagination. The Dream Machine read more like Stephen King than Kafka. But Trauma’s story merely suggests what to think. Truth is blurred.

The game is controlled through a series of painterly strokes. You paint a curly-Q to lift rocks, a half-circle to turn around. Much like the controls, the theme is painted with gestures. At one point, the camera pans out to reveal that the road is a Möbius strip circling the Earth. Also, the woman constantly makes mysterious comments. “It’s one of those dreams that never ends,” she distantly states. “It seems to continue even when I am awake.” The resulting emotions are ambiguous. Trauma lingers on the edge between solemn and chilling; profound and inconsequential; and there is an ever-present sense that you are lost in a place that you intimately know. It expresses an unsettling feeling that you can’t quite put your finger on. One that is softer than the presence of a ghost, and quieter than the click of a camera, but nonetheless sincerely felt.