Earlier this year, game designer Julien Eveillé entreated the 10,000 people who'd purchased his game, but did not play it...to actually play it. "I appreciate the support, but also: Do play it," he wrote.

I found this entreaty absolutely curious. Backlogs in media are not unusual, but they're usually reserved for things you don't own or haven't yet experienced. That so many people purchased media and couldn't be bothered to press start is strange. What's stranger is that never finishing games is, in fact, the norm. Only 10% of people who purchase games ever complete them. “There’s a bunch of games this month that are coming out,” one beleaguered father told the Washington Post. “I know I’m not going to be able to get to it until months from now.”

The behavior of collecting things without playing with them is entirely at odds with how I understand culture should work. As one astute Redditor responded to a novice

You don't start a collection of something. You end up with a collection of something after a long time of being into something, but purposely starting to collect something is just going about it entirely from the wrong end.

I'm hard-pressed to find a similar dynamic in media as the one I see in games.

On the one hand, who cares? A sale is a sale. Move on and don't complain. Eveille's request, though, points to something more profound. Playing, not owning, games is the point, yet I am also guilty of this behavior. I feel it in my bones, but why? In my many years of playing and thinking about games, I think the most important thing for games to reconcile is time.

Time is not on our side

In 2017, Reed Hastings, CEO of Netflix, made news with one of the shortest summaries of late-stage capitalism I've seen. In 2017, he told investors:

“You know, think about it, when you watch a show from Netflix and you get addicted to it, you stay up late at night. We’re competing with sleep, on the margin. And so, it’s a very large pool of time.”

Netflix has been clear-eyed that time is the most significant constraint on its business, so anything that competes for your attention is a threat. Hastings also astutely pointed to the popularity of games as a threat: “We compete with (and lose to) ‘Fortnite’ more than HBO,” he said. “There are thousands of competitors in this highly fragmented market vying to entertain consumers, and low barriers to entry for those great experiences.”

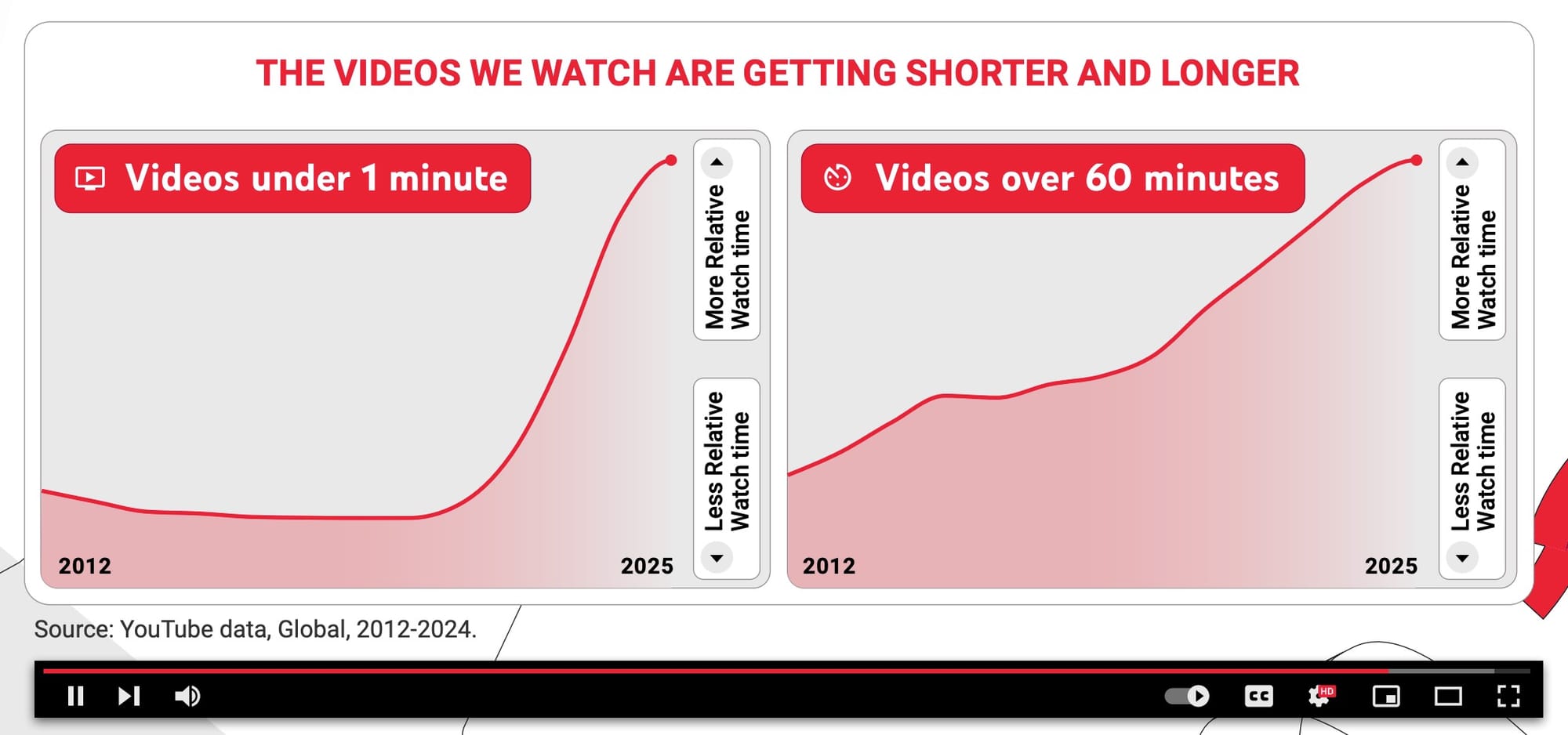

On the other end of the spectrum, YouTube has seen an increase in videos over 60 minutes and videos under 1 minute. This is in part due to the introduction of Instagram competitor YouTube Shorts. But it also reflects an understanding from creators that bite-sized experiences can be part of a healthy programming diet.

So if two of the biggest entertainment giants on the planet recognize the primacy of time, why are game makers moving in the opposite direction? This isn't a problem that's limited to enormous releases. Smaller, solo developer titles also consistently push experiences as long as games hundreds of times their size and budget.

There are myriad financial and strategic reasons why games are so long. Still, I'm less interested in the microtransactions/addiction side of the equation or why games are so long. I am, however, deeply concerned about games as cultural products and feel that an emphasis on length as meaningful consideration for games—big and small—works against their stature and the realization of "the ludic century."

A Brief History of Brevity

So how long is too long? There isn't a right answer to that question, but let's look at other media.

Most media roughly fall into the same bucket. A 400-page book takes about four hours. Music runs from a single song of just a couple of minutes to something closer to an hour. Theater is somewhere between an hour and a half and three hours. Movies are roughly two hours. Limited podcast series are a bit longer. The closest analogue to games' length is television. With The Sopranos, the rise of prestige TV over the last 30 years popularized the 13-hour-long season. We can question whether completing a series is the same as completing a season, so the run times could be 20-60 hours.

But even television has been contracting. According to Parrot Analytics, the average episode length of a network television season has dropped from 16.2 in 2018 to 11.8 as of July 2024, while the length of a streaming season in the same span has decreased from 10.7 episodes to 9.3.

The move towards shorter is not bad, and the overall history of media bends towards shorter length, but with wider distribution. For example, the short story emerged in the 19th century as a counter-balance to the three-volume novel favored by Victorians. The cheaper price and later serialization would open the door for authors from Chekhov to Borges and later writers like Alice Munro to enter their work into the canon with tighter and inventive work that could deliver profound impact in a shorter time. Alice Munro reflected:

I no longer feel attracted to the well-made novel. I want to write the story that will zero in and give you intense, but not connected, moments of experience. I guess that's the way I see life. People remake themselves bit by bit and do things they don't understand.

Munro has a sharp understanding that the story's length can reflect how our lives are actually lived–one chapter at a time.

Short stories are not alone. Poetry moved from epic to lyric, opening the door for individual emotional expression. Recorded music has gone through cycles, from the earliest classical performances to popular short singles through the 60s, and then back to concept records, and then returning to our recent run of TikTok hits. TV has also yo-yo'd, starting with 90-minute variety shows before settling into releasing half-hour episodes of sit-coms, before the binge-watching in the streaming era. Radio had long radio programs before declining in the television era and returning again with podcasts.

I could go on. There are many ways that games are different, exciting, and new. But to say that there is only one direction for the future games, and that is complete and total control over your attention? That worries me.

Surface area and pop culture

For many years, I had argued that games struggled with the "dinner table problem" and that people were scared to talk about games publicly. That has clearly changed, but a different problem has emerged.

The time commitment required for games creates a moat of experience and prevents players from sharing experiences with others. This is less a function of fragmented media and more a function of surface area. Movies, TV, and music are generally cheaper and shorter, so more people engage with them, good or bad. Other media also have the weight of history behind them. When games gate their access through an expensive PC or console, through length, through difficulty, through price, the number of people who can engage will be smaller, even if the total dollar amount is quite large.

Moreover, discourse about art creates a positive feedback loop between artists and their audience. The wider the surface area, the wider the range of opinions, the wider the cultural relevance. When games require months to complete, they struggle to create the simultaneous collective experiences that build cultural bonds.

Conversely, shorter games would enable the synchronized engagement patterns that transformed newspapers, television, and social media into culturally dominant forms. I say culturally dominant instead of economically dominant as a normative claim—perhaps secular trends will deliver games to the mountaintop. Still, I reserve judgment until a game designer is awarded a Guggenheim.

(As an aside, I am a fan of short cycles of games from a hand of Poker to run of Spelunky. These games privilege depth over length and allow for readings at any level of engagement in a way that longer, linearly constructed games do not.)

Canon Fodder

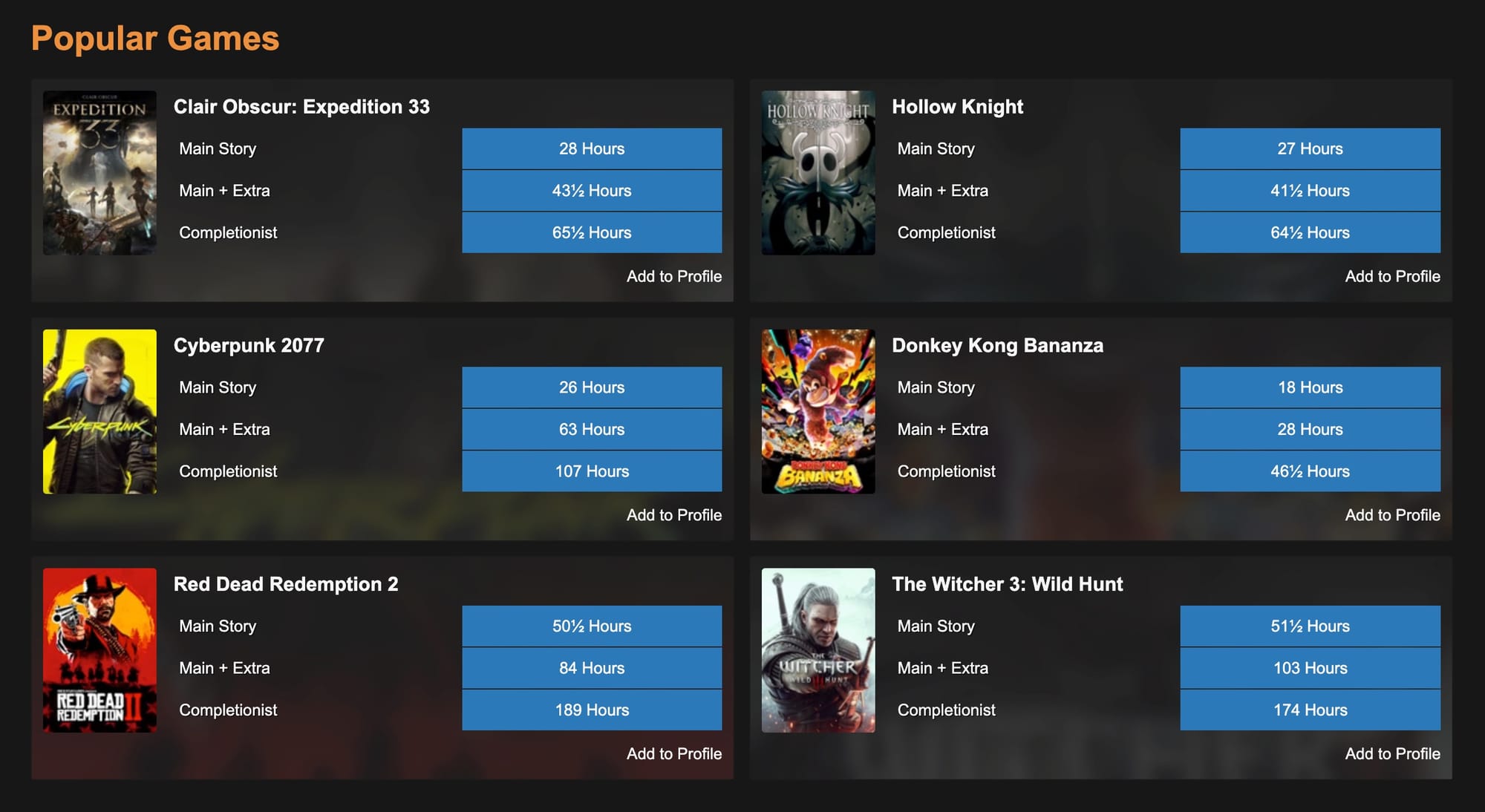

Longer games create challenges around establishing even a contested canon for the medium, simply by virtue of length. If we look at the AFI 100 or NPR's top 100 albums–hardly cultural vanguards–the time needed is modest, with 50 hours for the former and 25 for the latter.

For MetaCritic's top 100 games, you'd need at least 10 times as much time, at around 500 hours. The MetaCritic list mainly includes narrative games and doesn't track the myriad of online games that can require time to develop sufficient skill.

Remember that canons are the tip of the spear after whittling down dozens of candidates. When I submitted my top albums for the Village Voice's Pazz and Jop poll twenty years ago, I worked through the dozens of records down to my selects, and I wasn't even working full-time as a critic. Part of the reason that media that thrives on independent art forms works is an expectation that one's audience is looking for diversity in opinion. Choosing becomes a singular act, not part of the cultivation of broader taste.

Canons are important because they give us something to chew over, to respond to, and to argue about. "The process that winnows canonical texts from less enduringly valuable texts is not neutral or impartial, as some defenders of the canon assert," wrote English professor Paul Trout. "But highly contentious, involving the interplay of all kinds of forces--historical, antiquarian, economic, philosophical, demographic, aesthetic, cultural, political, etc." Trout's conclusions about diversifying the canon are deliberately obtuse, but one should at least complete the work to have a canon. Lengthy games make that impossible, ceding critical territory to people willing to engage with games and games alone.

But knowing what is terrible is also an important part of the process. Would you sit through 25 hours of Jason Statham's The Beekeeper? 30 hours of a middling record? Bad art provides a mirror, a counterpoint, and occasionally a cult following. But you can't form an opinion of something, even if negative, if it's too long.

The length of games forecloses many avenues that would help aid a deeper cultural literacy and criticism around games. Including them meaningfully in class curricula is impossible, even if their subjects would be helpful. In an arts context, given that a guest only spends 2-3 hours in a museum, long games are incompatible with institutional adoption. When I helped program the games for the permanent collection for MoMA, the exhibition constraints for games proved challenging. While games like Tetris and Canabalt work well for short play times, longer titles like Super Mario 64 cannot be experienced the way that other objects in the design collection could.

Moral Formation

Over the years, as life progresses, your thinking and relationship to media change. Your interests and your partner's diverge (in healthy ways!). She winds down watching Top Chef, and you vacillate between the Sight and Sound 200 and Adult Swim. You have a daughter, and her interests are entirely her own. While children's media thankfully converges more seamlessly these days with your own interests, at no point do you forget that you are watching a family of talking Irish puffins or Australian dogs.

And so the decision to pick and maintain media interest takes on a ruthless quality. You abandon shows that have overstayed their welcome, lost their bite, or fumbled the plot. You turn to lists and canons to help sharpen your taste against an onslaught of releases. You listen to the media about The Thing without engaging The Thing directly. This is part of getting older. Someday, you can ask the robot nurse to strap you to the VR headset, press play on your backlog, strap you into a Waymo autonomous rocket, and shuttle you into the sun.

That games ask for so much of our time takes on a moral component. It is an exclusive pursuit in that it helps shape who we are. Blessedly, games allow us to build relationships with others through cooperation or competition, but they ask for our attention. That means other things must take a back seat.

Years ago, I raised an honest concern that the investment in gaming was making it more like a country club with green fees and high-priced equipment. Since then, there's been an explosion of free games that ask for time commitments instead. Pierre Bourdieu would call this time requirement a mechanism of class distinction—temporal barriers that exclude working-class participants from cultural literacy. This transforms gaming from a potential democratic art form into another site of cultural reproduction where leisure time becomes a prerequisite for participation.

At yet, when it comes to games, nothing–not the age of game makers, not the introduction of new technologies, not widely available game guides–has changed gaming's relationship to time. If anything, with the introduction of forever games-as-a-service like Fortnite, the motivation has been to dominate more and more of your waking hours. While big titles like Call of Duty and other shooters have shortened their single-player campaigns, the goal and business model is to keep you engaged for as long as possible.

But on a simpler level, it's simply too much to ask us to devote our lives to play at the expense of life's myriad experiences. That delta between becoming well-played vs. well-read, well-watched, and well-listened is simply unjust.

So what is the perfect length?

So, how long should games be? That's the wrong question.

Durational work like Christian Marclay's 24-hour film and the 1,000 year composition of Longplayer can blissfully sit alongside Hossein Molayemi and Shirin Sohani's 20-minute award winning short and Napalm Death's two-second "You Suffer."possible

In "The Philosophy of Composition" (1846), Edgar Allen Poe argued that any work "too long to be read at one sitting" must "dispense with the significant effect derivable from unity of impression," because "the affairs of the world interfere, and everything like totality is at once destroyed." Poe's argument isn't just that working too long at one time is inconvenient. He argues–using "The Raven" as his exemplar–that a single session is a requirement for great poetry. Breaking the spell a poet casts ruins the transformative power of the medium.

I have felt this to be true practically with games whenever I forget something complex's control scheme. Part of the rationale for games as "easy to learn, difficult to master" is that one can simply sit down and play without referring to a manual. More importantly, some of my favorite games–Inside, Firewatch, In the Pause Between Ringing–have lulled me into a complete trance as the evening drifts late through my window.

One place that excites me is artists building games with an exhibition context in mind. Artists like Alice Bucknell, Danielle Brathwaite-Shirley, Vinny Roca, Jakob Steensen, Leo Castañeda, and others are approaching games as a complete experience with the constraints of the gallery in mind. That emphasis on completeness merged with brevity opens the door for a whole work in the same way that a 19th-century filmmaker could only have imagined a seven-second video.

We face a choice. Are we players engaging in a medium of great importance? Are we obsessives who push everyone and everything a way in the service of our backlog? Or are we collectors hoarding, but never truly finishing? I love playing games, so hopefully, we can finish more of them together.